The use of exogenous steroids in septic shock is a controversial issue with inconsistent data on mortality to date. Several studies examine sepsis treatment. What does the evidence show?

Sepsis is a major global health issue with a high mortality rate ranging from 30-45%. Septic shock is a state of dysregulated immune response to an infection which results in metabolic and cellular abnormalities, organ dysfunction, and cardiovascular instability.1 The use of exogenous steroids in septic shock is a controversial issue with inconsistent data on mortality to date. Steroids are thought to modulate the immune response in septic shock patients. The body relies on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the autonomic nervous system and the immune system to respond to stress and infection. There is evidence that the HPA axis becomes dysregulated during sepsis. Exogenous steroids have been shown to improve cardiovascular performance and reduce organ failure.2 However, it remains unclear whether exogenous steroids improve patient-centered outcomes such as hospital length of stay and mortality.

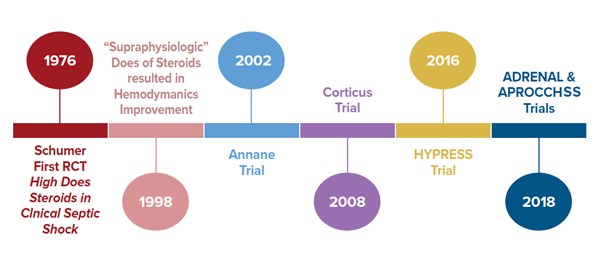

The first reported prospective, randomized trial of steroids in septic shock was in 1976. In this trial, septic shock patients were randomized to receive 3 mg/kg dexamethasone, or 30 mg/kg methylprednisolone, or placebo.3 Their outcome was favorable towards improved mortality. However, the subsequent trials using high dose steroids failed to show improvement in mortality and suggested increase in adverse outcomes.

In 1998, Bollaert et al. reported that “supraphysiologic” dose of methylprednisolone (100 mg IV three times daily for 5 days) resulted in significant improvement in hemodynamics of septic shock patients and beneficial effect on survival.4 The concept of using supraphysiologic low dose steroid re-ignited the interest in investigation of the use of steroids in septic shock.

