A 31-year-old multiparous woman who is 7 days postpartum after a c-section presents to the emergency department for the second time complaining of a severe headache. On her initial visit, she was diagnosed with a spinal headache (post epidural anesthesia) and had an epidural blood patch placed. She states the patch helped lower her pain slightly, but that the pain has continued to stay at an 8/10. She otherwise had an uneventful pregnancy and delivered at 39 weeks estimated gestational age. A head CT-scan is performed and reveals a subdural hematoma.

Intracranial Hemorrhage Types

To review, there are 4 different types of intracranial hemorrhages: epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

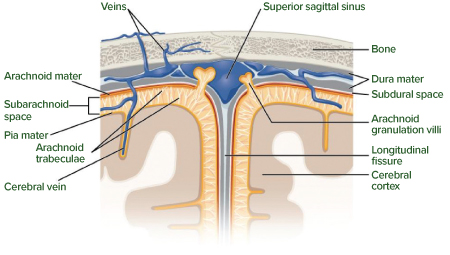

The meninges consist of three very different layers of protective tissues that surround the brain and spinal cord (Figure 1). When damage occurs to the skull or surrounding areas, blood can accumulate in the limited intracranial space and cause compressive damage.

Epidural hematoma occurs between the skull and the dura mater. It is most commonly seen after trauma and fracture to the temporal bone, which results in the rupture of the middle meningeal artery. CT scan of the bleed will demonstrate biconvex, hyperdense, lentiform appearance that does not cross suture lines.

Subdural hematoma occurs in the space between the dura mater and the arachnoid matter called the subdural space. The blood is from the rupture of fragile bridging veins, which can sheer even in relatively low-impact injuries in elderly and alcoholics. CT scan of the blood will demonstrate crescent-shaped hemorrhage that crosses suture lines.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is usually seen in patients with congenital risk factors for intracranial bleeds but can also be idiopathic or secondary to trauma. Risk factors include berry aneurysms secondary to multiple genetic diseases and arteriovenous malformations. The patients tend to bleed into the brain such as the regions of the sulci and ventricles.

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage occurs in patients with amyloid angiopathy, neoplasms, vasculitis, and uncontrolled systemic hypertension, among other etiologies. The blood is traditionally found in the internal capsule and basal ganglia region.

Pathophysiology of PDPH vs. CSH

A pregnant patient with a headache has a broad differential, which includes the following: pre-eclampsia, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), hypertensive emergency, drug-induced headaches, migraines, postdural puncture headache, and intracranial hemorrhage. Complications from spinal anesthesia are very rare, however, if not diagnosed in a timely fashion, can become life-threatening.

Post epidural puncture

headache (PDPH) is a relatively common complication, occurring in around 40% of the cases. The pathophysiology is as follows:

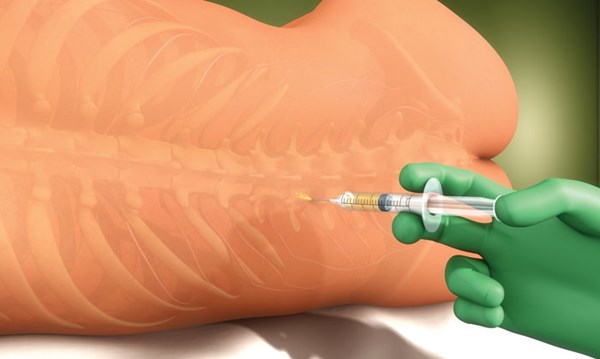

Epidural needle inserted for spinal anesthesia †’ leakage of CSF fluid †’ caudal displacement of intracranial structures †’ stretching of pain sensitive sinuses, blood vessels, and the dura †’ spinal headache (spinal headache does not progress if the CSF leakage stops spontaneous or epidural blood patch is placed correctly).

Cerebral Subdural Hematoma (CSH) is a very rare post-epidural/post-lumbar puncture complication, occurring in less than 0.05% of patients. Pathophysiology commonly theorized for CSH secondary to epidural puncture is as follows:

Epidural needle inserted for spinal anesthesia †’ leakage of CSF fluid †’ caudal displacement of intracranial structures †’ stretching of pain sensitive sinuses, blood vessels, and the dura †’ spinal headache †’ incorrectly placed epidural blood patch/no spontaneous closure of CSF leakage †’ continual loss of CSF †’ low CSF pressure †’ sheering forces on fragile bridging veins †’ subdural hematoma

Prevention and Treatment

The most important intervention for prevention of a cerebral subdural hematoma secondary to epidural anesthesia is a correctly placed epidural blood patch. This should immediately alleviate a patient's headache, while more importantly preventing the progression from PDPH to CSH.

If a subdural hematoma does occur, however, most will improve on their own via reabsorption and require inpatient monitoring only. Patients are recommended to be monitored using the Markwalder Grading System as a prognostic score for chronic subdural:

- 0 MGS Score 0: Neurologically intact

- 1 MGS Score 1: Alert and oriented; mild symptoms such as headache; absent or mild neurological deficit, such as reflex asymmetry

- 2 MGS Score 2: Drowsy or disoriented with variable neurological deficit, such as hemiparesis

- 3 MGS Score 3: Stuporous but responding appropriately to noxious stimuli; severe focal signs such as hemiplegia

- 4 MGS Score 4: Comatose with absent motor responses to painful stimuli; decerebrate or decorticate posturing

Large subdural hematomas can progress rapidly and result in acute neurological changes. While awaiting neurosurgical evaluation for possible craniotomy and evacuation of hematoma, it becomes very important to monitor the following:

- Blood pressure: Blood pressure changes are an indicator of increased intracranial pressure (Cushing's Triad: bradycardia, irregular respirations, and systolic hypertension with widening pulse pressures). Blood pressure control is important in these patients to prevent further extension of the bleeding, with a goal recommended systolic blood pressure of <140 mmHg.

- Seizures: Although there is no indication to start patients on seizure prophylaxis, it is important to monitor the patient for development of seizures. Levetiracetam and phenytoin would be the traditional treatment options. It is important to note that some recommend starting seizure prophylaxis in patients who require evacuation of their hematomas.

- Herniation: In addition to neurosurgical interventions, if there is a concern for acute herniation, emergent maneuvers include mannitol or hypertonic saline, along with brief respiratory hyperventilation maneuvers.

Conclusion

As emergency medicine physicians, it is important to understand that an unrelenting headache in the setting of post-epidural or post-lumbar puncture procedure can be a sign of a serious complication. This patient also serves as an example of the importance of a thorough evaluation on any bounceback visit to the emergency department.