Spinal cord ischemia is a rare cause of paraplegia, with spinal infarction accounting for only 0.3 – 1% of all strokes.1

Though many of the documented cases of spinal strokes have occurred in the setting of acute aortic pathology or aortic surgery, the majority of spinal strokes (86%) are spontaneous.2,5 Risk factors include atherosclerosis, degenerative disease, cardiac emboli, hypotension, and intercostal nerve blocks.7 Most cases have been seen in young women, though there is not a strong correlation.1

Clinical presentation can be explained by the anatomy of the vessels supplying the spinal cord. The vasculature of the spine has great variation, but always involves the anterior spinal artery (ASA) as the dominant blood supply followed by two posterior spinal arteries (PSA). Additional branches of the aorta perfuse the spine depending on the vertebral level, which can be divided into 4 distinct territories. C1 to T3 receives supply from the vertebral arteries, T3 to T7 is often supplied by branches of the intercostal arteries, T8 to T12 (and sometimes the conus medullarus) receives blood by the major radicular artery of Adamkiewicz (AA), and the conus sometimes receives supply from the iliac branches.2,5

Spinal cord infarction is infrequent and if missed can result in significant mortality, disability (including irreversible paralysis), and reduced quality of life.2 Here we discuss a case of spinal stroke in an undifferentiated patient.

Case

A 48-year-old female was transferred from an outside hospital with concern for numbness, paresthesias, and weakness of the bilateral lower extremities. The patient had a past medical history of chronic abdominal pain and opiate use disorder. She reported IV drug use within the prior 2 weeks. She said had snorted fentanyl, taken a nap, and woke with inability to move her lower extremities before going to the hospital. She reported a progressive history of weakness in her legs for several weeks leading up to this event. She denied fever, chills, saddle anesthesia, and urinary or fecal incontinence. She denied tick exposures. Of note, the patient had a recent admission (10 days prior) for generalized fatigue and weight loss. At that time, imaging demonstrated possible bilateral renal infarcts. She left the hospital against medical advice before completion of her workup.

On exam, she was alert with vital signs of: T 98.5℉, P 112, R 16, and BP 154/104. There was no cardiac murmur. Neurologic exam showed lower extremity strength of 1/5 hip flexion/extension, 0/5 knee flexion/extension, 0/5 dorsi-/plantarflexion bilaterally. Patellar and Achilles reflexes remained intact and she had a negative Babinski. Rectal tone was absent. She denied midline spinal tenderness. Sensation was intact throughout her lower extremities. The rest of the physical exam was non-contributory.

Laboratory studies revealed a leukocytosis of 18.2, hyponatremia of 122, and hypokalemia of 3.0. Inflammatory markers were also elevated with a CRP of 174.7 and ESR of 95. Bedside ECHO was concerning for vegetation. The patient met sepsis criteria with probable cardiac or spinal sources, including endocarditis with emboli and spinal abscess, and empiric antibiotics and fluids were initiated.

MRI did not show evidence of spinal epidural abscess or discitis/osteomyelitis, but it was suggestive of infarction secondary to occlusion of the anterior spinal artery.

She was admitted for further workup and treatment.

Discussion

This patient presented with symptoms consistent with cauda equina syndrome. Though it is classically taught that cauda equina syndrome is caused by compressive lesions, such as disc herniation, epidural abscess, tumor, hematoma, canal stenosis, there are a number of non-compressive causes, including discitis, trauma, and aortic obstruction.4 Typical symptoms of cauda equina syndrome include lower back pain, fever, saddle anesthesia, fecal or urinary incontinence or retention, and lower extremity weakness or paralysis. Often, subtleties on history or exam can point toward the correct etiology.

Diagnosis

In this case, the patient’s history of IV drug use and that she met SIRS criteria (tachycardia, leukocytosis) initially prompted concern for spinal epidural abscess. However, the clue that suggested spinal stroke of the anterior spinal artery instead of epidural abscess was the preservation of sensation on physical exam. This is because occlusion of the anterior spinal artery, which supplies the anterior portion of the spinal cord, would cause loss of function of the corticospinal (motor) tract but would spare the sensory tracts of light touch and proprioception.

