The AAMC launched the Standardized Video Interview (SVI) pilot project for medical students applying to emergency medicine residency programs in summer 2017. The SVI is an online, asynchronous interview designed to assess applicants’ proficiency in two Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies: Interpersonal and Communication Skills and Knowledge of Professional Behavior.1

Questions are presented in text and applicants provide an audio/video response. The purpose of the SVI is to provide easy-to-use and reliable information about applicants’ proficiency on the target competencies, balance emphasis on Step scores, and provide a new set of standardized evaluation criteria that may affect the student population invited to in-person interviews.2

The addition of the SVI to the residency selection process has generated questions about added value to the selection process, how applicants should prepare, and whether the setting in which they complete the SVI influences their score. Answers to these questions are particularly important because they could be used to better inform all students about how to prepare, and address their concerns about the amount of time needed to prepare for the SVI.

Methods

All EM applicants who submitted a completed SVI were invited to participate in 2 online surveys about their experience preparing for and taking the SVI. The first survey contained 11 questions and was administered immediately following the SVI. The response rate was 83% (n = 2,906). The second survey contained 29 questions and was administered between October and November 2017. The response rate was 58% (n = 2,074).

Applicants’ responses were linked to SVI scores for applicants who provided email addresses as part of the survey; only responses that could be linked to SVI scores were retained for analyses.3

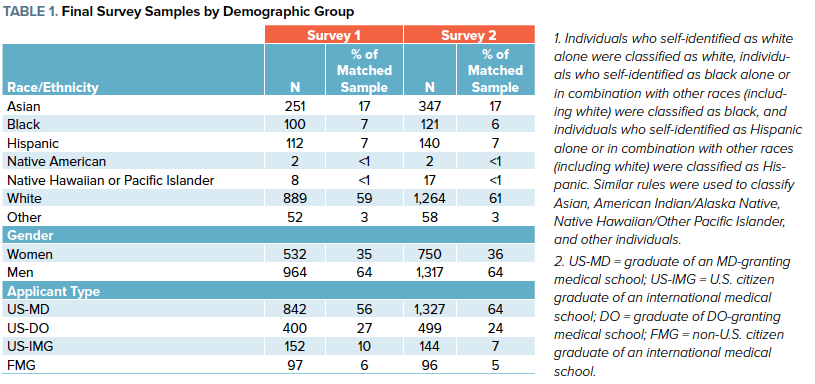

Descriptive statistics, including counts, mean, and standard deviations were computed. Table 1 summarizes the sample by demographic group.

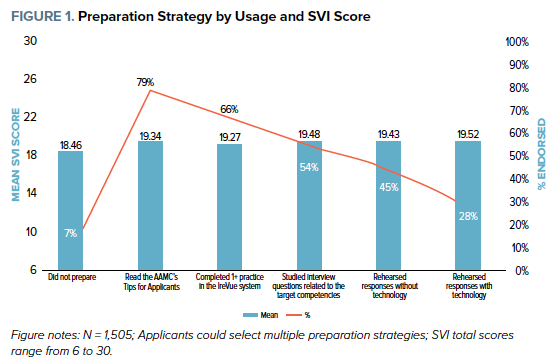

Preparation Strategy

Applicants used a variety of strategies to prepare for the SVI. As shown in Figure 1, most participants reported reading AAMC’s Tips for Applicants (79%), completing at least one practice question in advance (66%), and/or studying interview questions related to the target competencies (54%). Only 7% did not prepare in advance and their scores were significantly lower than applicants using any preparation strategy (t (1503) = -3.405, p = .001). There were no practical differences in SVI scores by preparation strategy.

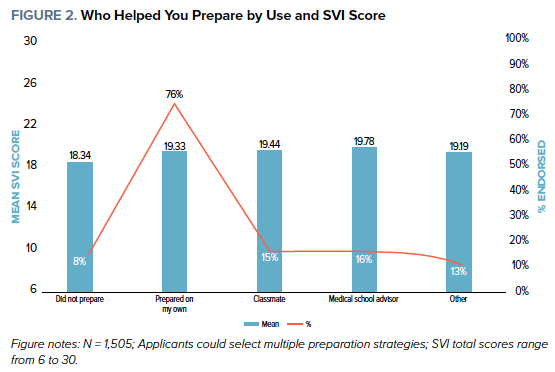

Who Helped You Prepare

As shown in Figure 2, 76% of applicants prepared for the SVI on their own, 16% prepared with a medical school advisor, 15% prepared with classmates, and 8% did not prepare in advance. SVI scores did not differ based on who helped the applicant prepare for the SVI, but applicants who did not prepare for the SVI had significantly lower SVI scores (t (1503) = -3.582, p < .001).