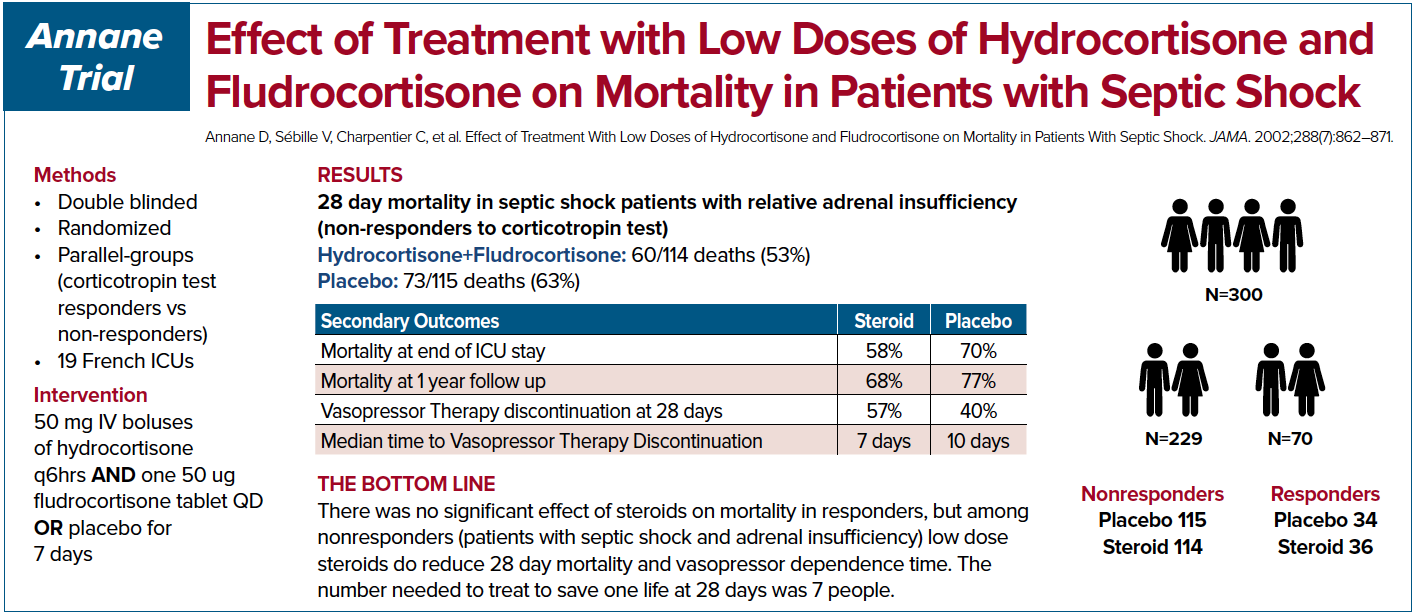

Annane et al. in 2002 conducted a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in France.5 The patients were subdivided into ACTH stimulation responders and non-responders. The authors showed a 28 day mortality and shock resolution benefit.

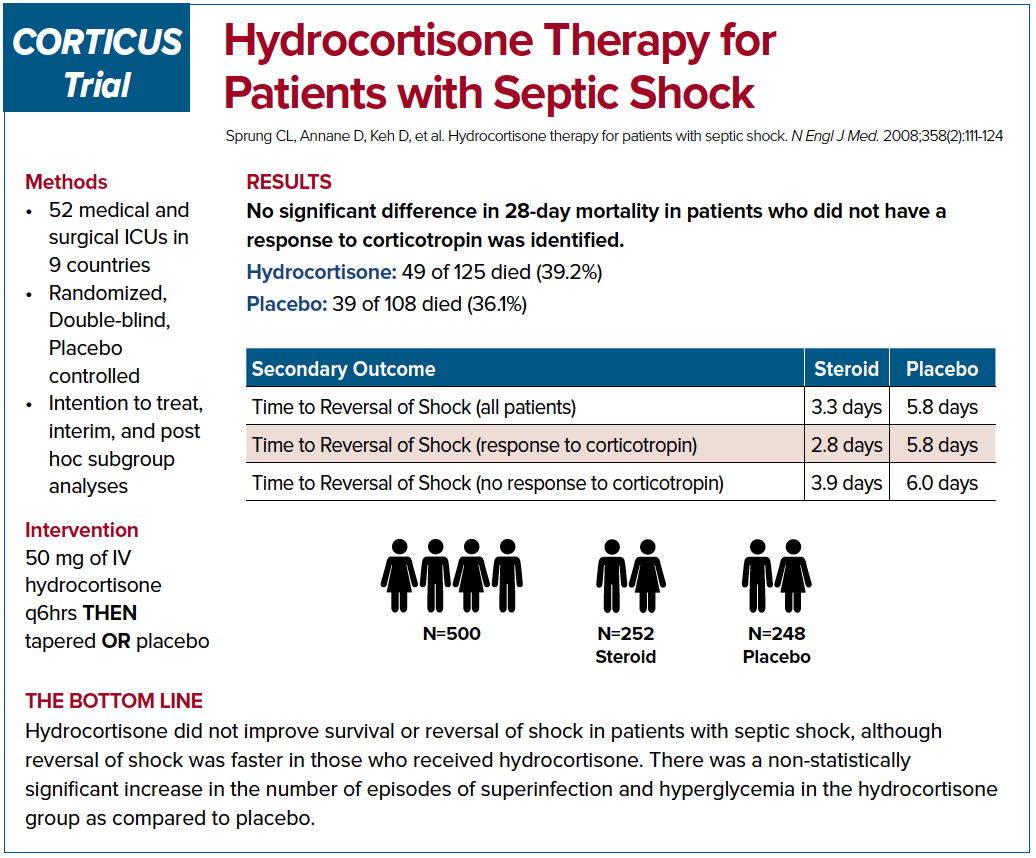

The Corticus trial in 2008 was a multi-centered, randomized study that also looked into 28 day mortality. This study showed that there was no mortality benefit but there was a faster resolution of shock.6 The authors also concluded there was an increased risk of superinfection; however, it wasn’t statistically significant.

