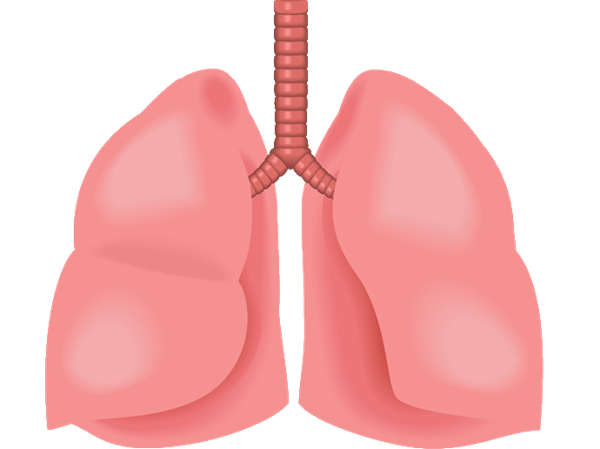

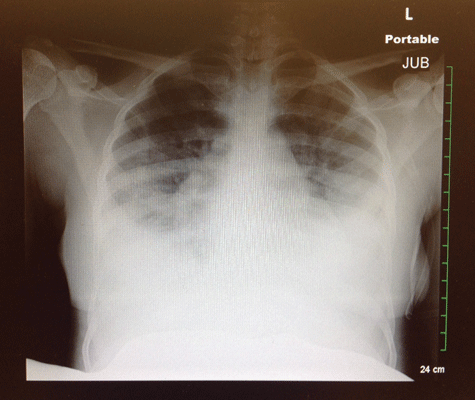

Case. A 26-year-old female presents to your ED with four days of fever, shortness of breath (SOB), cough, and substernal chest pain. In two previous visits over the same time, she was diagnosed with a URI and discharged. Her vitals on presentation are: BP 136/80, P 90, R 19, T 98.3, O2 Sat 88% on RA, but improving to 96% on 3LNC. A chest X-ray shows diffuse bilateral pleural effusions (Image 1), acutely changed from the X-ray she'd received at her visit two days earlier (Image 2). On reassessment, she is noted to be tachypnic with a respiratory rate of 34 breaths per minute and desating to 83% when taken off O2. Further history reveals that, just prior to the onset of her symptoms, she'd had “her hips done,” referring to gluteal injections received at an unlicensed beauty shop five days earlier.

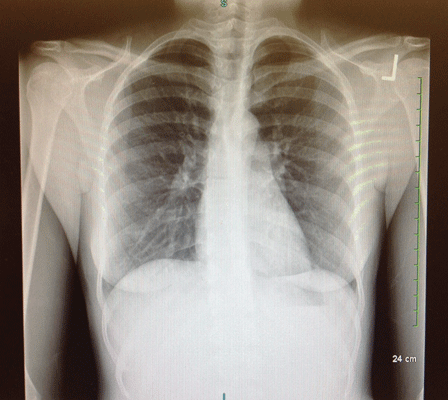

Her symptoms began with a dry cough and SOB within hours of the procedure. A CT scan of the chest (Image 3) shows findings concerning for an embolism. She is admitted to the ICU and later intubated for worsening respiratory distress. Bronchoscopy the next day demonstrates frank alveolar hemorrhage, consistent with the diagnosis of silicone embolism. After a four-day ICU stay, she is successfully extubated and discharged home on a steroid taper.

Most residents are very familiar with pulmonary embolisms (PEs), as they are a commonly seen condition in the emergency department. The presentation can vary on a wide spectrum of severity ranging from relatively mild symptoms to cardiovascular compromise, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest. While the most common type of embolisms seen in emergency departments are due to inappropriate activation of the clotting cascade leading to a deep vein thrombosis with subsequent embolization to the pulmonary vessels, there are other types of emboli that can also occur. What makes treating this other type of emboli so tricky is that unlike traditional PEs, they are not the result of coagulopathy and cannot be treated with blood thinners like lovenox or heparin. Taking a thorough history is crucial to making the right diagnosis and starting the appropriate treatment.

Anticoagulating these patients carries the potential for disaster.

