Acute non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome is a rare condition not frequently reported in the literature.

We report on a 44-year-old male who presented to the ED with bilateral lower extremity compartment syndrome likely secondary to cocaine-induced rhabdomyolysis. The patient required bilateral four-compartment fasciotomy, ICU admission, and temporary hemodialysis. Ultimately, his cocaine usage was the only identifiable etiology of his presentation. Although substance-induced rhabdomyolysis has been widely reported, the progression to compartment syndrome is not frequently encountered and usually of multifactorial etiology. Rapid recognition of this uncommon condition is important as urgent fasciotomy is the mainstay treatment.

Introduction

We present a case of compartment syndrome likely due to substance-induced rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis due to substance use, especially cocaine, is a well-documented occurrence.1,2 Additionally, non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis, usually due to strenuous exercise, has been reported as a rare cause of compartment syndrome without significant trauma.3,4 However, compartment syndrome due to cocaine-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare or underreported. Ikponmwosa, et al. described a case of substance abuse-associated compartment syndrome secondary to intravenous injection of cocaine and heroin. However, this patient only developed isolated anterior upper extremity compartment syndrome near the injection site.5 Additionally, Huson and Fontenot reported a case of non-traumatic compartment syndrome associated with cocaine use, but they ultimately suspected multiple contributing factors including prolonged creatine usage and strenuous exercise.6 While there have been many reported cases of cocaine abuse resulting in rhabdomyolysis, our paper identifies a further complication of compartment syndrome that is not frequently encountered.

Case

A 44-year-old male with a past medical history of polysubstance abuse presented to the ED by EMS transport with bilateral lower extremity pain. He reported severe pain in both extremities that was worse in the lower legs. He had associated swelling of both legs and was unable to walk due to the pain. He denied any trauma. Reports waking up with these symptoms and denied any pain or symptoms before falling asleep. Denied tongue biting or bladder incontinence. He endorsed a history of IV drug use but states he had not used any in a few months. Of note, he was recently released from jail and had bilateral ankle bracelets – one for house arrest and one for continuous alcohol monitoring.

His triage vital signs were HR 89 bpm, RR 18 rpm, BP 130/100 mmHg and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. On initial evaluation, he was very uncomfortable appearing. He had cold, blue, and mottled-appearing lower extremities with edema that extended to the mid-thigh bilaterally. He had diffuse tenderness of the lower leg, the skin was very tight, and he had worsening pain with passive flexion. His ankle bracelets were loose and not constricting his legs. Dorsalis pedis (DP) and posterior tibial (PT) pulses were not palpable nor able to be auscultated with portable doppler, however, both arteries were easily visualized with pulsatile flow on bedside ultrasound.

Initial differential diagnosis included arterial thrombus, congestive heart failure, deep venous thrombosis, proximal venous obstruction, and compartment syndrome. CBC was remarkable for an elevated white blood cell count of 17 K/dL. BMP was remarkable for an acute kidney injury with a BUN of 29 mg/dL and Cr of 1.9 mg/dL as well as hyperkalemia of 6.8 mmol/L. His CPK was 86,030 u/L and lactic acid was 1.9 mmol/L. Urinalysis showed large urine blood with 0-2 RBC/hpf and the urine drug screen resulted positive for benzodiazepines and cocaine. His EKG did not show any hyperkalemic changes. Fluid resuscitation was started, and his hyperkalemia was treated with calcium, insulin, and albuterol. Formal ultrasounds of the bilateral lower extremities were ordered with venous duplex and ankle-brachial index (ABI). This showed normal ABI bilaterally, no evidence of DVT, however, hemodynamics did suggest increased central venous pressure.