It is important to note that the clinical presentation of spinal infarction varies based on the involved vessel and vertebral level. Patients can present with acute painless paraplegia, bowel and bladder dysfunction, loss of pain and temperature sense, but typically have preserved proprioception, vibration, and sensation to light touch.3,6 In contrast, spinal epidural abscesses typically present with hypoesthesia secondary to local ischemia from direct compression of the spinal vasculature or via septic thrombophlebitis.3

Ultimately, MRI with contrast is the gold standard diagnostic test for both spinal infarctions and spinal epidural abscesses.1,3 It should be obtained emergently if either condition is on the differential.

Take-Home Point

It is important to consider spinal infarction in the differential for back pain with neurologic deficits, as prompt recognition can improve patient outcomes, prevent long-term disability, and maintain quality of life.

IMAGES

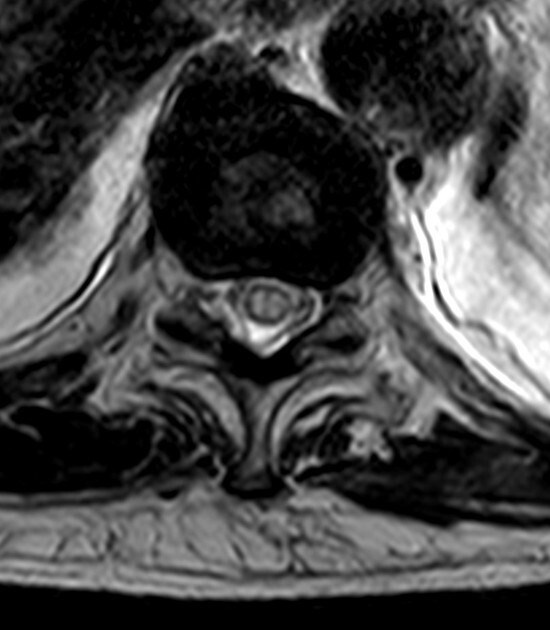

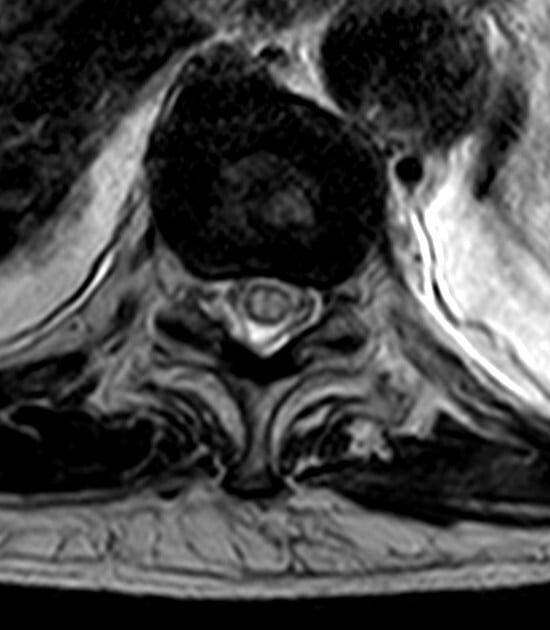

Reproduced from a case courtesy of Dr. Vincent Tatco, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 45707, these MRI images demonstrate changes seen in a different patient with spinal cord ischemia due to aortic dissection. The sagittal views of T2-weighted and STIR sequences reveal a pencil-shaped area of increased signal in the intramedullary spinal cord from T8-T9 to the conus medullaris. The axial views of T2-weighted MRIs may exhibit an owl’s eye appearance where the patient has high signals in the anterior horn cells bilaterally.

.

.

References

- Romi F, Naess H. Spinal Cord Infarction in Clinical Neurology: A Review of Characteristics and Long-Term Prognosis in Comparison to Cerebral Infarction. Eur Neurol. 2016;76(3-4):95-98.

- Caton MT, Huff JS. Spinal Cord Ischemia. [Updated 2020 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Rosc-Bereza K, Arkuszewski M, Ciach-Wysocka E, Boczarska-Jedynak M. Spinal epidural abscess: common symptoms of an emergency condition. A case report. Neuroradiol J. 2013 Aug;26(4):464-8.

- Rider LS, Marra EM. Cauda Equina And Conus Medullaris Syndromes. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan.

- Romi F, Naess H: Characteristics of spinal cord stroke in clinical neurology. Eur Neurol. 2011;66:305-309.

- El-Osta B, Ghoz A, Singh VK, Saed E, Abdunabi M. Spontaneous spinal cord infarction secondary to embolism from an aortic aneurysm mimicking as cauda equina due to disc prolapse: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7460.