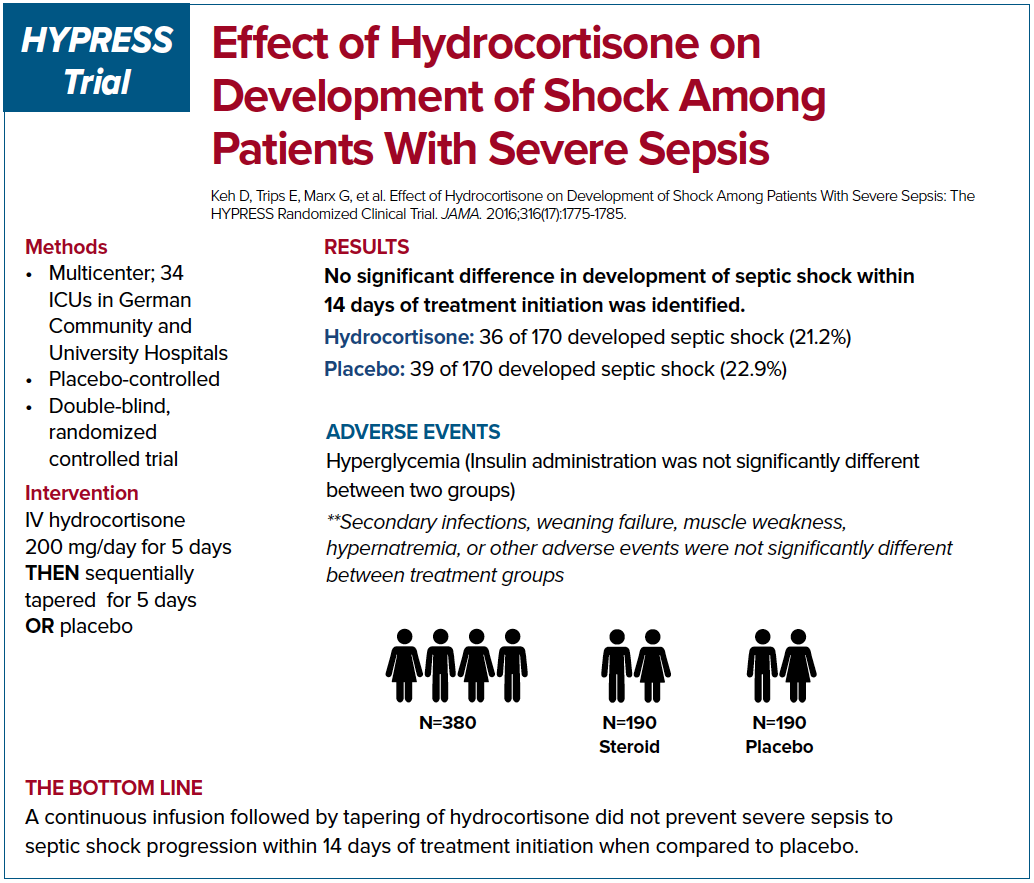

Given the seemingly contradictory findings of the Annane trial compared to the Corticus trial, the practice of using steroid in treating septic shock patients remains controversial. The HYPRESS trial was a multi-centered randomized study in Germany that was designed to examine if steroids would help prevent progression of sepsis into septic shock.7 The primary endpoint was the occurrence of septic shock within 14 days or discharge from the ICU. The authors concluded that the steroids did not prevent the deterioration of sepsis into septic shock. However, the study was underpowered to reach this conclusion.

