An ectopic pregnancy (EP) is synonymous with extrauterine pregnancy that signifies implantation of a developing blastocyst outside the endometrial cavity, where normal implantation and development should occur.1

While modern technology and advancements make diagnosing and treating this pathology more efficient, EPs are not a new phenomenon, with the first documented case occurring by the surgeon Albucasis in 963 AD.1

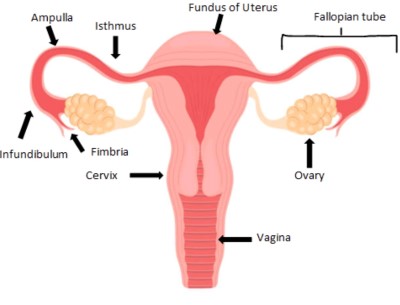

EPs occur in approximately 2% of pregnancies in the United States.2 About 95% of EPs occur in the fallopian tubes.1Most EPs can be located to the ampullary portion of the fallopian tubes rather than the fimbria or isthmus.1Unfortunately, EPs located in the fallopian tubes pose the greatest risk for maternal death and morbidity.2

Ultrasound is a primary tool in the evaluation and management of EPs. Ultrasound coupled with β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β -hCG) are the standard of care in the workup of EP, with an expected doubling of β -hCG in 48 hours.2

Despite significant improvements in techniques for early diagnosis and management of EP, research and case reports remain crucial, as the incidence of EP has increased sixfold in the past 25 years, affecting more than 100,000 patients each year.3 Some reasons for the increase include higher prevalence of risk factors such as sexually transmitted infections leading to pelvic inflammatory disease, intrauterine device use, pelvic surgeries including tubal ligation, in vitro fertilization, and previous EP. Another explanation for increasing prevalence is improvement in diagnosis, advancement in technologies such as laparoscopy, and improved ultrasound techniques, which lead to more diagnoses. Also, the recent trend of women having children later in life, when the risk of EP is highest, has contributed to increased prevalence.3

Case Report

A 28-year-old female with a past medical history of polycystic ovarian syndrome presented to the emergency department with acute abdominal pain, lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting, and syncope. The pain started about 1 week prior to presentation and worsened 3 days prior to initial evaluation. The patient had an unknown last menstrual period, but stated she was spotting the day of her ED encounter. She was sexually active and did not use any form of contraception.

Upon her arrival at the ED, she was noted to be pale in appearance and hypotensive. Her first set of vital signs included blood pressure 87/49, heart rate 75, respiratory rate 33, and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Her physical exam demonstrated a patient who was in acute distress, ill-appearing, diaphoretic, and pale. The exam also demonstrated dry mucous membranes and an abdomen that was soft but diffusely tender. Point-of-care (POC) labs were urgently collected, and an ultrasound was obtained within minutes of the patient’s arrival due to concern for ruptured EP versus hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst.

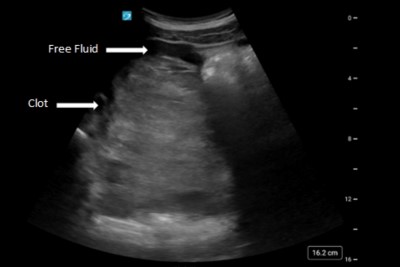

POC labs demonstrated a hemoglobin of 6.2, hematocrit of 18.2, and RBC of 2.11. A type and screen was collected, and 2 units of emergency release blood were given. Her quantitative β -hCG turned out to be 12,098. The bedside transabdominal ultrasound was obtained and demonstrated a massive amount of free fluid in the pelvis with suspicion for clot surrounding the uterus. There was free fluid in the upper quadrants of the abdomen with no visible intrauterine pregnancy in the uterus.

The obstetrics and gynecology attending was contacted emergently to evaluate the patient and ultimately decided this patient was appropriate for the operating room (OR). Her preoperative diagnosis included hemoperitoneum, suspected ruptured EP, and anemia. The postoperative diagnosis was a ruptured right EP. In the OR, a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed with a right salpingectomy. There were approximately 3.3 liters of blood and clots in the abdomen upon entry, but minimal bleeding during the actual procedure.

After the operation was performed, the patient’s POC hemoglobin was 9.2, so 1 unit of plasma was given. By post-op day 1, the patient was meeting all post-operative goals. She was ambulating, voiding without difficulty, and tolerating oral intake. She was discharged home in stable condition. She was seen 2 weeks after discharge and seemed to be doing well without complications, including no vaginal bleeding and a stable hemoglobin of 12.0.

