Tuba City is an unincorporated town baked into the high desert of northern Arizona. With a population of 9,000, it is a major center of commerce, services, and administration for the surrounding Navajo Reservation. Having learned about the opportunity to rotate there, I spent one month working in the emergency department at Tuba City Regional Hospital (TCRH) in April 2017. Given the seasonal extremes of climate, spring seemed like an ideal time to go (it was).

Outside the ED at Tuba City Regional Hospital. (EMTALA doesn't apply to the local canines.)

Outside the ED at Tuba City Regional Hospital. (EMTALA doesn't apply to the local canines.)TCRH sits on the northern edge of town, and shortly beyond it the asphalt of Main Street gives way to dirt, the houses to open desert. It is the only hospital around for miles, and the highest-level trauma center (Level 3) on the entire reservation. A Level 3 designation, to review, stipulates that a general surgeon and anesthesiologist be "promptly available" for trauma activations, and in practice means that emergency physicians play a greater role in the initial resuscitation of these patients.1 While TCRH officially has 73 beds, including a small intensive care unit, staffing needs limit the actual inpatient census. A large proportion of sick patients (whether surgical or medical) have to be transferred to other hospitals by ambulance or helicopter.

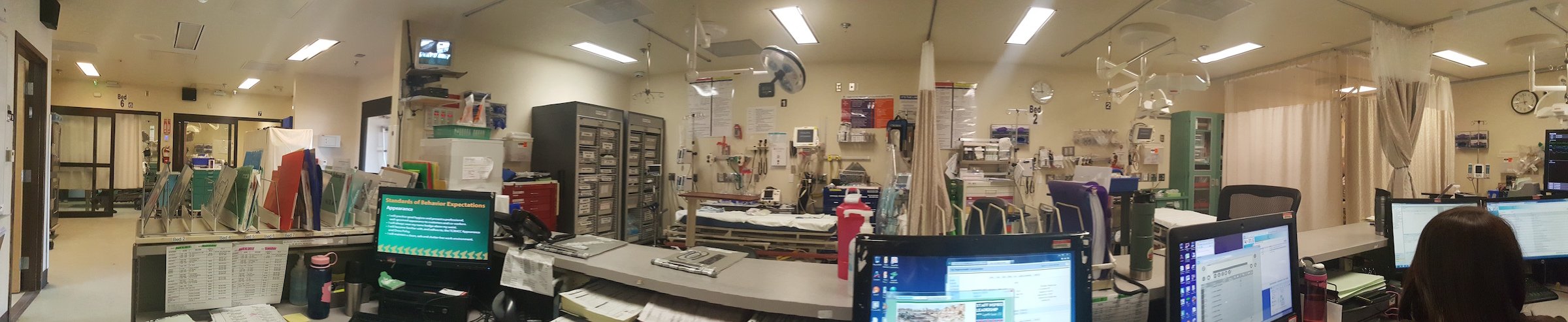

The TCRH Emergency Department accommodates 40,000 patient-visits per year - about 1/3 of them pediatric.

The TCRH Emergency Department accommodates 40,000 patient-visits per year - about 1/3 of them pediatric.The ED itself is a suite of 12 beds partitioned by curtains and has the feel of a converted auto body shop. Space is at a premium, and inadvertently "bumping into" colleagues often takes on literal meaning. This is especially true in the afternoon, when the floor space near the ambulance bay ("the Lounge") fills up with intoxicated patients. Ensconced in hospital chairs, they sleep, eat, or socialize until sober. Sounds and smells travel freely.

Still, together with the urgent care area across the hall ("the Annex"), the ED handles 40,000 patient-visits a year, about one-third of them pediatric. Making this number more impressive is the fact that work is done and information transferred through a hodgepodge of paper charts, computerized lab reports, and a separate PACS system. Here, patient stickers become an essential commodity and charts stack up precariously, every so often crashing to the floor with a jolting thud.4 Hands cramp from writing so much.

Besides the prevalence of alcohol-related disorders and diabetes, some unique epidemiologic features of the ED population that I witnessed were the presence of severe croup in kids (related to smoke from indoor fires) and interstitial lung disease in the elderly (from uranium mining), the need to consider hantavirus in patients with URI symptoms (Young person! Rat droppings! Thrombocytopenia!), and — refreshingly — the relative lack of opioid-seeking behavior.3–5

I worked twelve 12-hour shifts, and thanks to the rotation director had a lot of control over when I wanted to work. The ED staff is composed of EM-boarded/eligible younger attendings (more hands-on) and older attendings (more hands-off), some of whom are family physicians. Being able to see how a whole different set of emergency physicians, trained at different institutions, thought and practiced was one of the most valuable aspects of the rotation. For one of my shifts, I packed into a SUV with one of the public health nurses to do remote house calls, and gained a greater sense of the community TCRH serves.

This rotation afforded the opportunity to make house calls with public health nurses.

This rotation afforded the opportunity to make house calls with public health nurses.

There was plenty of downtime to explore, relax, or sleep. Housing was free and was shared with attendings from the ED group. Tuba City is an ideal jumping-off point to visit the Grand Canyon and other national parks, or to check out cities like Sonoma and Flagstaff. In sum, for any EM resident or medical student with an interest in remote EM, Native American health, and spending time in the great outdoors, consider an elective on the reservation in Tuba City.

References

1. http://www.amtrauma.org/?page=TraumaLevels.

2. Bernard K, Hasegawa K, Sullivan A, Camargo C. A Profile of Indian Health Service Emergency Departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(6):705-710.

3. Roscoe RJ, Deddens JA, Salvan A, Schnorr TM. Mortality among Navajo uranium miners. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(4):535–40.

4. Graziano KL, Tempest B. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: a zebra worth knowing. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(6):1015–20.

5. Simpson SQ, Spikes L, Patel S, Faruqi I. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24(1):159–73.