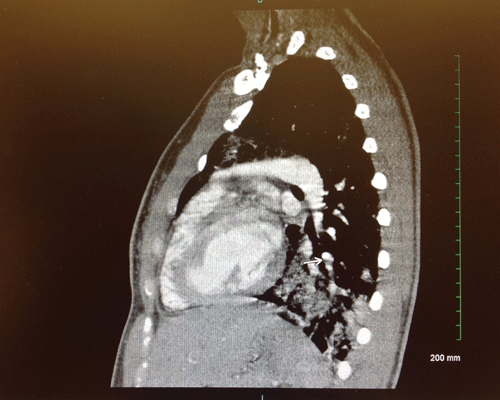

Silicone Embolism

As the incidence of cosmetic procedures has increased, so has the incidence of silicone emboli. Silicone is touted as ideal for cosmetic surgery because it is chemically inert, thermally stable, and causes minimal tissue reactivity. However, complications can arise, particularly when procedures are performed by those unfamiliar with the potential risks.1 As early as the 1980s, clinicians began documenting cases of patients developing respiratory compromise after cosmetic procedures involving silicone injection.2 Silicone emboli usually occur in the setting of such procedures, although more commonly in procedures where silicone is injected directly into the subcutaneous tissue, rather than as part of a prosthesis or implant.3 Like most PEs, silicone embolisms can present with a range of severity, from mild chest pain to hypoxia. The typical presenting symptoms include hypoxemia, fever, and a petichial rash.4 Alveolar hemorrhage is commonly reported in more severe cases, and neurologic dysfunction can be present in as many as one-third of all patients. The presence of neurologic symptoms — such as confusion, altered mental status, or seizure — is a poor prognostic indicator and is associated with rapid decline and up to 100% mortality.5

Diagnosis. The diagnosis of a silicone embolism must be made within historical context (typically a recent cosmetic procedure) and requires CT imaging.4 It is important to note that bronchoscopy almost never demonstrates the presence of silicone particles in the lungs and is usually only significant for frank hemorrhage. The absence of foreign matter in the bronchiolar aspirate does not exclude the diagnosis of silicone embolism.1

Treatment. Treatment for silicone embolism syndrome is largely supportive.4 Steroids are frequently given to decrease airway inflammation, although evidence to support this practice is largely anecdotal. Patients may need intubation and ventilator support if symptoms are severe. Patients with silicone emboli should not receive anticoagulation. Inappropriately anticoagulating these patients carries the potential for disaster as it may worsen alveolar hemorrhage and cause an acute decline in respiratory function.

Fat Embolism

A fat embolism typically presents with the triad of hypoxemia, petichial rash, and neurologic abnormalities.6 Fat emboli are associated with fractures of the pelvis and long bones, occurring more frequently in closed fractures than in open ones.4 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but the two prevailing theories are that they are either the result of traumatic disruption of fat globules from the bone marrow into the blood stream or from the formation of toxic intermediates during degradation of intravascular lipids.6 Whatever the cause, symptoms usually begin 24 to 72 hours after the inciting event.7 Neurologic symptoms may range from confusion and altered mental status to seizures. However, unlike patients with a silicone embolism, neurologic symptoms in patients with fat embolisms carry no increased mortality and are usually fully reversible.8

Diagnosis. Like silicone embolism, the diagnosis of fat embolism is made by the presentation of hypoxia with CT findings suggestive of PE in the appropriate clinical setting. A peticheal rash is said to be pathoneumonic of fat embolism, but because the rash occurs in less than 50% of patients, most patients will just present with hypoxia or respiratory distress. Bronchoscopy may or may not show fat particles in the lungs, but it is not considered necessary for the diagnosis.4

Treatment. The treatment for fat embolism syndrome is supportive. Again, steroids may be considered for airway inflammation, but there is limited data to support this practice.4 Most patients with fat embolisms will recover fully. Just as in the patients with silicone embolism syndrome, there is no role for anticoagulation in these patients.

Conclusion

When evaluating a patient for a potential pulmonary embolism, it is crucial to consider the circumstances under which they present. Always be sure to take a thorough history of the events leading up to the onset of their symptoms, ask about recent cosmetic procedures, and be mindful of any patient with a recent fracture who complains of shortness of breath. Making the correct diagnosis is vital in these patients, as inappropriate anticoagulation may have disastrous consequences.

REFERENCES

- Chung KY, Kim SH, Kwon IH, Choi YS, Noh TW, Kwon TJ, Shin DH. “Clinicopathologic review of pulmonary silicone embolism with special emphasis on the resultant histologic diversity in the lung--a review of five cases.” Yonsei Med J. 2002;43(2):152.

- Chastre J, Brun P, Soler P, Basset F, Trouillet JL, Fagon JY, Gibert C, Hance AJ. “Acute and latent pneumonitis after subcutaneous injections of silicone in transsexual men.” American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1987;135(1):236.

- Kim CH, Chung DH, Yoo CG, Lee CT, Han SK, Shim YS, Kim YW. “A case of acute pneumonitis induced by injection of silicone for colpoplasty.” Respiration. 2003;70(1):104.

- Weinhouse, Gerald L. “Fat Emoblism.” UpToDate, June-July 2013. Web. 14 Dec. 2014.

- Schmid A, Tzur A, Leshko L, Krieger BP. “Silicone embolism syndrome: a case report, review of the literature, and comparison with fat embolism syndrome.” Chest. 2005;127(6):2276.

- Pell AC, Hughes D, Keating J, Christie J, Busuttil A, Sutherland GR. “Brief report: fulminating fat embolism syndrome caused by paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale.” N Engl J Med. 1993;329(13):926.

- Carr JB, Hansen ST. “Fulminant fat embolism.” Orthopedics 1990; 13:258

- Jacobson DM, Terrence CF, Reinmuth O. “The neurologic manifestations of fat embolism.” Neurology. 1986;36(6):847.