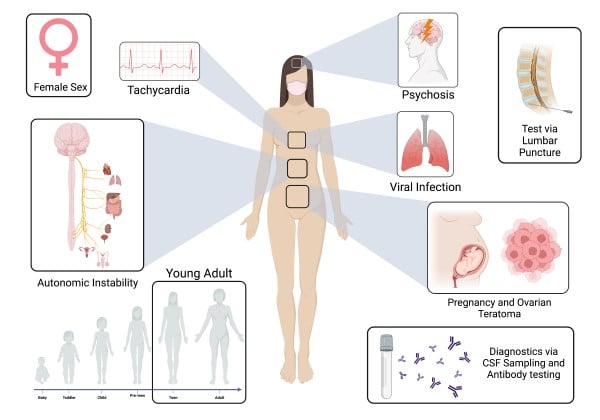

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis (ANMDARE) is a type of autoimmune encephalitis that preferentially affects young women of reproductive age and is strongly associated with viral infections and ovarian teratomas.

Here, we present a case of a 20-year-old patient with autoimmune encephalitis in the setting of an ovarian teratoma, complicated by pregnancy.

The patient, with no significant past medical history, was brought in by her parents due to acute onset of significant behavioral changes. Initial workup revealed a positive live intrauterine pregnancy of 14 weeks and a right 2.5 cm ovarian cyst. After consulting with psychiatry, the patient was placed on an involuntary behavioral health hold but became too agitated to be transferred safely to an inpatient psychiatric unit. Ultimately, she was admitted to inpatient service for acute psychosis with concern for an organic etiology. Further investigation of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid revealed pleocytosis and NMDAR antibodies. Obstetrics was consulted for possible ovarian teratoma as a source of the NMDAR antibodies. After consultation with the patient’s parents and the ethics board, a right salpingo-oophorectomy and medical termination of pregnancy was performed uneventfully. Pathology results confirmed a cystic teratoma. The patient’s symptoms gradually improved, and the patient was eventually discharged home.

Emergency physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for ANMDARE when evaluating young female patients with an acute onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms. It is our duty as emergency physicians to rule out organic etiologies of psychiatric presentations. Screening should be done to investigate potential sources of ectopic antibody production, including ovarian teratomas. Pregnancy warrants a detailed conversation with the patient or guardian and a medical ethics board to ensure the safety of the patient and fetus. Early treatment is associated with good patient outcomes.

Introduction

Autoimmune encephalitis, also known as antibody-mediated encephalitides, is a collection of neurological disorders, first described in 2007, caused by antibodies attacking self-antigens in a patient’s central nervous system (CNS).1,2The most common type of autoimmune encephalitis is ANMDARE, which preferentially affects children and young women and is strongly associated with viral infection and ovarian teratomas.3 Mortality rates are estimated between 8% and 10%.2 In patients presenting with neuropsychiatric symptoms refractory to typical antipsychotics or multi-regimen therapies, as well as those with abnormal vital signs, an organic etiology must be considered in the differential before placing a psychiatric diagnosis on the patient.

Case Description

A 20-year-old female with no significant past medical history was brought into the ED by her parents for various behavioral changes. Per the patient’s mother, her behavioral changes included auditory and visual hallucinations, and seeing and conversing with deceased family members. The patient was sexually inappropriate with other family members and her pets. She also threatened to kill herself in multiple ways. Notably, she was unable to interact with others in a meaningful way, making bizarre statements such as “you’re trying to eat me,” and could not answer questions coherently. These symptoms were ongoing for a few weeks leading up to ED presentation, with no precipitating triggers. There was no known psychiatric history in the family. No illicit drug abuse was noted. The patient was previously evaluated by two outside facilities prior to this ED visit. Those evaluations included unremarkable laboratory studies and a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the head without contrast; the patient was discharged home with outpatient follow-up after she denied symptoms.

Upon initial diagnostic evaluation, the complete blood count and chemistry panel were unremarkable. The patient’s urine drug screen was negative for any tested substances. Thyroid stimulating hormone was within normal limits. However, her serum qualitative human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) came back positive, prompting further investigation. Quantitative hCG was at 111,358 mIU/mL. As a result, an obstetric ultrasound was obtained, which revealed a single live intrauterine pregnancy with a sonographic date of 14 weeks. There was also a right-sided 2.5 cm ovarian cyst with a solid mural component at the base.

Psychiatry was consulted given her symptoms and requested further investigation for medical causes due to acute onset and her young age. Neurology was then consulted and felt that the patient’s symptoms were more psychiatric in etiology, given the absence of any focal neurological findings and seizures. However, neurology also stated that the patient’s case could warrant further neurologic work-up if she did not improve. As a result, psychiatry then placed the patient on an involuntary behavioral health hold for acute psychosis causing danger to herself and grave disability. The patient, while awaiting placement over the next two days, became increasingly agitated, verbally abusing and spitting at staff, unable to answer questions appropriately, and requiring intermittent sedatives and restraints. This escalated to scheduled benzodiazepines, but the patient still had no improvement and therefore could not be transferred to an inpatient psychiatric facility due to worsening rhabdomyolysis from fighting the restraints. Vital signs fluctuated throughout her ED stay, with intermittent tachycardia and hypertension. Ultimately, the patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for further work-up.

