Hydrocephalus is the excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the ventricular system around the brain.

An increase of volume within this closed system causes an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) that compresses brain tissue and can result in brain injury and death.1 The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) estimates that hydrocephalus occurs in 1-2 out of every 1000 children born in the U.S.2

The process is either congenital (spina bifida, neural tube defects, myelomeningocele, Dandy-Walker malformation, etc.) or acquired (tumors, malignancy, infection, hemorrhage).1 It is diagnosed by brain imaging, and managed by placement of a shunt to drain the excess CSF and reduce the elevated ICP.

Emergency physicians should be familiar with the shunt concept and aware of potential complications that can arise in this population.

Anatomy

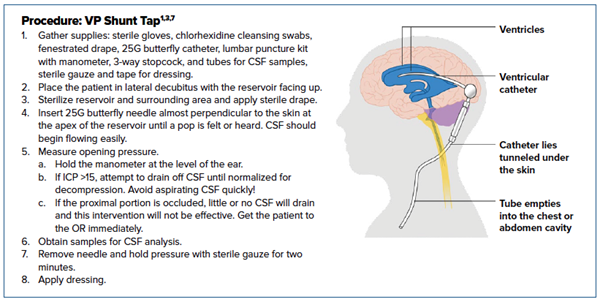

Although there are several different types of shunts, the most common is the ventriculoperitoneal. It consists of 4 main components: a proximal catheter that inserts directly into the lateral ventricle in the posterior-occipital region, a one-way valve, a reservoir, and a distal catheter that runs down the neck and chest wall and terminates in the peritoneal cavity.

The valve is programmed by a neurosurgeon and works by draining CSF when ventricular pressure exceeds a set value (normal 8-12 mmHG). The reservoir is a small, localized collection of CSF that is available for removal if indicated. Both the valve and reservoir are palpable beneath the posterior scalp.1

Potential Issues

Complications with VP shunts are common, in particular shunt malfunction and infection. Malfunction can be further categorized into proximal shunt obstruction, overshunting, slit ventricles, and distal shunt obstruction. On average, VP shunts have a 98% failure rate over 10 years, and mortality from malfunction is estimated to be between 1-2.7%.1

When the proximal portion of the catheter becomes obstructed, excess CSF is unable to drain out of the ventricle. This is a neurosurgical emergency. Obstruction can be caused by migration of intraventricular catheter, intracranial hemorrhage, tumor, fibrosis, or debris. The distal portion of the shunt can also become obstructed by thrombosis, clogging, kinking, fracture or migration of distal catheter portion. Surrounding intra-abdominal organs, omentum, and pseudocysts can also compress the distal portion.

Another well-known shunt complication is overshunting, also known as over-drainage. If minor, this can result in postural headaches; however, if sudden, can precipitate herniation. There is an accompanying risk of subdural hematoma if the bridging veins get torn in the process. Management of overshunting in the immediate period includes lying the patient down, and eventually, reprogramming of the system by the neurosurgeon. If the overshunting is chronic, slit ventricle syndrome can result. This manifests as minor episodic headaches, nausea and vomiting, and ataxia.1, 3

Infection of the shunt is another common complication that occurs most frequently in the first six months after placement and in infants under 3 months of age.3 Mortality is as high as 60%. The typical pathogens are Gram positive organisms within the Staphylococcal species.1 Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria are also implicated and precipitate more lethal infections. In general, a high index of suspicion should be maintained when evaluating a patient with a shunt to avoid missing potentially devastating pathology.3,4

Presentation

A patient with a shunt complication can present with any spectrum of symptoms ranging from lethargy or slight change in behavior to full-blown, life-threatening hydrocephalus. The most common presenting symptoms suggestive of shunt complication are vomiting and lethargy.5 Other presenting symptoms include severe headache, photophobia, meningismus, and altered level of consciousness.

Concerning findings on examination of the pediatric cranium include bulging fontanelles, increasing cranial size, thin or shiny scalp, palpable splitting of the cranial sutures, or changes in percussion of the cranium (Macewen sign).1

On neurologic assessment, you may identify a new deficit, papilledema, or limited upward gaze.

If the patient has severely increased ICP with impending herniation, you may see autonomic instability, coma, or respiratory compromise.

If the shunt or CSF is infected, the patient may present with signs of cellulitic changes overlying the shunt.3

Patients may or may not present with a fever, so lack of fever does not rule out infection in this population.5

Evaluation and Management

A systematic approach should be employed when evaluating a patient with a possible VP shunt complication.