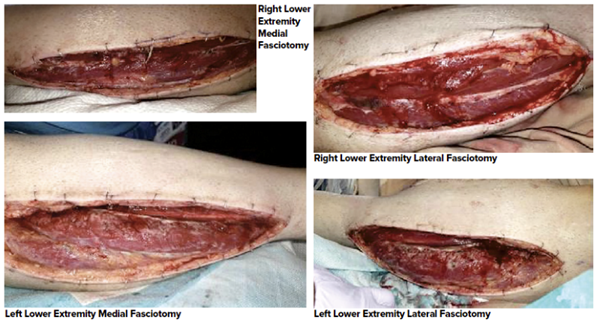

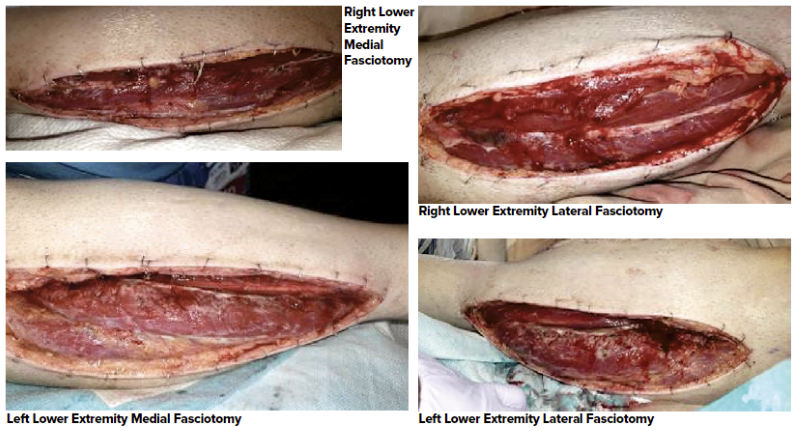

On re-evaluation, the overall discoloration of his legs had improved but he was still having significant pain despite multiple rounds of narcotic pain medications. Based on the increased central venous pressure noted on venous studies, a contrast CT of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained to rule out proximal obstruction which was unremarkable. At that time, the patient continued to have uncontrolled pain with edema below the knees bilaterally, and diffusely tight compartments. Orthopedic and vascular surgery were consulted due to concern for compartment syndrome. His ankle bracelets were removed prophylactically. Plain radiographs of bilateral tibia/fibula, as requested by orthopedics, did not show osseous abnormalities. Repeat BMP showed worsening renal function with BUN of 34 mg/dL and Cr of 2.6 mg/dL and increased CPK to 125,50 u/L. After evaluation by vascular surgery, he was taken urgently to the OR for a four-compartment fasciotomy. The intraoperative findings were notable for “tense right calf compartments with significant muscle swelling and edema in all compartments, without evidence of infection or muscle necrosis; left compartment tense with the majority of muscle swelling and edema in the anterior compartment.” Photos were taken post-fasciotomy, see images 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Post-operatively, he was admitted to the ICU. His hospitalization was complicated by worsening renal failure and oliguria with a peak BUN of 42 mg/dL and Cr of 6.7 mg/dL ultimately requiring temporary hemodialysis. With continued supportive care, his CPK gradually improved and his renal function recovered. His leg wounds were ultimately closed 12 days after his initial procedure. He was discharged to a rehabilitation facility 19 days after admission with a final diagnosis of bilateral lower extremity compartment syndrome from cocaine-induced rhabdomyolysis.

Discussion

This was a case of suspected cocaine-induced non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis with resulting compartment syndrome requiring fasciotomy. The pathophysiology of rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome is interrelated and begins with an insult to the muscle cells. In rhabdomyolysis, the initial insult either directly damages the myocytes or reduces the availability of ATP or oxygen. This leads to an alteration in ion influx that disrupts the intracellular space and sets off a cascade of events that result in muscle cell necrosis and the release of contents into the bloodstream. The myocytes release creatine kinase (CK) and myoglobin, the latter of which is directly nephrotoxic and is the primary cause of the acute renal failure that is seen in up to 33% of cases. The diagnosis is typically established by a marked elevation in CK (typically > 5x the upper limit of normal) or by the appearance of myoglobin in the urine.2 Meanwhile, compartment syndrome is most commonly caused by direct trauma with 75% of cases associated with a long bone fracture.7 The resulting muscle damage and edema in the non-compliant muscle fascia leads to an increase in compartmental pressure that can collapses the arterioles and compromises perfusion. Muscle ischemia results which further compounds the damage and may lead to worsening CK elevation and rhabdomyolysis in the post-injury period.