The patient’s antinuclear antibodies (ANA) panel, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis panel, ceruloplasmin, methylmalonic acid, and iron studies were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cervical/thoracic/lumbar spine were negative for any acute abnormalities. The meningitis panel was negative for any infectious culprit. However, cerebrospinal fluid studies were significant for pleocytosis concerning for an inflammatory process. Cultures had negative growth for 72 hours. Neurology was re-consulted due to this abnormal finding that could be due to autoimmune encephalitis versus paraneoplastic syndrome and agreed to transfer the patient to their service.

Several days later, specialized send-out tests of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid came back positive for N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibodies. She was started on five days of intravenous immunoglobulin with methylprednisolone and one day of rituximab. MRIs of the abdomen and pelvis were ordered to evaluate for any known tumors to be attributed to her NMDAR antibodies. However, they only re-demonstrated the known right ovarian cyst. CT of the chest with contrast revealed no lesions or tumors as well. With no clear source and failure to improve on medical management, obstetrics was consulted to evaluate the ovarian cyst for a possible teratoma, as the first ultrasound read it as having a solid mural component at the base. After a meeting with the patient’s parents and the ethics committee, a decision was made to proceed with a right salpingo-oophorectomy and abortion for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, as pregnancy was also known to precipitate or worsen autoimmune encephalitis. The patient had an uncomplicated operation, and the pathology results were positive for a cystic teratoma. Her encephalopathy gradually improved over the next several days, and she was discharged home.

Etiology and Presentation

The most common type of autoimmune encephalitis is ANMDARE, which is caused by antibodies against the NR1 subunit of the anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and most commonly affects women of reproductive age.1,4,5 Up to 58% of all women with ANMDARE also have an underlying teratoma, with bilateral teratomas occurring in up to 15% of patients.2,5 In addition to teratomas, both viral infections and herpes simplex encephalitis are known triggers of ANMDARE.6

Characterized by neuropsychiatric symptoms, ANMDARE most commonly presents with behavioral changes, seizures, and cognitive impairment.1,2 Autonomic instability — such as excess salivation, hyperthermia, variations in blood pressure, tachycardia, and hypoventilation — is also commonly seen. Prior case studies have suggested that seizure patients with ANMDARE may be more susceptible to cardiac dysrhythmias as compared to patients presenting with seizures due to other etiologies.4 One retrospective study of 100 patients found cardiac dysrhythmias to occur in up to one-third of patients.7 Notably, the present case describes a patient who presented with primarily psychiatric symptoms without extra-psychiatric manifestations as described in prior case reports.5,8

The origin of the autoantibodies featured in ANMDARE is largely variable, with both pregnancy and ovarian teratomas being well-documented sources of immunogenic modulation and potential triggers of antigenic presentation of NMDA receptor subunits.3,8 Without treatment, ANMDARE can be fatal. Therefore, early diagnosis through thorough history-taking and clinical workup is crucial in improving patient outcomes. Prompt excision of the ovarian tumor, or any ectopic source of autoantibodies, is associated with improved outcomes.3

Clinical Diagnosis

In most cases, typical neurologic workup of neuropsychiatric symptoms includes magnetic resonance imaging, which is generally normal or shows only mild abnormalities in the setting of ANMDARE. A diagnosis of ANMDARE can be confirmed however, through careful examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for evidence of autoantibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the NMDA receptor, lymphocytic pleocytosis, and levels of proteases and anti-proteases.1,2,9

Astute physicians may arrive at the correct diagnosis, as demonstrated in the case by Ito et al where — despite only mildly elevated CRP levels and CSF pleocytosis, negative abdominal ultrasound examination and MRI showing no ovarian teratoma — physicians diagnosed a case of ANMDARE in a 19-year-old pregnant patient.8 Another case report by Reisz et al describes a unique instance of a 31-year-old pregnant patient with severe hypokalemia as a manifestation of ANMDARE.10 In our case, a strong index of suspicion with the patient’s inability to improve on psychiatric medications and overall unremarkable blood work worked in tandem to point toward testing for anti-NMDAR antibodies.

Treatment and Outcomes

Treatment of ANMDARE surrounds immunomodulation using glucocorticoids and intravenous immunoglobulins as first-line therapy, with rituximab and cyclophosphamide reserved for treatment in refractory cases.1,2 Symptomatic treatment of associated clinical symptoms is also indicated, including phenobarbital or phenytoin for seizures.

