Although historically thought to be a rare cause of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) and Myocardial Infarction (MI), recent evidence suggests that Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) might be the culprit in 1-4% of all ACS cases, in 35% of MIs in women under 50 years old, and in 43% of MIs in the peripartum period.1

This case reports a rare case of postpartum cardiac arrest secondary to SCAD in a woman with Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR) Gene Mutation and Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) deficiency.

Case Report

A 37-year-old G5P4A2 female, three days postpartum from spontaneous vaginal delivery of twins at 38 weeks gestation, presented to the ED in cardiac arrest. She was found by her husband with seizure-like activity before becoming pulseless. Her husband started CPR as directed by EMS dispatch and, on arrival, EMS found her pulseless in ventricular fibrillation (VF). Prehospital ACLS interventions included chest compressions, intubation, naloxone, magnesium, multiple rounds of defibrillation, and epinephrine, resulting in brief return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) with re-degeneration to pulseless electric activity on route.

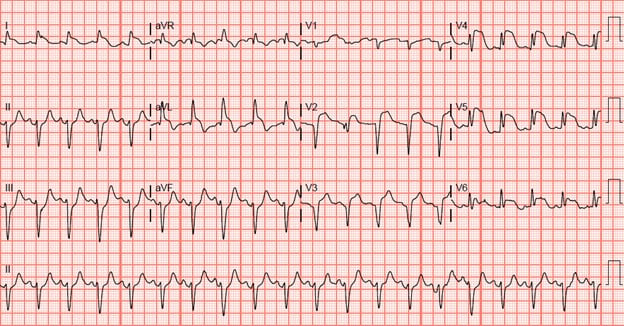

Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was attained during the initial pulse check in the ED, 42 minutes after being found by her husband. Post-ROSC ECG showed anterolateral ST- elevation MI (STEMI) (figure 1), and bedside cardiac echocardiography (ECHO) demonstrated dilated akinetic left ventricular apex, hypokinetic anterior wall, and no signs of right ventricular strain. Arterial blood gas showed pH 6.804, pCO2 58.3, pO283.6, HCO3 8.9, base deficit 25.3.

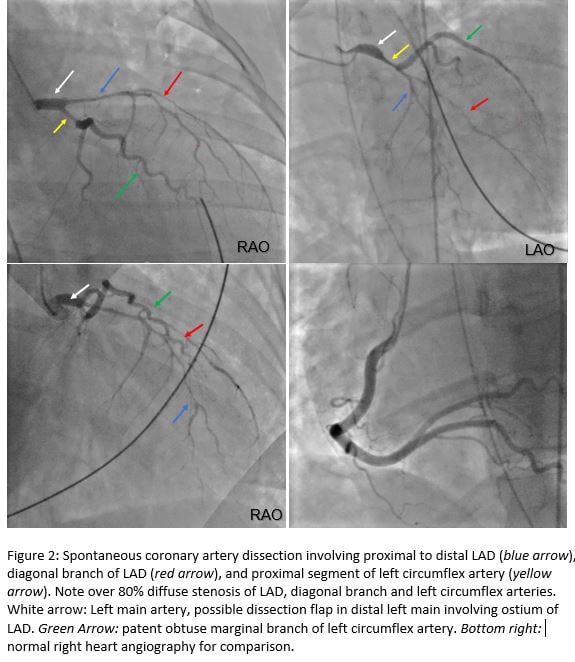

She was given aspirin and heparin while P2Y12 anti-platelet was withheld per interventional cardiology recommendation. Computed tomography angiogram (CTA) did not reveal pulmonary emboli or aortic dissection. Emergent left heart catheterization revealed multi-vessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection involving entire left anterior descending artery (LAD) and its diagonal branch, and the proximal segment of the left circumflex artery (LCX) (figure 2), requiring emergent triple coronary artery bypass grafts (CABG).

Hospital course was complicated by refractory hypoxemia requiring veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, multi-vessel deep vein thrombosis, heart failure with reduced ejection fracture (HFrEF) secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy (left ventricular ejection fracture [LVEF] of 31%), anemia, and consumptive coagulopathy necessitating several blood transfusions. Nonetheless, this patient recovered astonishingly welland was discharged without any neurologic sequelae with a preventative life vest, warfarin, and guideline-directed medical therapy for HFrEF on hospital day 15. Two months later, an echocardiogram demonstrated interval improvement (LVEF 40%), and full-body CTA did not reveal fibromuscular dysplasia. The patient completed cardiac rehab and was happy to be home with her four children.