The link between traumatic compartment syndrome and resulting rhabdomyolysis is well-established.2,7,8 However, as in this case, non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis can also result in compartment syndrome through a cascade of muscle ischemia and fluid sequestration that causes an increase in compartment pressures. There is a wide range of causes leading to the development of atraumatic rhabdomyolysis including strenuous exercise, drugs, medications, malignant hyperthermia, genetic diseases, infections, and more. Additionally, non-traumatic compartment syndrome can occur in the absence of underlying rhabdomyolysis. This is a rare diagnosis with a wide variety of underlying etiologies including diabetes, hypothyroidism, autoimmune, DVT, and leukemia.9,10 It can even occur chronically with reversible ischemia usually caused by exertion in repetitive exercise.8 The anterior compartment of the lower leg is the most involved site,7 but it can occur anywhere even in the absence of direct trauma.

The development of rhabdomyolysis from cocaine is multifactorial due to increased sympathomimetic activity, muscle hyperactivity, hyperthermia, and arterial vasoconstriction that leads to muscle ischemia. It can develop with all routes of use but is more commonly seen with IV use or smoking crack cocaine due to higher blood levels of the drug.11 There are a few case reports of compartment syndrome secondary to rhabdomyolysis with cocaine use, but these cases are frequently multifactorial in etiology. As mentioned previously, Ikponmwosa et al reported a case of compartment syndrome that developed near the site of injection with heroin and cocaine.5 The development of compartment syndrome was likely due to the direct trauma of needle injection in addition to polysubstance usage. In contrast, our patient only endorsed intranasal cocaine usage. Furthermore, the bilateral presentation makes any direct trauma less likely as an underlying factor. Riolo et al also identified a case of rhabdomyolysis associated with crack cocaine usage and subsequent compartment syndrome. This patient's rhabdomyolysis led to over resuscitation and four-limb compartment syndrome.12 However, given the timeline of events, it was likely not the crack cocaine abuse but rather the high volume of fluids given to treat rhabdomyolysis that led to compartment syndrome. Srivilasa, et al. report a similar case of cocaine-associated compartment syndrome requiring bilateral fasciotomies but their patient was suspected to have overdosed on olanzapine as well. Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic that has been reported as a rare cause of rhabdomyolysis.13 The combination of cocaine use with other potential muscle-damaging drugs should be considered when evaluating patients with non-traumatic muscle pain. Lastly, in a case series presented by Levine, et al., they identified three patients who presented with compartment syndrome after rhabdomyolysis associated with "bath salt" use.14 This included paraspinal and bilateral forearm compartment syndrome, of which two patients required fasciotomy. "Bath salts" are synthetic cathinones that also act as sympathomimetics and it is reasonable to assume that any substance with sympathomimetic activity could potentially present with these complications.

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome is generally considered clinical, with severe pain as the most consistent clinical sign. Additionally, pain with passive stretching is frequently mentioned in the literature as a classic feature.7,8 Symptoms such as paralysis and pulselessness are considered late findings and their absence should not make the diagnosis less likely. Compartment pressures can be measured with commercial products however their utility remains controversial and they are not frequently used at our institution.

The treatment of rhabdomyolysis is primarily supportive and includes identifying the cause, fluid resuscitation, correcting electrolyte abnormalities, and managing the downstream consequences such as renal failure.1 In contrast, the treatment of compartment syndrome focuses on early identification, surgical consultation, and fasciotomy.3,6,8,13,15 As highlighted by Riolo, et al, aggressive fluid resuscitation in rhabdomyolysis can worsen compartment pressures and has been identified as an inciting factor in cases of nontraumatic compartment syndrome.12 After six hours of ischemia, tissue necrosis starts to occur and can lead to permanent muscle and nerve damage. Meanwhile, if treated with fasciotomy within six hours, then complete recovery of limb function is anticipated.8 This highlights the necessity of vigilance on the part of the diagnosing provider as well as the prompt involvement of our specialist colleagues.

