Bell's palsy, also called idiopathic facial nerve palsy, is the paralysis of facial motor function without an identifiable cause.

It typically presents with sudden onset unilateral facial paralysis and may be associated with ipsilateral hyperacusis, decreased taste, and decreased lacrimation.1 It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and the emergency physician should thoroughly investigate other more serious etiologies, such as cerebral vascular accident (CVA).

Introduction

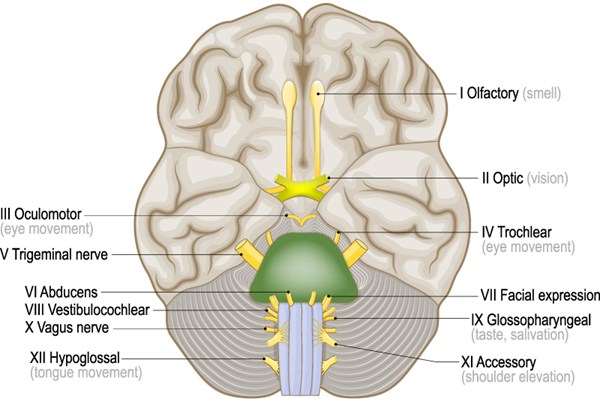

Unilateral facial paralysis is differentiated by whether it is forehead-sparing (an upper motor neuron lesion) or non-forehead-sparing (a lower motor neuron lesion). This distinction prompts investigation into intracranial versus extracranial etiologies. Facial nerve paralysis that is associated with other signs or symptoms (such as headache, fever, other cranial nerve involvement, extremity weakness, etc.) further complicates this distinction and broadens the differential. We present the case of a 13-year-old female with MRI confirmed Bell’s palsy (facial; facial paralysis) with associated involvement of cranial nerves 5 (trigeminal; decreased sensation), 9/10 (glossopharyngeal/vagus; difficulty swallowing), and 12 (hypoglossal; tongue deviation).

Case

A 13-year-old African-American female presented to the emergency department with one week of worsening left-sided facial paralysis. It began with slight asymmetry when smiling but eventually progressed to difficulty holding liquids in her mouth and dysphagia. She denied odynophagia. She also reported blurry vision and retrobulbar pain when looking straight ahead. Additionally, 2 days before presentation she developed pain over her left zygoma that radiated to above her left ear.

The patient was otherwise healthy; she had no past medical history, did not take daily medications, had no known drug or environmental allergies, and was up to date on her vaccinations. She lived with her mother and brother in an urban environment. She denied recent illness, travel, trauma, or insect or tick bites. She could not identify a precipitating event or new exposure. Family history was noncontributory and negative for any diseases that could increase her risk of stroke, such as Sickle Cell disease or clotting disorders.

On physical examination, vital signs were within normal limits. She had a down-turned smile on the left, inability to raise her left eyebrow, and inability to fully close her left eye. She spoke out of the right side of her mouth while her left side pulled toward midline. She had decreased sensation over her left forehead, temple, maxilla, and mandible. Her tongue and her uvula deviated to the left. Hearing was grossly symmetrical. Extraocular movements were intact without pain and she did not have nystagmus. Visual fields and acuity were intact. The Romberg test was negative, and pronator drift was absent. Strength was intact throughout. Gait was normal. All other systems were unremarkable and age appropriate. Head CT demonstrated scattered punctate parenchymal calcifications that were of undetermined etiology or significance. This was further evaluated with MRI, which identified enhancement of the left facial nerve and re-demonstrated the calcifications, noting no associated signal abnormalities that would raise concern for clinically significant pathology. CBC and CMP were within normal limits and the pregnancy test was negative. In conjunction with neurology consultation, the patient was discharged with an eye shield, eye lubricant, and instructions to follow up with neurology.