The pathology report for the right fallopian tube described the specimen as a disrupted fallopian tube measuring 5.5 cm in length by up to 2.0 cm in diameter, with a fimbriated end. The serosal surface was purple-tan and smooth with a full-thickness disruption and protruding red-tan and spongy soft tissue admixed with clotted blood. Sectioning revealed a moderately dilated lumen containing spongy red-tan soft tissue admixed with clotted blood. No true fetal parts were grossly identified.

Discussion

When a female of reproductive age comes to the ED presenting with nonspecific symptoms including lower abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, syncope, or weakness, EP needs to remain on the differential.4 Despite advancement in modern medicine, the rate of EPs is approximately 15% in Western countries, with a retrospective study showing an increased rupture rate during the COVID-19 pandemic.5,6 The rise in rupture rate during the pandemic is thought to be due to delay in presentation to the ED, with 1 retrospective cohort study demonstrating that more women presented with sonographic evidence of high fluid volume in the abdomen than prior to the pandemic.5

While some EPs can be treated with medication, some develop long enough without early diagnosis to the point of rupture, which then needs to be addressed surgically. Usually, an EP grows up to 1.5-3.5cm, and any size greater than this will lead to rupture.

This case reports an EP that measured 5.5 cm by 2 cm and ultimately ruptured. This stresses the importance of securing the diagnosis early prior to development into a size with potential to rupture.7

The current standard for diagnostics includes ultrasound imaging coupled with β-hCG level monitoring. With ultrasound becoming more advanced, it is important to be aware of the typical features that can be found with ultrasound. Some features include presence of a pseudo-gestational sac, thickened endometrium, fluid in the posterior cul-de-sac, and the tubal ring sign.4

Occasionally, an EP with chronic insidious bleeding will appear as an organized, expansive clot on ultrasound, as seen in this case report.2 Another case report of a 17-week gestational age fetus also demonstrated this finding of clotted blood in the patient’s abdomen.7 Although a scant amount of intraperitoneal fluid can be normal, significant intra-abdominal fluid raises the suspicion for hemoperitoneum, which was also seen in this case report.2 One interesting publication found that ED patients with a ruptured EP who received a POCUS first had shorter times to diagnosis, obstetric consultation, and OR arrival compared with those who received radiology department-performed ultrasound, stressing the importance of obtaining the ultrasound fast in the emergency department.8 In this case report, the ultrasound was at bedside by almost the same time that IV access was obtained.

Conclusion

EPs are the leading cause of maternal mortality within the first trimester of pregnancy.5 The standard of care for workup and diagnosis of EPs includes a quantitative β-hCG and ultrasound imaging. Several studies, including this case report, emphasize the importance of ultrasound utilization in the quick diagnosis and management of EPs. This case demonstrates a ruptured ectopic in a patient who was able to be safely discharged 1 day post-operation, after emergency physicians were able to quickly diagnose with ultrasound at bedside and get the obstetrics team to take the patient to the OR in a timely manner.

References

- Marion LL, Meeks GR. Ectopic pregnancy: History, incidence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(2):376-386. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182516d7b

- Scibetta EW, Han CS. Ultrasound in Early Pregnancy: Viability, Unknown Locations, and Ectopic Pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019;46(4):783-795. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2019.07.013

- Carr RJ, Evans P. Ectopic pregnancy. Prim Care. 2000;27(1):169-183. doi:10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70154-8

- Stremick JK, Couperus K, Ashworth SW. Ruptured Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy at Fifteen Weeks Gestational Age. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(1):62-64. Published 2019 Jan 29. doi:10.5811/cpcem.2019.1.40860

- Mullany K, Minneci M, Monjazeb R, C Coiado O. Overview of ectopic pregnancy diagnosis, management, and innovation. Womens Health (Lond). 2023;19:17455057231160349. doi:10.1177/17455057231160349

- Tulandi, T. Ectopic pregnancy: Epidemiology, risk factors, and anatomic sites. Waltham, MA. UpToDate; 2023.

- Shabbir U, Anwar J, Asghar MS, Zaman BS, Afzal A, Nadeem M. A ruptured seventeen weeks' ectopic pregnancy: A case report. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(2(B)):763-765. doi:10.47391/JPMA.10-1181

- Urquhart S, Barnes M, Flannigan M. Comparing Time to Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy Based on Type of Ultrasound Performed: A Retrospective Inquiry. J Emerg Med. 2022;62(2):200-206. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.07.064