A 65-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer is brought to the emergency department with one day of left leg swelling, followed by the development of severe pain and discoloration today. Vitals signs are remarkable only for tachycardia with a HR of 110. Physical examination shows a tense, edematous, tender left leg with mottling and cyanosis. Bedside ultrasound reveals no compression of the left common femoral, saphenous, or popliteal veins. What are your next steps in management?

Introduction

Phlegmasia alba and cerulea dolens are rare diseases along a spectrum of deep venous thromboses. Phlegmasia alba dolens, which translates to “painful white inflammation,” occurs when venous thrombosis progresses to a massive occlusion of the major deep venous system of the leg, but without ischemia as collateral veins are still patent. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens translates to “painful blue inflammation” and is the next progression of the disease, characterized by complete thrombosis of the deep venous system, including the collateral circulation. This results in significant venous congestion, fluid sequestration, and worsening edema. Untreated, it will progress to venous gangrene and cause massive tissue death.1

The overall incidence of this disease process is not well documented, but it does occur more frequently in women, in the fifth and sixth decades of life, and in the left lower extremity compared to the right.2 Most patients have associated risk factors such as malignancy, hypercoagulable state, surgery, trauma, inferior vena cava filter placement, pregnancy, or May-Thurner syndrome. The most common risk factor is malignancy, which is seen in 20-40% of cases.3 May-Thurner syndrome results in venous thrombosis secondary to an exaggeration of normal anatomy in which the left common iliac vein is compressed by the overriding right common iliac artery. Similarly, in pregnancy, a gravid third trimester uterus can become large enough to compress the iliac vein against the pelvic rim and cause venous stasis.1

Clinical Features

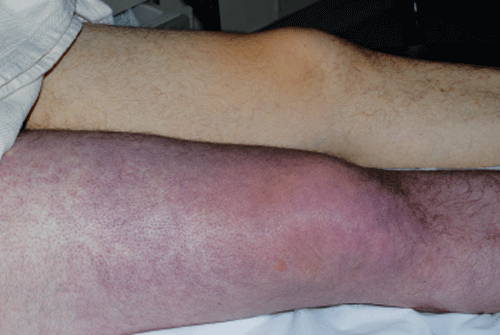

Symptoms occur 3-4 times more often in the left leg compared to the right leg, whereas upper extremity involvement is uncommon (<5%).2 Duration of symptoms can be gradual or sudden. Phlegmasia alba dolens presents as a triad of edema, pain, and white blanching skin without cyanosis. As the venous thrombosis progresses, it develops into phlegmasia cerulea dolens, which is characterized by edema, worsening pain, and cyanosis from ischemia. About 50% of the cases of phlegmasia cerulea dolens are not preceded by phlegmasia alba dolens.1 The cyanosis begins distally and progresses proximally as ischemia worsens. This process can result in massive fluid sequestration and the development of skin bullae and blebs.4 Further progression results in venous gangrene when muscle ischemia becomes infarction. Compartment pressures will increase, and patients may even experience hypotensive shock because of fluid sequestration and a severe systemic inflammatory response.1

Evaluation

While contrast venography is commonly described in the literature, it is rife with complications such as contrast administration in patients that may have renal failure and incomplete imaging because of severe burden of disease. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) can identify the proximal and distal ends of venous thrombosis, but it is limited by time and motion artifact in patients with severe pain.5

Ultrasound is the best initial imaging method for suspected deep venous thrombosis and phlegmasia alba and cerulea dolens. Point-of-care bedside ultrasonography in the emergency department can be easily performed and is preferred in the critically ill patient.6 At this time, two-point compression ultrasonography as a diagnostic evaluation specifically for this purpose has not been studied, but would likely be highly sensitive and specific given that the entire disease spectrum is defined by the continuously propagating massive clot burden.

Management

The initiation of anticoagulation for deep venous thrombosis is standard and routine care. The management of phlegmasia alba dolens and mild cases of phlegmasia cerulea dolens includes initiation of heparin infusion, warfarin bridging, fluid resuscitation, and steep limb elevation. Low molecular weight heparins have not been effectively studied in the setting of phlegmasia alba or cerulea dolens.7

Decisions regarding management of more severe cases of phlegmasia cerulea dolens, however, are still evolving. Systemic or catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy, versus surgical or catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy, is still a topic of debate.4 While there are no current guidelines regarding the best method of intervention, it is widely accepted that medical management alone is insufficient and could result in amputation or death. These patients require emergent consultation with vascular surgery and/or interventional radiology, and should be started on heparin anticoagulation if there will be any delay in intervention (such as an inter-facility transfer).

Minimally invasive endovascular approaches may offer similar outcomes with less morbidity when compared to open surgery, but no studies have clearly identified superiority.8 Institutional resources and specialist expertise should determine management of phlegmasia cerulea dolens and venous gangrene. Even with aggressive intervention strategies, the overall amputation rates are 12-25% among those who survive.3

Pulmonary emboli are a common complication and should also be considered during evaluation and treatment. The overall mortality rate for phlegmasia cerulea dolens is 20-40% and pulmonary emboli are believed to be responsible for 30% of these deaths.4 Inferior vena cava filter placement is generally recommended, but there is a paucity of data for this as well.9

Patients may compound their clinical crisis if they develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). There is currently little guidance on the usage of alternative agents in this specific population. Danaparoid is no longer available in the U.S., and lepirudin has been discontinued by Bayer HealthCare. Data regarding the usage of direct thrombin inhibitors such as argatroban and bivalirudin, or indirect factor Xa inhibitors such as fondaparinux, are represented by only a few case series.10

Conclusion

Phlegmasia cerulea dolens and venous gangrene are rare but life- and limb-threatening disease entities that require timely evaluation, resuscitation and intervention. Diagnosis is often made clinically, but rapid point-of-care bedside ultrasound can be used as an adjunct. Timely anticoagulation and coordination with vascular surgeons and/or interventional radiologists is necessary, but strategies may evolve as more robust literature becomes available.

References

- Perkins JM, Magee TR, Galland RB. Phlegmasia caerulea dolens and venous gangrene. Br J Surg. 2005;83(1):19-23.

- Haimovici H. The ischemic forms of venous thrombosis, Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, Venous gangrene. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1965 Sep-Oct;5(6):Suppl:164-73.

- Onuoha CU. Phlegmasia Cerulea Dolens: A Rare Clinical Presentation. Am J Med. 2015 Sep;128(9):e27-8.

- Lessne ML, Bajwa J, Hong K. Fatal reperfusion injury after thrombolysis for phlegmasia cerulea dolens. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012 May;23(5):681-6.

- Madhusudhana S, Moore A, Moormeier JA. Current issues in the diagnosis and management of deep vein thrombosis. Mo Med. 2009 Jan-Feb;106(1):43-8; quiz 48-9.

- Bhatt S, Wehbe C, Dogra VS. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007 Sep;35(7):401-4.

- Hull RD, Raskob GE, Pineo GF, et al. Subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin compared with continuous intravenous heparin in the treatment of proximal-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1992 Apr 9;326(15):975-82.

- Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 Jan 7;379(9810):31-8.

- Rokni Yazdi H, Rostami N, Hakimian H, et al. Successful catheter-directed venous thrombolysis in an ankylosing spondylitis patient with phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Iran J Radiol. 2013 Jun;10(2):81-5.

- Filis K, Lagoudianakis EE, Pappas A, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and phlegmasia cerulea dolens of the upper limb successfully treated with fondaparinux. Acta Haematol. 2008;120(3):190-1.