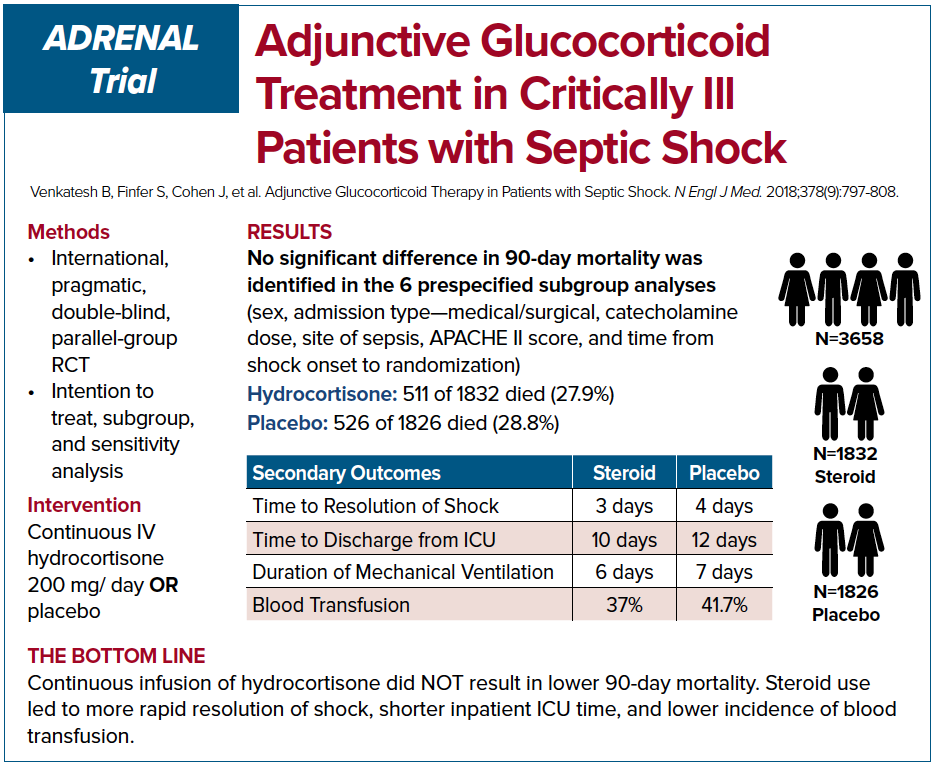

The two most recent trials on this topic, ADRENAL and APROCCHSS, came to seemingly conflicting conclusions as well. ADRENAL trial was an international, double-blinded RCT which enrolled 3,800 patients.8 The authors investigated whether continuous IV infusion of hydrocortisone for 7 days versus placebo would reduce mortality in septic shock. The primary outcome was 90 day mortality. Despite no difference in mortality among the two groups, the authors found important differences in secondary outcomes. The hydrocortisone group had significant benefits in shock reversal, increased ventilator free days, decreased length of stay in the ICU, and fewer blood transfusions. While the hydrocortisone group had increased adverse events compared to placebo most were clinically insignificant and overall hydrocortisone appears fairly safe.