Conclusion

Non-traumatic compartment syndrome is a rare diagnosis that requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the evaluating clinician. Likewise, primary rhabdomyolysis has been identified as one cause of this atypical presentation. Meanwhile, cocaine usage is frequently reported as one of many etiologies causing rhabdomyolysis. To our knowledge, there are no reported cases where cocaine use was thought to be the only underlying etiology of rhabdomyolysis and subsequent compartment syndrome. This case helps to understand the underlying pathophysiology, raises awareness of the progression, and for similar causes of this rare presentation. Urgent recognition remains critical as the definitive treatment is surgical fasciotomy.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Compartment syndrome is a rare complication of substance-induced rhabdomyolysis.

- Treatment of rhabdomyolysis and related electrolyte abnormalities is supportive medical management

- In contrast, the treatment of compartment syndrome is emergent surgical fasciotomy therefore a high index of suspicion for this complication needs to be maintained.

References

- Roth D, Alarcón FJ, Fernandez JA, Preston RA, Bourgoignie JJ. Acute rhabdomyolysis associated with cocaine intoxication. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(11):673-677. doi:10.1056/NEJM198809153191103

- Torres PA, Helmstetter JA, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Rhabdomyolysis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):58-69.

- Brinley A, Chakravarthy B, Kiester D, Hoonpongsimanont W, McCoy CE, Lotfipour S. Compartment Syndrome with Rhabdomyolysis in a Marathon Runner. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2018;2(3):197-199. Published 2018 Jun 12. doi:10.5811/cpcem.2018.4.37957

- McKinney B, Gaunder C, Schumer R. Acute Exertional Compartment Syndrome with Rhabdomyolysis: Case Report and Review of Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:145-149. Published 2018 Feb 8. doi:10.12659/ajcr.907304

- Ikponmwosa A, Bhasin N, Dellagrammaticas D, Shaw D, Scott D. Upper Arm Compartment Syndrome Secondary to Intramuscular Cocaine and Heroin Injection. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2007;33(2):254. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.09.014

- Huson H, Fontenot T. Idiopathic spontaneous bilateral leg compartment syndrome in a 43-year-old male. Surg Case Rep. 2018;2(1):21-23.

- Torlincasi AM, Lopez RA, Waseem M. Acute Compartment Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; December 7, 2020.

- Kiel J, Kaiser K. Tibial Anterior Compartment Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; January 2020.

- Mahdi H, Gough S, Gill KK, Mahon B. Acute spontaneous compartment syndrome in recent onset type 1 diabetes. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(7):507-508. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.046425

- Veeragandham RS, Paz IB, Nadeemanee A. Compartment syndrome of the leg secondary to leukemic infiltration: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1994;55(3):198-201. doi:10.1002/jso.2930550314

- Selvaraj V, Gollamudi LR, Sharma A, Madabushi J. A case of cocaine-induced myopathy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(3):PCC.12l01451. doi:10.4088/PCC.12l01451

- Riolo MD, G., Arora MD, D., Taylor MD, D., & Wood MBChB, FRCS, G. C. (2016). Spontaneous Four Limb Compartment Syndrome. Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.22374/cjgim.v10i4.90

- Srivilasa, Charlie & Shupp, Jeffrey & Shiflett, Anthony. (2014). Compartment Syndrome of the Leg Requiring Emergent Fasciotomy Resulting from Multi-Drug Overdose. Surgical Science. 05. 39-42. 10.4236/ss.2014.52009.

- Levine, M., Levitan, R., & Skolnik, A. (2013). Compartment syndrome after "bath salts" use: a case series. Annals of emergency medicine, 61(4), 480–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.11.021

- Khan T, Lee GH, Alvand A, Mahaluxmivala JS. Spontaneous bilateral compartment syndrome of the legs: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3(6):209-211. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.02.003