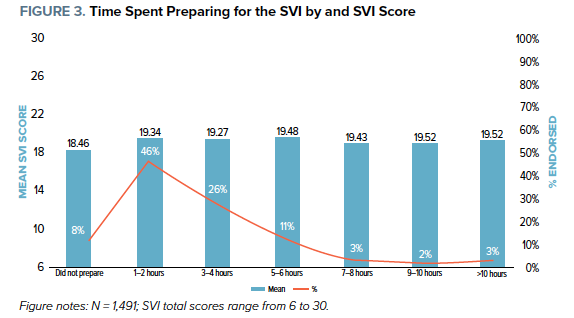

Hours Spent Preparing for the SVI

As shown in Figure 3, most applicants spent some time preparing for the SVI. Forty-six percent of applicants spent 1-2 hours and 26% spent 3-4 hours preparing for the SVI. About eight percent did not prepare for the SVI. Applicants who did not prepare at all for the SVI had slightly lower scores than applicants who spent between 1-6 hours preparing (t (1419) = -4.138, p <.001). Among those who prepared for the SVI, the amount of time spent preparing did not affect SVI scores.

Taking the Interview

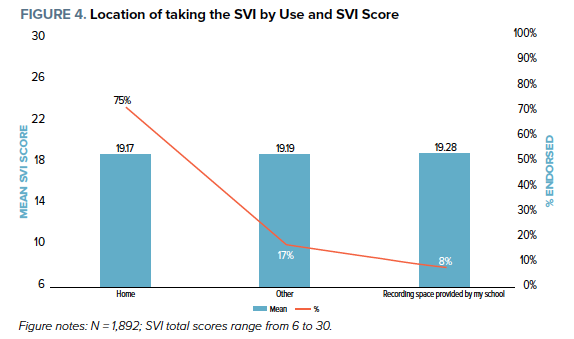

Because of the flexible nature of the SVI, applicants could record the interview at various locations. As shown in Figure 4, the majority of applicants completed the SVI at home (75%), whereas others completed it at a recording space arranged by their school (8%) or other locations like hotels or offices (17%). Location did not influence final SVI score, suggesting that applicants should complete the SVI in the location that is most convenient for them (and has a good internet connection).

Key Take-Aways for Those Taking the SVI in 2018

- Use the preparation methods you need to feel comfortable before taking the SVI, but more than a couple of hours of practicing does not seem to be necessary. SVI scores did not differ based on number of hours spent preparing for the SVI, nor did they differ by preparation strategy. However, students are still advised to 10% read the AAMC’s Tips for Applicants as a way to prepare for and familiarize themselves with the SVI.

- Take the SVI at whatever location is convenient for you, as long as there is a good internet connection. Differences in mean SVI scores across recording locations were also insignificant, suggesting that applicants should complete the SVI in any location that makes the applicant comfortable.

FOOTNOTES

- The ACGME core competency Professionalism was renamed Knowledge of Professional Behavior to acknowledge that the video interview is not a direct observation of behavior but rather an inference of an applicant’s proficiency based on their description of past experiences or what they would do in a hypothetical situation.

- Bird S, Blomkalns A, Deiorio NM, Gallahue FE. Stepping up to the plate: Emergency medicine takes a swing at enhancing the residency selection process. AEM Education and Training. 2018;2(1):61-65.

- AAMC researchers linked survey respondents to SVI scores using email addresses provided during the survey and matching with a student’s email provided in ERAS. Responses from 1,401 applicants were excluded from analyses in survey #1 due to having inconsistent email addresses in the survey and in ERAS. There was negligible difference between the average SVI scores for those retained in survey 1 (M=19.22, SD-2.99), survey 2 (M=19.21, SD=3.06), and overall scores to the SVI (M=19.12, SD =3.08).

This article was submitted by the AAMC Writing Group:

Zach Jarou, MD

Denver Health, Department of Emergency Medicine

Erin Karl

University of Minnesota Medical School

Ashely Alker, MD, MPH

University of California School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine

Steven B. Bird, MD

University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Emergency Medicine

Nicole M. Deiorio, MD

Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Emergency Medicine

Jeffrey Druck, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine

Fiona Gallahue, MD

University of Washington, Division of Emergency Medicine

Katherine M. Hiller, MD, MPH

University of Arizona, Department of Emergency Medicine

Ava Pierce, MD

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine

Laura Fletcher, MA

Association of American Medical Colleges

Thomas Geiger, MA

Association of American Medical Colleges