A 65-year-old female presented to the ED for evaluation of generalized weakness and hyperglycemia following a syncopal episode.

The patient was seated in a chair while visiting another patient in the hospital when she suddenly had a syncopal episode without reported trauma. She denied experiencing any associated chest pain or shortness of breath. She reported nausea and vomiting following the event, as well as malaise and diarrhea in the days prior to the event. She said her blood glucose had been poorly controlled in the past week. She denied any recent fevers or chills.

Her extensive medical history included coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure with depressed ejection fraction and bi-ventricular implantable cardiac defibrillator, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, depression, and tobacco abuse. She had multiple prescribed medications, notably including hydrochlorothiazide and furosemide.

Vitals on initial presentation were unremarkable, and the patient was afebrile. Other than appearing generally ill with intermittent non-bloody vomiting, the patient’s physical examination was unremarkable.

During the initial evaluation, the patient began having rigid, convulsive body movements and became unresponsive with snoring respirations. Cardiac telemetry monitoring showed ventricular tachycardia. The patient’s implanted cardiac defibrillator delivered a shock, leading to resolution of the ventricular tachycardia, and the patient immediately became alert and oriented. Ventricular tachycardia with subsequent ICD activation occurred several more times over the next 30 minutes.

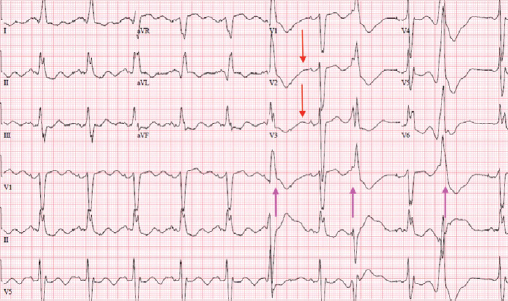

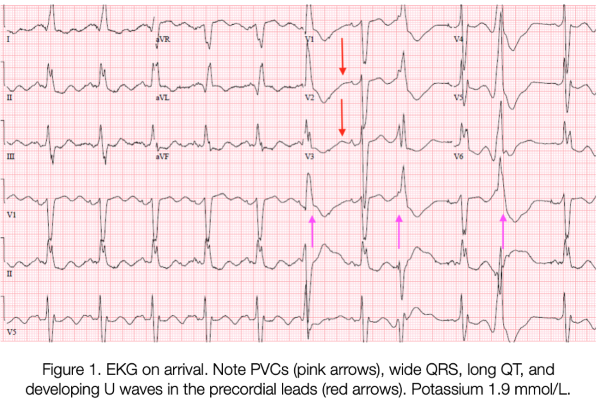

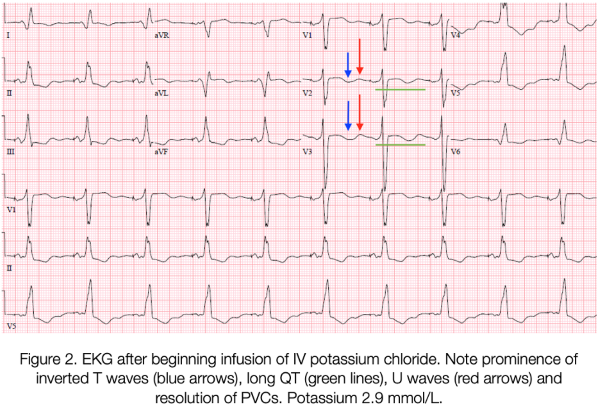

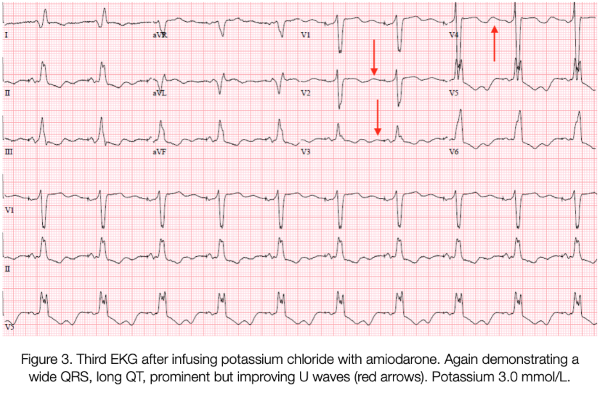

Serial ECGs (Figures 1-3) showed inverted T-waves, wide QRS complexes, and prominent U-waves with frequent premature ventricular contractions. Point of care laboratory testing revealed: K 1.9 mmol/L, Mg 2.4 mg/dL, glucose 440 mg/dL.

Intravenous potassium was started immediately; she received 70 mEq total in the ED. An amiodarone bolus followed by infusion was also provided. The patient continued to experience several more episodes of unstable ventricular tachycardia and resolution with ICD activation. Emergent central access was obtained via femoral central venous catheter, and the patient was intubated without complications to ensure airway protection during recurrent defibrillation. Serial laboratory tests showed incremental improvement of hypokalemia, with appropriate stabilization of the patient’s myocardial irritability and normalization of her ECG. This patient was admitted to the ICU and extubated the next day.

Cardiac electrophysiology was consulted for ICD interrogation and found that the patient had 14 defibrillation events in total in the ED; 7 were triggered by ventricular tachycardia and 7 were ventricular fibrillation. Additionally, electrophysiology noted the patient had an ICD discharge on each of the 2 days prior to her ED episode.