Factors that indicate poor prognosis include ICU admission, treatment delay >4 weeks, lack of clinical improvement within 4 weeks, and an abnormal MRI.11 Mortality rates range from 8% to 10%.2 Most patients have favorable long-term outcomes but still warrant follow-ups periodically to assess for recurrence, with 12% to 24% of patients experiencing them within the first 24 months.12

A study by Patel et al. investigated the cardiac manifestations of ANMDARE, specifically those resulting from ANMDARE-induced sinus node dysfunction such as sinus arrest, sinus bradycardia, and inappropriate sinus tachycardia.5

ANMDARE in Pregnancy

A retrospective study and literature review by Joubert et al analyzed the associations between ANMDARE and pregnancy and found that ANMDARE in the setting of pregnancy is associated with high rates of obstetric complications.11 Investigating 27 cases, Joubert et al reported medical termination of two pregnancies, spontaneous miscarriage in two pregnancies, maternal death prior to delivery in one case, and uneventful delivery in 22 cases.13 An ovarian teratoma was found and removed in four patients. It is postulated that transplacental transfer of NMDAR antibodies during gestation can result in neurologic deficits in the newborn.13 Due to our patient’s severe psychosis, a decision was made with the patient’s parents and the ethics committee to terminate the pregnancy due to concerns about its role in worsening the patient’s encephalitis.14

Conclusion

This case report highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the emergent care of ANMDARE, with consideration from neurology, psychology, and obstetrics. Emergency physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for ANMDARE when evaluating young female patients with an acute onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms and worsening conditions despite antipsychotic medications and interventions. Screening should be done to investigate potential sources of ectopic antibody production, including ovarian teratomas. Pregnancy warrants a detailed conversation with the patient and/or guardian and a medical ethics board to ensure the safety of the patient and fetus. Early treatment is associated with good outcomes.

Take-Home Points

- Clinicians should maintain a high degree of suspicion for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis (ANMDARE) and ovarian teratomas in young female patients presenting acutely with psychiatric symptoms, autonomic manifestations, and worsening conditions despite antipsychotic medications and interventions.

- Early diagnosis is critical in improving patient outcomes in pregnancy-associated ANMDARE.

- A multidisciplinary approach is crucial in the appropriate, comprehensive management of ANMDARE.

References

- Yang M, Lian Y. Clinical features and early recognition of 242 cases of autoimmune encephalitis. Frontiers in Neurology. 2022;12. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.803752

- Dalmau J, Graus F. Antibody-mediated encephalitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(9):840-851. doi:10.1056/nejmra1708712

- Gu J, Chen Q, Gu H, Duan R. Research progress in teratoma-associated anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: The gynecological perspective. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2021;47(11):3749-3757. doi:10.1111/jog.14984

- Ziaeian B, Shamsa K. Dazed, confused, and Asystolic: Possible signs of anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2015;42(2):175-177. doi:10.14503/thij-13-3987

- H. Patel K, Chowdhury Y, Shetty M, et al. Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis related sinus node dysfunction and the lock-step phenomenon. American Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2020;8(12):503-507. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-8-12-20

- Dalmau J, Armangué T, Planagumà J, et al. An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: Mechanisms and Models. The Lancet Neurology. 2019;18(11):1045-1057. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30244-3

- Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: Case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. The Lancet Neurology. 2008;7(12):1091-1098. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(08)70224-2

- Ito Y, Abe T, Tomioka R, Komori T, Araki N. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis during pregnancy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2010;50(2):103-7. Japanese. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.50.103. PMID: 20196492.

- Räuber S, Schroeter CB, Strippel C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid proteomics indicates immune dysregulation and neuronal dysfunction in antibody associated autoimmune encephalitis. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2023;135:102985. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102985

- Reisz D, Gramescu I-G, Mihaicuta S, Popescu FG, Georgescu D. NMDA autoimmune encephalitis and severe persistent hypokalemia in a pregnant woman. Brain Sciences. 2022;12(2):221. doi:10.3390/brainsci12020221

- Balu R, McCracken L, Lancaster E, Graus F, Dalmau J, Titulaer MJ. A score that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology. 2019 Jan 15;92(3):e244-e252. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006783. Epub 2018 Dec 21. PMID: 30578370; PMCID: PMC6340387.

- Barry H, Byrne S, Barrett E, Murphy KC, Cotter DR. Anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis: review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. BJPsych Bull. 2015 Feb;39(1):19-23. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.113.045518. PMID: 26191419; PMCID: PMC4495821.

- Joubert B, García-Serra A, Planagumà J, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology - Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation. 2020;7(3). doi:10.1212/nxi.0000000000000668

- Cortese R, Mariotto S, Mancinelli CR, Tortorella C. Pregnancy and antibody-mediated CNS disorders: What do we know and what should we know? Frontiers in Neurology. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.1048502