First, perform a thorough neurological exam. Compare this to the patient’s documented baseline in the EMR and by consulting with the patient’s guardian or caregiver.

Next, palpate the shunt. If the shunt is flat or slow to refill (more than 3-5 seconds), it is possible that the excess CSF is not being drained from the ventricles and a proximal malfunction should be considered. If the shunt is firm or difficult to compress, it can indicate that CSF is not draining into the peritoneum and is suggestive of distal malfunction. Any overlying redness, swelling, or tenderness can indicate shunt infection.1, 3

If the patient is stable, your workup will include laboratory studies and imaging. Several imaging modalities are used to evaluate a VP shunt. The shunt series, which is a set of AP and lateral radiographs of the skull, chest, and abdomen, will reveal if any portion of the shunt has migrated or kinked, and is extremely specific for malfunction although not sensitive. Sensitivity improves when the shunt series is combined with a head CT that can reveal any acute intracranial pathology and reveal the size of the ventricles.1 MRI or ultrasound of the optic nerve sheath diameter can also be utilized.6

If infection is suspected, the typical workup with CBC, blood cultures and inflammatory markers is appropriate.

If the patient is hemodynamically unstable and presenting with signs and symptoms of hydrocephalus (seizing, unresponsive, significantly altered, not protecting airway, etc.), consult Neurosurgery immediately and consider emergent intubation and VP shunt tap. Elevate the head of bed, hyperventilate with BVM, and initiate hyperosmolar pharmacotherapy.

When intubating, take caution to avoid further increases in ICP. Do not use ketamine or a depolarizing paralytic, pretreat pain with fentanyl (1 mg/kg), sedate with propofol, and consider lidocaine (1mg/kg) for cough suppression.3

If an emergent shunt tap is indicated, speak with a neurosurgeon. A shunt tap is best done by a specialist, but is within the ED scope of practice when a patient is critically ill and a neurosurgeon is not immediately available. Be aware of complications, which include precipitating an intraventricular hemorrhage, but know that infection caused by shunt tap is rare (<1%).1 Remember to send CSF samples for typical meningitis/encephalitis workup.

Procedure: VP Shunt Tap1, 3,7

- Gather supplies: sterile gloves, chlorhexidine cleansing swabs, fenestrated drape, 25G butterfly catheter, lumbar puncture kit with manometer, 3-way stopcock, and tubes for CSF samples, sterile gauze, and tape for dressing.

- Place the patient in lateral decubitus with the reservoir facing up.

- Sterilize reservoir and surrounding area and apply sterile drape.

- Insert 25G butterfly needle almost perpendicular to the skin at the apex of the reservoir until a pop is felt or heard. CSF should begin flowing easily.

- Measure opening pressure.

- Hold the manometer at the level of the ear.

- If ICP >15, attempt to drain off CSF until normalized for decompression. Avoid aspirating CSF quickly!

- If the proximal portion is occluded, little or no CSF will drain and this intervention will not be effective. Get the patient to the OR immediately.

- Obtain samples for CSF analysis.

- Remove needle and hold pressure with sterile gauze for two minutes.

- Apply dressing.

Disposition

Prompt neurosurgical consultation should be sought whenever a shunt complication is suspected, as shunt revision or replacement may be necessary for definitive treatment. The patient should be admitted for close monitoring and intervention if indicated.

In patients in whom infection is suspected, treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated and CSF samples sent for analysis.

In the rare event that a complete workup of the shunt is negative, and the patient looks and feels well, the neurosurgeon may determine that the patient can follow up in an outpatient setting.

References

- Ferras M, Mccauley N, Stead T, Ganti L, Desai B. Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts in the Emergency Department: A Review. Cureus. 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6857

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. April 2020. Hydrocephalus Fact Sheet (NIH Publication No. 20-NS-385).

- Key CB, Rothrock SG, Falk JL. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt complications: an emergency medicine perspective. Pediatric Emergency Care. 1995;11(5):265-273. doi:10.1097/00006565-199510000-00001

- Garton HJ, Piatt JH. Hydrocephalus. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2004;51(2):305-325. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2003.12.002

- Marmor I, Carbell G, Koplowitz J, et al. Bradycardia Without Hypertension. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. doi:10.1097/pec.0000000000002049

- Jayanth A, Benabbas R, Chao J, Sinert R. Diagnostic modalities to determine ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021;39:180-189. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.024

- Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW. Roberts and Hedges Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.