Discussion

It is classically taught that Bell's palsy is an isolated facial nerve paralysis that lacks an identifiable cause and is not associated with other cranial nerve deficits. However, there are reports of other cranial neuropathies associated with facial nerve paralysis, though this is uncommon.2,4,5,6 One prospective study found that of 51 patients with Bell's palsy, and 15 had at least one other associated cranial nerve palsy: ipsilateral sensory deficit (17 cases), contralateral sensory deficit (1 case), ipsilateral tongue weakness (1 case), decreased gag reflex due to palatal sensory deficit (2 cases).2

Because of the rarity of associated cranial nerve palsies, it is imperative that serious diagnoses be excluded prior to making the diagnosis of Bell's palsy. In particular, a CT and/or MRI must be included to evaluate for cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Imaging should also be obtained if facial twitches or spasms preceded paralysis, as this may indicate a tumor compressing the facial nerve.1 If other symptoms are prominent or certain risk factors are present, the workup should be expanded. According to one study of adult patients, emergency physicians have low rates of misdiagnosing Bell's palsy (0.8%); the most common incorrect diagnoses are CVA, herpes zoster, Guillain-Barre, and otitis media.7

Once Bell's palsy has been diagnosed, severity and prognosis can be determined using the House-Brackmann or Stony Brook facial grading systems. However, these tools are infrequently utilized in the emergency department and therefore not discussed further here.8 Neurology consult in the ED may be appropriate. Indeed, neurology was consulted in the management of this case. Additional consults or follow-up with ophthalmology or ENT should be considered if there is severe eye or throat involvement, respectively, or if symptoms persist beyond 4 weeks.3

Complete resolution of symptoms can be expected, and approximately 70% of cases resolve spontaneously.3 Although there are conflicting reports, nerve enhancement on MRI, as seen in this patient, may suggest poor prognosis.9,10,11,12 Treatment with corticosteroids has been shown to decrease incomplete recovery by 30-40% and has a Number Needed to Treat of 10.8,13 Though it is presumed that HSV is the underlying cause in the majority of cases, there is controversy regarding the use of antivirals, such as acyclovir. A recent Cochrane review does not support treating Bell's palsy with antivirals alone or in conjunction with corticosteroids.13 Therefore, it is widely accepted that all patients receive 1 week of 60-80 mg prednisone, and only those with severe cases additionally receive 400 mg acyclovir every 6 hours for 5 days.3,8 Additionally, all patients should receive an eye patch and eye lubricant to prevent injury and vision loss, which are the most feared and most common complications of Bell's palsy.3

Conclusion

Bell's palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. It can present with other cranial nerve involvement, which should prompt evaluation with CT and/or MRI to rule out more serious pathology. Most cases resolve spontaneously, but corticosteroids facilitate resolution, and eye care is paramount to prevent injury and vision loss.

Table 1: Cranial nerve functions and examination maneuvers and findings14,15,16

|

Cranial Nerve |

Motor Function |

Sensory Function |

Exam Maneuvers & Findings |

|

I, Olfactory |

- |

Smell |

Occlude 1 nostril and sniff coffee grounds or cinnamon → deficit on affected side |

|

II, Optic |

- |

Vision |

Visual fields, visual acuity → deficit on affected side |

|

III, Oculomotor |

Superior rectus, inferior rectus, medial rectus, inferior oblique, levator palpebrae, pupillary sphincter, ciliary muscles |

- |

H-test of ocular movements → inability to move eye superiorly, superomedially, medially, inferiorly, inferolaterally Light reflex → dilated pupil without constriction. Ptosis on affected side |

|

IV, Trochlear |

Superior oblique muscle |

- |

H-test of ocular movements → inability to move eye inferomedially |

|

V, Trigeminal |

Muscles of mastication |

Sensation of face, mouth, cornea |

Pinprick test, corneal reflex → deficit on affected side Palpate clenched jaw and open jaw against resistance → jaw will deviate toward affected side |

|

VI, Abducens |

Lateral rectus muscle |

- |

H-test of ocular movements → inability to move eye laterally |

|

VII, Facial |

Muscles of facial expression |

Taste of anterior ⅔ of tongue |

Eyebrow raise, eyelid squeeze, smile → deficit on affected side; taste deficit on affected side |

|

VIII, Vestibulocochlear |

- |

Hearing, orientation of head in space |

Whisper into ear while occluding the opposite ear → deficit on affected side Assess nystagmus → beats away from affected side or vertigo |

|

IX, Glossopharyngeal |

Stylopharyngeous and pharyngeal constrictor muscles |

Taste of posterior ⅓ of tongue, sensation of tongue, oropharynx, middle ear, and ear canal |

