Although initially described in the setting of military exercises (reported prevalence around 1.8%), SIPE has been increasingly described in the setting of triathlons and other competitive swimming events.1-3 Despite its potentially deleterious effects, SIPE continues to be an understudied phenomenon with an unknown true prevalence.4

Case Report

A 61-year-old male triathlete with a past medical history of coronary artery disease, requiring percutaneous coronary intervention 2 years prior, presents to the Ironman medical tent in severe respiratory distress. After swimming approximately 100 meters, he began experiencing palpitations, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis. During this time, the patient’s smart watch recorded a heart rate of 243 bpm.

Initial vitals are notable for a blood pressure of 264/136 mmHg, a heart rate of 130 bmp, a respiratory rate of 32 bpm, and an oxygen saturation of 82% on room air.

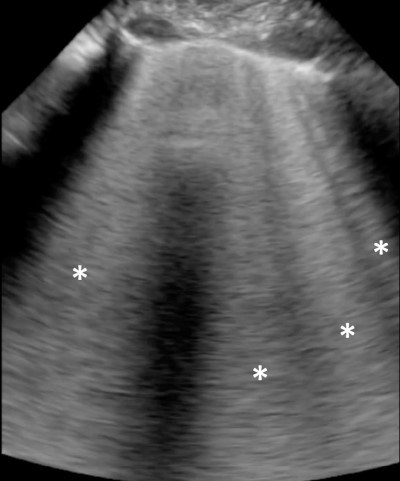

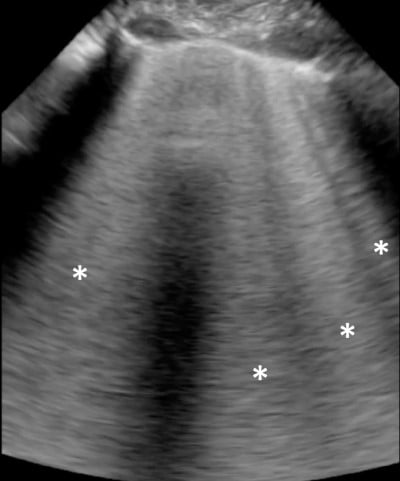

Physical exam is notable for respiratory distress, coarse breath sounds, and hemoptysis. POCUS of the lungs reveals confluent B-lines, consistent with significant pulmonary edema.2

Cardiac ultrasound is grossly unremarkable, with a normal ejection fraction, no wall motion abnormalities, and a collapsible IVC.

Given the findings on ultrasound, as well as the patient’s clinical presentation, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema secondary to SIPE was suspected.

Image 1. Lung window obtained with portable ultrasound device showing confluent B-lines (asterisk)

Discussion

Swimming-induced pulmonary edema is an exceptionally rare—and not particularly well-understood—condition. The pathophysiology of SIPE is multifactorial. Research suggests that water submersion increases compressive forces on the body’s peripheral capacitance vessels, resulting in the redistribution of blood to the thoracic cavity with subsequent increases in venous return and ventricular preload.5 Interestingly, this hemodynamic shift is further augmented by the tight-fitting neoprene wetsuits often worn by triathletes and divers, sometimes increasing central venous pressure by 12-18 mmHg and stroke volume by 25%.6,7

Thermal stressors may also contribute to SIPE. Cold water submersion has been found to increase blood pressure and sympathetic tone, leading to increased left ventricular end diastolic volume pressures.8,9 These physiologic changes ultimately result in dysregulated pulmonary artery pressures (MPAP) and pulmonary artery wedge pressures (PAWP).6 These elevated intrathoracic and hydrostatic pressures have also been shown to cause micro-perforations in the alveolar blood-gas barrier, a plausible explanation for the high rates of hemoptysis seen in SIPE.11

Management

Currently, there is no standard standardized treatment algorithm for SIPE. Therefore, clinicians are recommended to tailor medical management to the pathophysiological processes believed to cause SIPE.

- Prehospital management: As soon as there is concern for SIPE, the patient should be immediately removed from the water and placed in a warm environment.12 The constrictive neoprene suit should be removed.