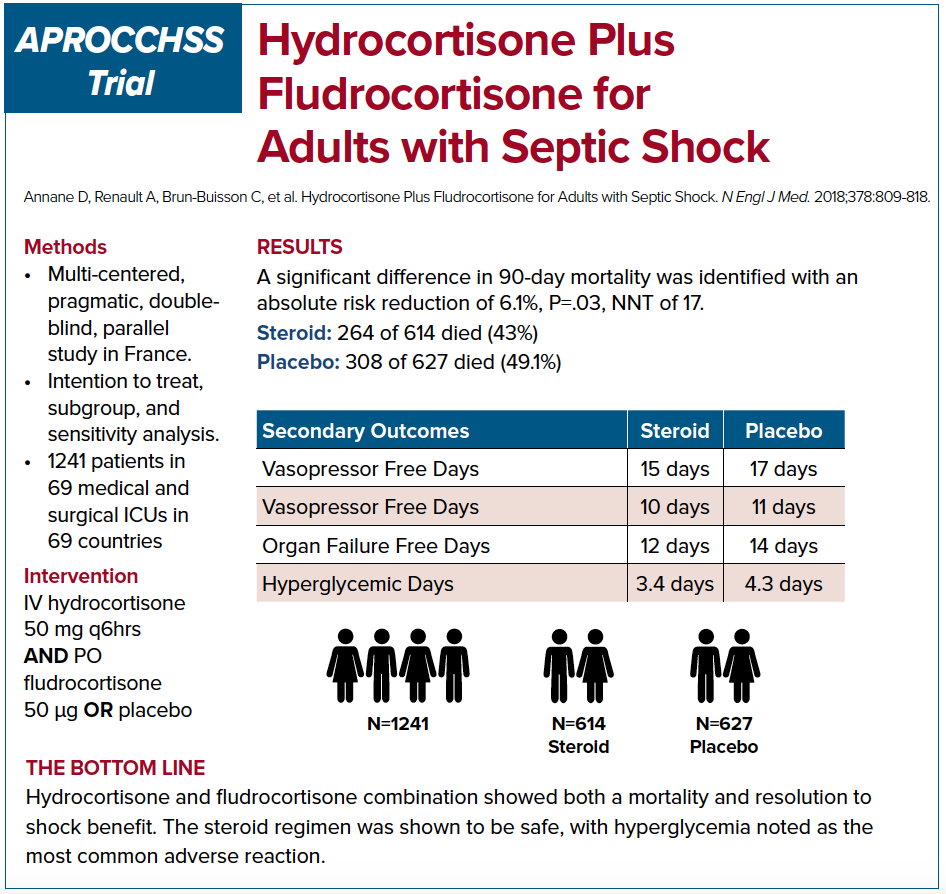

APROCCHSS trial, on the other hand, was a multi-centered, double blinded French RCT that enrolled 1,241 patients in septic shock.9 The study looked into 90 day mortality benefit in patients who were given hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone versus placebo. The study showed a benefit in 90 day mortality along with benefits in secondary outcomes such as vasopressor and ventilator free days, and faster time to shock resolution. It is important to note that at an interim analysis of the ADRENAL study at roughly similar number of enrolled patients as APROCCHSS trial, there was evidence of mortality benefit. Perhaps if the APROCCHSS trial has been expanded further we would no longer see the mortality benefit.

Steroid or No Steroid?

Should we give steroids for septic shock patients as emergency physicians? Is it a reasonable therapy? If so, when should we give it? There is no universal consensus when it comes to the role of steroids in septic shock patients.

Despite seemingly contradictory outcomes of these studies, there is a consistent trend among the secondary outcomes. Steroids appear to lead to shock reversal, decreased vasopressors need, increased ventilator free days, and less time in the ICU. These outcomes are patient-centered and important in reducing critical care burden within the hospital. According to the data that is available so far, it appears that steroids administration would hasten resolution of septic shock. It remains unclear whether steroids improve mortality in septic shock patients. There is also a consistent trend throughout the data available that steroids are fairly safe with most of the adverse outcomes being non-patient centered. Given the safety profile of steroid administration to septic shock patients and its potential benefit in hastening shock resolution, perhaps it is reasonable to consider steroids in management of septic shock patients.

References

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810.

2. Annane D. The role of ACTH and corticosteroids for sepsis and septic shock: an update. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:70.

3. Schumer W. Steroids in the treatment of clinical septic shock. Ann Surg. 1976;184(3):333-341.

4. Bollaert P, Charpentier C, Levy B, Debouverie M, Audibert G, Larcan A. Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic doses of hydrocortisone. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(4):645-650.

5. Annane D, Sébille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of Treatment With Low Doses of Hydrocortisone and Fludrocortisone on Mortality in Patients With Septic Shock. JAMA. 2002;288(7):862–871.

6. Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111-124.

7. Keh D, Trips E, Marx G, et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone on Development of Shock Among Patients With Severe Sepsis: The HYPRESS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1775–1785.

8. Venkatesh B, Finfer S, Cohen J, et al. Adjunctive Glucocorticoid Therapy in Patients with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):797-808.

9. Annane D, Renault A, Brun-Buisson C, et al. Hydrocortisone Plus Fludrocortisone for Adults with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:809-818.