Discussion

The mechanism of SCAD is thought to be partially related to inflammatory changes and, in peripartum women, a consequence of hemodynamic changes and hormonal effects on weakening the coronary arterial walls. Unlike atherosclerotic arterial dissections in which expansion is limited by vessel scarring and stiffening, SCAD can rapidly expand given vessel fragility. The spontaneous tear on the intimal layer leads to bleeding of the vasa vasorum creating a false lumen. Eventually the blood forms an intramural hematoma leading to vessel occlusion, and subsequently ischemia.1,2,3

Predisposing factors for SCAD include female sex, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), physical or emotional stress, postpartum status, connective tissue disorders, and multiparity.3 While a recent study of 168 patients with SCAD found FMD in 72% of cases,3 most peripartum cases have been observed in women over 33 years old, underlining the likely link with advanced maternal age.1

In addition to her sex, age, multiparity, and postpartum status, our patient had MTHFR gene mutation and PAI-1 deficiency. MTHFR is the rate-limiting enzyme in the methionine metabolism that breaks down homocysteine. Hyperhomocysteinemia is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease through oxidative stress and the stimulation of thrombosis, vascular smooth muscle, and collagen.2 Although there have been a few case reports of SCAD associated with hyperhomocysteinemia in literature,4,5 spontaneous cervical artery dissection and aortic dissection have been linked with this gene mutation.2,4 On the other hand, PAI-1, which is known to be associated with ACS, suppresses fibrinolysis via inhibition of tissue plasminogen activator, leading to decreased plasmin production, and consequently thrombosis, which in theory should have been a protective factor for this patient.6

SCAD patients presenting with an acute MI or hemodynamic instability are often treated with revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention; yet the procedure is exceedingly complex and risky given the instability of the vessel walls. SCADs involving the LAD are often treated with CABG just as in atherosclerotic ischemic MI.

While most patients with SCAD present with non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI), 25-50% present with STEMI, with the LAD being most frequently affected, followed by the left main coronary artery (LM).1,3 While postpartum SCAD is a predictor for recurrence, VT/VF at presentation is associated with worse outcomes, including unplanned revascularization, heart failure, need for implantable defibrillator, and in-hospital death.7

Acid-base status is another important outcome predictor in cardiac arrest. A large study reported mean survivor blood pH of 7.22, mean base deficit 8.8 mmol/l, no survivors with pH < 6.72, base deficit > 25 or HCO3 < 8.6 mmol/l, and only 7.3% of patients with base deficit > 13.2mEq/l surviving without serious neurological deficits,8, 9 making our patient an extreme outlier.

Take-Home Points

- SCAD is a separation of the coronary arterial walls that often leads to ACS in the absence of atherosclerosis or trauma.

- While seldom diagnosed, it is associated with cardiac arrest in the young, particularly females in the peripartum period.

- Fortunately, most patients will have an elevated troponin with the ACS symptoms, leading to the same management.

- In suspected SCAD, P2Y12 anti-platelets should be avoided in the ED as it can preclude a patient’s eligibility for CABG.

References

- Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(19):e523-e557.

- Luo H, Liu B, Hu J, Wang X, Zhan S, Kong W. Hyperhomocysteinemia and MethylenetetrahydrofolateReductase Polymorphism in Cervical Artery Dissection: A Meta-Analysis. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2014;37(5):313-322.

- Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Association WithPredisposing Arteriopathies and Precipitating Stressors and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(5):645-55.

- Pezzini A, Del Zotto E, Archetti S, et al. Plasma Homocysteine Concentration, C677T MTHFR Genotype, and 844ins68bp CBS Genotype in Young Adults With Spontaneous Cervical Artery Dissection and Atherothrombotic Stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(3):664-669.

- Liang JJ, Skalski JH, Mankad R. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Is There a Metabolic Association?Perfusion. 2013;28(5):457-458.

- Pavlov M, Ćelap I. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor 1 in Acute Coronary Syndromes. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2019;491:52-58.

- Cheung C, Starovoytov A, Parsa A, et al. In-Hospital and Long-Term Outcomes Among Patients With Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Presenting With Ventricular Tachycardia and/or Fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;74(13):B46

- Jamme M, Ben Hadj Salem O, Guillemet L, et al. Severe Metabolic Acidosis After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Risk Factors and Association With Outcome. Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):62.

- Carr, C, Carson K, Millin M. Acidemia Detected on Venous Blood Gas After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Predicts Likelihood to Survive to Hospital Discharge. Journal of Emergency Medicine.2020;59(4):e105-e111.