Say "ah" → affected side of oropharynx will not lift; uvula deviates away from affected side |

|

X, Vagus |

Pharyngeal, soft palate, and laryngeal muscles |

Visceral innervation of thoracic and abdominal organs; taste of base of tongue and epiglottis |

Say "ah" → affected side of oropharynx will not lift; uvula deviates away from affected side; hoarseness |

|

XI, Accessory |

Sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles |

- |

Turn head and shrug shoulder against resistance → difficulty on affected side |

|

XII, Hypoglossal |

Genioglossus, geniohyoid, hyoglossus, and styloglossus muscles of the tongue |

- |

Protrude tongue → Deviation toward affected side |

Take-Home Points

- Facial nerve palsy can present with other cranial nerve involvement.

- CVA must be ruled out with MRI when facial paralysis involves other neurological findings.

- Peripheral causes of facial paralysis present with forehead involvement.

- Treatment of Bell's palsy includes corticosteroids, an eye shield, and eye lubricant.

References

- Ronthal M. Bell’s palsy: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis in adults. Uptodate.com. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bells-palsy-pathogenesis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis-in-adults?search=bell%20palsy%20presentation&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated Oct 2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

- Benatar M, Edlow J. The spectrum of cranial neuropathy in patients with Bell’s palsy. Arch Internal Med. 2004;164(21):2383-2385. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.21.2383

- Warner MJ, Hutchison J, Varacallo M. Bell palsy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. [Updated 2019 Jul 30]. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482290/. Accessed May 3, 2020.

- Morris AM, Deeks SL, HILL MD, et al. Annualized incidence and spectrum of illness from an outbreak investigation of Bell’s palsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2002;21(5):255-61. doi:10.1159/000065645

- Adour KK. Cranial polyneuritis and Bell palsy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102(5)262-264. doi:10.1001/archotol.1976.00780100048003

- Pavlidis P, Cámara RJA, Kekes G, et al. Bilateral taste disorders in patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome and Bell palsy. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(4):807-815. doi:10.1002/ana.25210

- Fahimi J, Navi BB, Kamel H. Potential misdiagnoses of Bell’s palsy in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(4):428-34. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.06.022

- Ronthal M. Bell’s palsy: Treatment and prognosis in adults. Uptodate.com. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bells-palsy-treatment-and-prognosis-in-adults?search=bell%20palsy%20presentation&topicRef=5281&source=see_link. Updated Nov 2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

- Kress BP, Griesbeck F, Efinger K, et al. Bell’s palsy: what is the prognostic value of measurements of signal intensity increases with contrast enhancement on MRI? Neuroradiology. 2002;44(5):428-33. doi:10.1007/s00234-001-0738-y

- Girard N, Poncet M, Chays A, et al. MRI exploration of the intrapetrous facial nerve. J Neuroradiol. 1993;20(4):226-38. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.evms.idm.noclc.org/pubmed/8308541. Accessed May 3, 2020.

- Jun BC, Chang KH, Lee SJ, et all. Clinical feasibility of temporal bone magnetic resonance imagin as a prognostic tool in idiopathic acute facial palsy. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(9):893-6. doi:10.1017/S0022215112001417

- Kress B, Griesbeck F, Stippich C, et all. Bell palsy: quantitative analysis of MR imaging data as a method of predicting outcome. Radiology. 2004;230(2):504-9. doi:10.1148/radiol.2302021353

- Madhok VB, Gagyor I, Fergus D, et al. Corticosteroids for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2016;7: CD001942.

- Duke University Medical School. Neurosciences Learning Resources Lab 4 - Cranial Nerve and Neuromodulatory Nuclei of the Brainstem. Duke.edu. https://web.duke.edu/brain/lab04/lab04.html. Updated January 7, 2018. Accessed June 2, 2020.