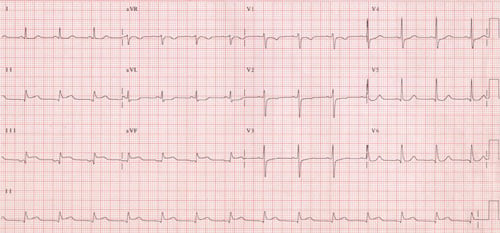

A 32-year-old female presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of severe chest pain. The pain started 3 hours prior in the center of her chest. It is non-radiating, constant, 9/10 on the pain scale, is worse with walking, and has associated dyspnea and vomiting. She denies any past medical history or significant social history and takes no medications. Vital signs are unremarkable. Physical exam reveals a woman who appears uncomfortable, is diaphoretic, and is clutching her left chest in pain. An ECG is immediately performed, which reveals ST-elevation in the inferior leads (Figure 1). Cardiology refuses to take this patient to the cardiac catheterization lab due to her young age. How should you respond?

Figure 1. ECG Reveals ST-elevation in the Inferior Leads

Background

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an uncommon but critically important cause of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Missing this diagnosis has a high risk of fatality if not appropriately treated. SCAD is responsible for 0.1-0.4% of all ACS cases, but has been uniquely associated with females under 50 years old, potentially causing up to 25% of all ACS cases in this patient population.5

Two categories of risk factors are commonly associated with SCAD:

1) Predisposing Arteriopathies

1 or more in 80% of cases.5 Examples include fibromuscular dysplasia

(72% in one study of 168)1, peripartum status, connective tissue disorders, etc.)

2) Precipitating Stressor

Occurred in 56% of cases.1

Examples include recreational drug use, iatrogenic causes, etc.

Experts believe SCAD has been historically underdiagnosed because it is difficult to recognize and is associated with sudden cardiac death. SCAD usually affects only a single vessel, most commonly the LAD (40-70%).5 Typically, pressure-driven expansion of the intramural hematoma eventually leads to occlusion of the true lumen and subsequent myocardial ischemia.

Physical Exam and Imaging/Labs

- Physical exam will reveal the textbook heart attack patient: diaphoretic, in significant pain, ill-appearing

- EKG — ST elevation (25-50%), Ventricular arrhythmias (4-14%)5

- Echocardiogram — often reveals abnormal wall hypokinesis

- Elevated cardiac troponin

- Lactic acidosis — may be elevated depending on the amount of ischemia

Diagnosis

These patients require emergent cardiac angiography.

Management

Recent evidence supports conservative treatment for patients without ongoing or recurrent myocardial ischemia. This is because of the high rate of spontaneous healing (100% at >25 days in one study of 168) and the low success rate of percutaneous cardiac intervention with coronary stenting (only 33% had durable long-term results).1 Overall, conservative treatment is associated with 80% positive long-term outcomes.1 Conservative treatment consists of blood pressure control, dual anti-platelet therapy, and beta-blockers.

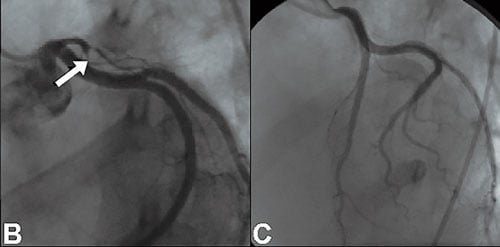

For patients with ongoing or recurrent myocardial ischemia due to SCAD, coronary revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass (CABG) surgery is indicated (Figure 2). Fibrinolysis is not recommended because of risk of increased progression of the intramural hematoma and increased risk of rupture or bleeding.8,10

The recurrence rate for another adverse coronary event is relatively high, estimated at 10-17%.1 This means that close clinical monitoring is necessary with long-term medical treatment with aspirin, beta-blocker, and clopidogrel.5 Close follow-up, particularly with cardiac echo, is important for monitoring long-term cardiac function. Many of these patients can have significantly reduced cardiac ejection fractions and will require aggressive heart failure medical management and cardiac transplant referral.

Overall, however, if the patient makes it through the acute stage of this disease, then there is a good chance of positive long-term outcomes.

Figure 2. Angiography demonstrating LAD occlusion with the tram-track appearance of dissection (left).

Favorable angiographic appearance following stent deployment (right).

Arnold J, West N, van Gaal W, Karamitsos T, Banning A.

Arnold J, West N, van Gaal W, Karamitsos T, Banning A.

The role of intravascular ultrasound in the management of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008;6:24.

Summary

SCAD is a rare phenomenon that typically occurs in patients in their 20-30s, particularly in women, and in patients without any typical ACS risk factors. Making the diagnosis and advocating for a cardiac catheterization in these patients sets them up for positive long-term outcomes. Treatment options include conservative medical therapy unless the patient is experiencing ongoing or recurrent myocardial ischemia, necessitating coronary revascularization by PCI or CABG surgery.

References

- Alfonso F, Bastante T. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Novel Diagnostic Insights From Large Series of Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(5):638-641.

- Alfonso F. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: New Insights From the Tip of the Iceberg? Circulation. 2012;126(6):667-670.

- Alfonso F, Paulo M, Gonzalo N, et al. Diagnosis of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection by Optical Coherence Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(12):1073-1079.

- Biswas M, Sethi A, Voyce S. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Case Report and Review of Literature. Heart Views. 2012;13(4):149-154.

- Douglas PS, Saw J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. UpToDate. Wolters-Kluwer:Waltham, MA.

- Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Association with Predisposing Arteriopathies and Precipitating Stressors and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(5):645-655.

- Saw J, Poulter R, Fung A, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection in Patients With Fibromuscular Dysplasia: A Case Series. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(1):134-37.

- Schmid J, Auer J. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection in a Young Man - Case Report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:22.

- Shafer K, Fields W, Gonzales M. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. EmDocs. N.p., 14 May 2015. Web.

- Tanis W, Stella PR, Kirkels JH, et.al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current Insights And Therapy. Neth Heart J. 2008;16(10):344–349.

- Torres-Ayala Stephanie C. et al. Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep.2015;16:130–135.