Once all environmental factors have been addressed, supportive care and symptomatic treatment can begin. A recent study demonstrated the utility of CPAP or PEP to reverse hypoxia in SIPE.13 Other medications such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, diuretics, and nitric oxide have been discussed in case reports. At present, however, there are no large studies supporting their utility.

Some data suggests the use of inhaled β2-agonist to assist in alveolar fluid absorption; however, clinicians should take caution, as such medication can potentiate further androgenic activation. From a prophylactic standpoint, there is anecdotal evidence of vasodilators, such as sildenafil and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, preventing SIPE in certain patient populations.14

Case Conclusion

An attempt was made to stabilize the patient with high-flow oxygen and sublingual nitroglycerine; however, the patient’s symptoms persisted. It was decided to escalate care by placing the patient on BiPAP and a nitroglycerine drip. Within minutes, the patient’s symptoms began to improve, and he was subsequently transported to the hospital.

While in the ED, a CTA chest was obtained, revealing bilateral parenchymal ground glass opacities, consistent with pulmonary edema, leading to subsequent admission to a telemetry unit for further symptomatic management. The patient was discharged a day later with cardiology follow-up and no residual symptoms.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- SIPE continues to be an understudied and underdiagnosed phenomenon that should be considered in athletes presenting with respiratory distress and pulmonary edema during or after competing in swimming events.

- In the prehospital setting, as soon as SIPE is suspected, any neoprene or tight-fitting gear should be removed, and the patient should be removed from the cold environment and kept warm.

- Most cases resolve within 48 hours, and management is primarily supportive care.

References

- Weiler-Ravell D, Shupak A, Goldenberg I, et al. Pulmonary oedema and haemoptysis induced by strenuous swimming. BMJ. 1995;311:361.

- Grünig H, Nikolaidis PT, Moon RE, Knechtle B. Diagnosis of Swimming Induced Pulmonary Edema-A Review. Front Physiol. 2017;8:652.

- Kumar M, Thompson PD. A literature review of immersion pulmonary edema. Phys Sportsmed. 2018;47(2):148-151.

- Shupak A, Weiler-Ravell D, Adir Y, Daskalovic YI, Ramon Y, Kerem D. Pulmonary oedema induced by strenuous swimming: a field study. Respir Physiol. 2000;121:25-31.

- Boccatonda A, Cocco G, D'Ardes D, Vicari S, Schiavone C. All B-lines are equal, but some B-lines are more equal than others. J Ultrasound. 2023;26(1):255-260.

- Epstein M. Renal effects of head-out water immersion in man: implications for an understanding of volume homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 1978;58:529-81.

- Arborelius M Jr, Ballidin UI, Lija B, Lundgren CE. Hemodynamic changes in man during immersion with the head above water. Aerosp Med. 1972;43:592-8.

- Lazar JM, Khanna N, Chesler R, Salciccioli L. Swimming and the heart. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:19-26.

- Sramek P, Simeckova M, Jansky L, Savlikova J, Vybiral S. Human physiological responses to immersion into water of different temperatures. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;81:436-42.

- Park KS, Choi JK, Park YS. Cardiovascular regulation during water immersion. Appl Human Sci. 1999;18:233-41.

- Wester TE, Cherry AD, Pollock NW, et al. Effects of head and body cooling on hemodynamics during immersed prone exercise at 1 ATA. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:691-700.

- West JB, Tsukimoto K, Mathieu-Costello O, Prediletto R. Stress failure in pulmonary capillaries. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:1731-42.

- Shah A, Baggish A. Swimming-Induced Pulmonary Edema – American College of Cardiology. Cardiology. 2018.

- Seiler C, Kristiansson L, Klingberg C, et al. Swimming-Induced Pulmonary Edema: Evaluation of Prehospital Treatment With CPAP or Positive Expiratory Pressure Device. Chest. 2022;162(2):410-420.

- Moon RE, Martina SD, Peacher DF, et al. Swimming-induced pulmonary edema: pathophysiology and risk reduction with sildenafil. Circulation. 2016;133:988-96.