It was determined that the patient's severe hypokalemia was likely precipitated by a combination of factors: the use of hydrochlorothiazide and furosemide, several days of poor oral intake, diarrhea, and vomiting. The inpatient team discharged the patient 6 days after admission with discontinuation of hydrochlorothiazide and the addition of amlodipine for hypertension control.

Clinical Manifestations of Severe Hypokalemia

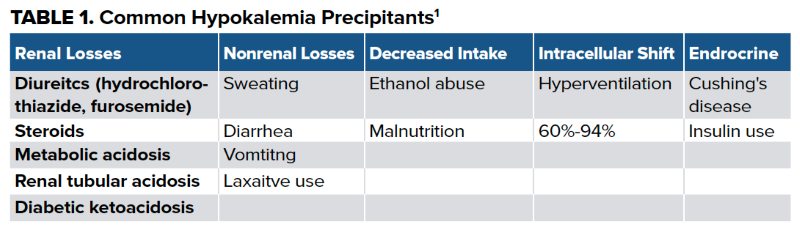

Hypokalemia can be precipitated by a number of factors (Table 1). Severe hypokalemia can present similarly to hyperkalemia; therefore, a thorough history is paramount. When serum potassium levels fall below 2.5 mEq/L, patients may experience severe muscle weakness, muscle cramping, and even rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria.1 If rhabdomyolysis is present, intracellular potassium is released and may mask the severity of the underlying overall hypokalemia.

Additionally, patients may experience respiratory muscle weakness that may lead to respiratory failure, as well as vomiting and diarrhea that will potentiate further potassium losses.2

As seen in this case, severe hypokalemia can result in life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Consider hypokalemia if EKG findings include premature atrial contractions, premature ventricular contractions, sinus bradycardia, atrioventricular blocks, ventricular tachycardia, or ventricular fibrillation.3

Several EKG manifestations are characteristic of hypokalemia. Early EKG changes may include increased amplitude and width of P-waves, PR segment prolongation, T-wave flattening and inversion, ST-segment depression, prominent U waves in the lateral precordial leads. There may also be an "apparent" long QT resulting from the fusion of the T and U waves, termed "long QU."3 Be alert for concomitant hypomagnesemia in patients with hypokalemia. Patients with both hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia have an increased risk of developing polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.2

Severe Hypokalemia Treatment

The treatment of hypokalemia consists of several strategies that may be utilized depending on the chronicity and severity of the disturbance. The following treatments are intended for acute life-threatening hypokalemia when serum levels fall below 2.5mEq/L or if patients are symptomatic.

In the setting of severe, life-threatening hypokalemia, IV potassium repletion should be initiated. Oral repletion may be considered as an adjunct if the patient can tolerate oral medications, however systemic absorption is slower.

Potassium chloride (KCl) is the preferred choice for IV repletion as it has faster onset than potassium bicarbonate. KCl should be administered in an isotonic saline solution without dextrose. The use of dextrose-containing fluids will prompt an insulin release, driving potassium into the cells resulting in further reduction of serum potassium levels.2

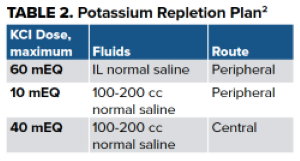

Patients with life-threatening hypokalemia secondary to GI losses, as in this case, should have potassium repleted between 10-40 mEq/hr.1 This can be accomplished in several ways (Table 2).

It is important to be mindful of potential complications and risks associated with potassium infusions. Pain at the site of infusion and phlebitis occurs typically at rates >10 mEq/hr when run peripherally. When faster rates or higher doses are needed, central vascular access should be obtained.

Infusing large amounts of potassium can inadvertently result in severe hyperkalemia. Caution should be taken, especially in patients with acute or chronic renal dysfunction. Normal serum potassium in the extracellular space is 50-70 mEq; rapid infusions of 40-60 mEq can result in serum concentrations that exceed safe levels. Therefore, close cardiac monitoring as well as serum potassium level checks every 2-4 hours are recommended. Repletion should be continued until serum potassium concentrations are consistently above 3-3.5 mEq/L and symptoms related to hypokalemia have resolved. At that time, dosing may be reduced, typically after the patient has already been admitted. Depending on the severity of hypokalemia, admission to a critical care service should be considered, especially if there is any indication of hemodynamic instability or if the patient will need close cardiac monitoring.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Consider hypokalemia when faced with unstable cardiac rhythms.

- EKG findings indicative of hypokalemia:

- Long PR

- Flattened or inverted T-waves

- ST depression

- U-waves

- T and U wave fusion resulting in long QU

- Hypokalemia with hypomagnesemia increases the risk of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

- Treat with 10-40 mEq/hr IV KCI in isotonic fluids WITHOUT dextrose.

References

- Pfennig CL, Stovis CM. Chapter 117: Electrolyte Emergencies. In Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Ed. Walls RM, Hockberger RM, Gausche-Hill M. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1519-1520.

- Mount D. Clinical manifestations and treatment of hypokalemia in adults. UpToDate. Current through 2/2021. Accessed 3/2021.

- Burns E. LifeInTheFastlane. Hypokalemia EKG Changes. 2/7/2021. Accessed 3/2021.