This is a unique case of Lemierre's syndrome in a person who injects drugs (PWID) without a history of recent oropharyngeal infection or the presence of a central venous catheter.

Lemierre' syndrome is defined as internal jugular vein septic thrombophlebitis, typically preceded by pharyngitis or the presence of a central venous catheter. It is a disease that was more prevalent in the 20th century, however, presentations have declined as a result of the discovery and widespread use of antibiotics. We report a unique case of Lemierre’s syndrome in a person who injects drugs (PWID) without a history of recent oropharyngeal infection or the presence of a central venous catheter.

Background

Septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, or Lemierre's Syndrome, is a diagnosis that is rarely encountered today. Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for this potential disease state as delay or outright failure to detect and treat it appropriately sharply increases morbidity and mortality. This condition most often presents as the sequelae of bacterial pharyngitis but other etiologies have been reported. Affected individuals typically exhibit systemic signs of infection such as fevers and/or rigors. Nearly all patients will have positive blood cultures. The most commonly isolated bacterium isolated is Fusobacterium necrophorum, though others such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species have been implicated. Nearly all patients with Lemierre's syndrome will also have findings concerning for septic emboli.1 The discovery and widespread implementation of antibiotics in the early 20th century has been pivotal in decreasing the number of cases seen today. Nevertheless, Lemierre's Syndrome remains a relevant disease today as rare cases still do occur. One such case will be discussed in this presentation.

Case

A 52-year-old female with a past medical history of untreated hepatitis C virus, intravenous opiate use disorder, alcohol use disorder, and COPD presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of fever, altered mental status and an open left neck wound. The wound was located in an area where the patient frequently injected heroin and fentanyl into her external jugular vein.

On initial evaluation, the patient's vital signs were T 39.6C (103.2F), HR 205, BP 124/73mmHg, RR 28, and SPO2 89% on room air. The patient was placed on supplemental O2 and an electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained revealing supraventricular tachycardia. The patient was given adenosine 6 mg IV push with successful conversion to sinus tachycardia. Examination revealed a large left-sided neck wound with copious purulent drainage as well as a left postauricular wound (Figure 1). Despite the patient's high acuity, there was a lack of leukocytosis or lactic acidosis.

Figure 1.

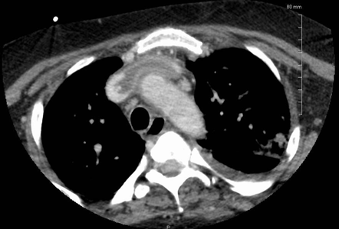

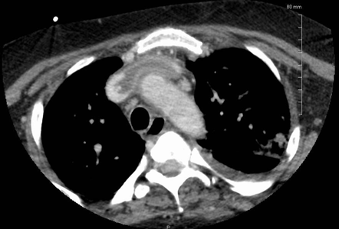

Intravenous fluid resuscitation as well as broad spectrum antibiotics, vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam, were initiated early in the course of the patient's management. Despite these measures, the patient became hypotensive requiring central venous catheter placement and vasopressor support. With these measures, the patient's hemodynamic parameters improved. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans (CT) of the neck and chest were subsequently obtained, revealing a 12 cm area of superficial and deep soft tissue swelling involving the left neck, extensive deep vein thrombosis (DVT) extending from the internal jugular vein to the superior vena cava, innumerable heterogeneous pulmonary nodules/opacities and mediastinal stranding worrisome for mediastinitis (Figure 2, Figure 3).

After stabilization in the ED, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management. On the evening of admission, the patient developed worsening respiratory distress which ultimately necessitated endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. The vascular surgery service was then consulted and recommended heparin infusion due to the large size of the left intrajugular thrombus. Otolaryngology was also consulted, who performed a bedside incision and drainage of the neck abscess, followed by an intraoperative wound washout and rotational skin flap procedure.

Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus mitis and wound cultures revealed Streptococcus viridans, for which the infectious disease service recommended treatment with vancomycin, cefepime, and clindamycin. The patient remained on mechanical ventilation for several days and was successfully extubated on hospital day 8. She was subsequently downgraded to the intermediate care unit on hospital day 10 where her care was continued. On hospital day 17, the patient was found to have anisocoria, left upper extremity pronator drift, and right-sided tongue deviation. Emergent CT scan of the brain was obtained and revealed an acute right lentiform nucleus parenchymal hematoma with surrounding vasogenic edema. The neurosurgery service was consulted and recommended non-surgical management. Follow up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a hemorrhagic mass with surrounding vasogenic edema in the right basal ganglia with ring enhancement as well as multiple additional ring enhancing lesions within the brain. These findings were concerning for an infectious process, likely septic emboli. Due to this, the patient's anticoagulation was reversed and she was again upgraded to the ICU. After several days, the patient’s neurologic symptoms improved and she was subsequently discharged to a subacute rehabilitation center.

Discussion

Lemierre's syndrome is a unique condition defined by septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. Historically, this condition has been preceded by oropharyngeal infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum as the most common bacterium. More recently, however, drug resistant pathogens such as methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have been reported, particularly in PWID and those with HIV. In PWID, superficial distal veins can become damaged or scarred due to repeated injection. As a result, attempts are often made to access more proximal or central vessels. Access to these sites can result in direct inoculation of bacteria into the skin and vasculature, predisposing the individual to bacteremia and subsequent septic thrombophlebitis.2 Skin flora such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species are common causes of these infections. Oral flora such as Fusobacterium necrophorum can be introduced to the site when PWID lubricate needles with saliva, and various mixing agents can predispose PWID to atypical pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cepacia, and fungal species.2

The diagnosis is typically made with computed tomography (CT) imaging as it is readily available. Ultrasonography can also be used but visualization is often impaired by bony structures such as the mandible or clavicle.1 If internal jugular vein thrombosis is an incidental finding on imaging, it is important to take the patients clinical context into consideration, as imaging alone cannot reliably distinguish between septic and non-septic thrombophlebitis.

Prompt antibiotic treatment should be provided to those with high clinical suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome and those with confirmed diagnosis. Initial treatment should include either a beta-lactamase resistant beta-lactam, such as piperacillin/tazobactam, or a carbapenem. Vancomycin should be added to those at risk for catheter associated septic thrombophlebitis or those at risk for MRSA infection. Previous reviews have found a wide range of treatment duration, but the mean duration is 4 weeks, including 2 weeks of intravenous antibiotics followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics.1

The role of anticoagulation in the treatment of Lemierre’s syndrome remains controversial as there are no controlled studies on this topic. Previous reviews have shown that 21-23% of patients are treated with anticoagulation with treatment duration varying between 2 weeks and 6 months. Factors such as thrombus extension and risk of bleeding often impact this decision, but further studies are needed to clarify the role of anticoagulation in these patients.1

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Although relatively rare, Lemierre’s syndrome should be suspected in patients with a preceding oropharyngeal infection, septic emboli and in those with evidence of proximal or central vein access.

- People who inject drugs are at increased risk for serious infections due to direct bacterial inoculation. Atypical pathogens should be suspected in individuals who lubricate needles with saliva or use mixing agents.

- Prompt diagnosis and antibiotic administration will result in decreased morbidity and mortality.

- The role of anticoagulation remains controversial.

REFERENCES

- Johannesen K, Bodtger U. Lemierre’s syndrome: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;Volume 9:221-227.

- Dimitropoulou D, Lagadinou M, Papayiannis T, et al. Septic Thrombophlebitis Caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum in an Intravenous Drug User. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2013;2013:870846.

Correia MS, Sadler C. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Septic Internal Jugular Thrombophlebitis: Updates in the Etiology and Treatment of Lemierre’s Syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(6):709-712.