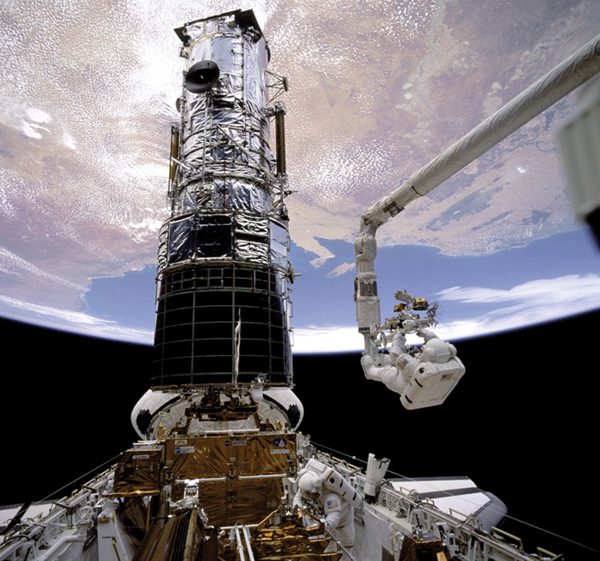

(All images courtesy of NASA. Above, emergency physician Scott Parazynski, MD, participates in an Extravehicular Activity during STS-120, the 23rd shuttle mission to the International Space Station.)

A physician is rarely included as part of a space flight crew. In the past 50 years of spaceflight, more than 400 people have flown in space, but only 26 have been American physicians. In 1973, Dr. Joseph Kerwin was the first U.S. physician selected for astronaut training, serving as the Science Pilot for the Skylab2 mission to the first U.S. orbital space station. Like Dr. Kerwin, when physicians have flown, they have served as scientists, engineers, spacewalkers, and project managers. Rarely has a physician-astronaut served as the on-board medical provider.

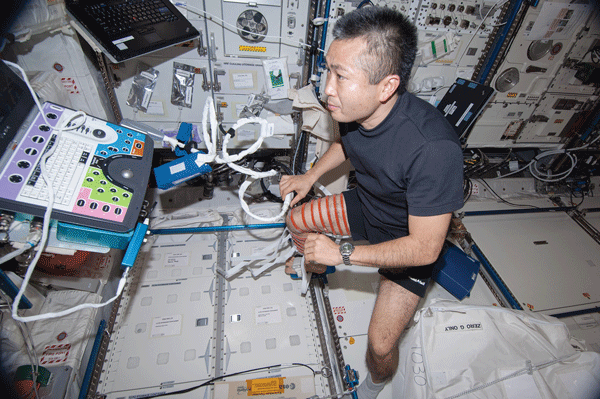

Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata performs an ultrasound scan using the Human Research Facility (HRF) Ultrasound2 on Expedition 38.

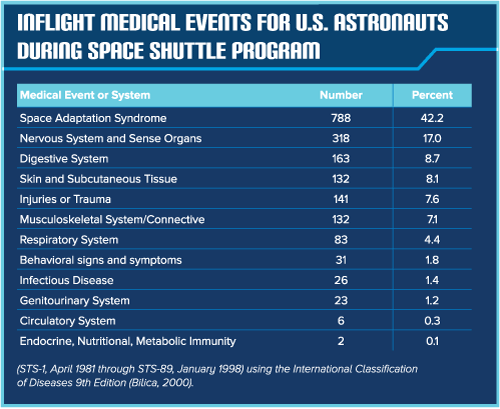

Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata performs an ultrasound scan using the Human Research Facility (HRF) Ultrasound2 on Expedition 38.Surprisingly, few serious medical emergencies in space have been reported. While documented conditions have included urosepsis, renal colic, cellulitis, pneumonitis, and cardiac arrhythmia, only 17 of these nonfatal severe medical events have been reported during spaceflight between 1961-1999.1 The relatively benign nature of medical problems in space flight is likely due to shorter missions, selection of healthy astronauts, on-board medications, and countermeasures to environmental effects and prolonged microgravity.2 The comprehensive profiling process includes an evaluation of astronauts' physiological and psychosocial well-being, medical history, and extensive laboratory and genetic markers. Astronauts also undergo simulations and classroom activities to prepare for these missions and the extraordinary events they may encounter.

When emergencies have occurred, they have been managed by both Earth-based medical teams and the assigned crew medical officer on board. The training of the crew medical officer includes limited medical instruction (less than 60 hours of training) and minor surgical skills such as suturing.2 That being said, medical kits on board include a large variety of supplies and medications, from stool softeners and Foley catheters to antipsychotics and tracheostomy tubes. Astronauts are additionally faced with the challenges of medical resuscitation in a microgravity environment, where usual physiologic conditions and advanced life support protocols may not even be relevant.

Thus, the medical training of physician-astronauts will become a valuable asset as plans for increased space travel and extended duration missions become reality. Furthermore, the physician with a background in emergency medicine seems ideally suited for such endeavors.

The Future

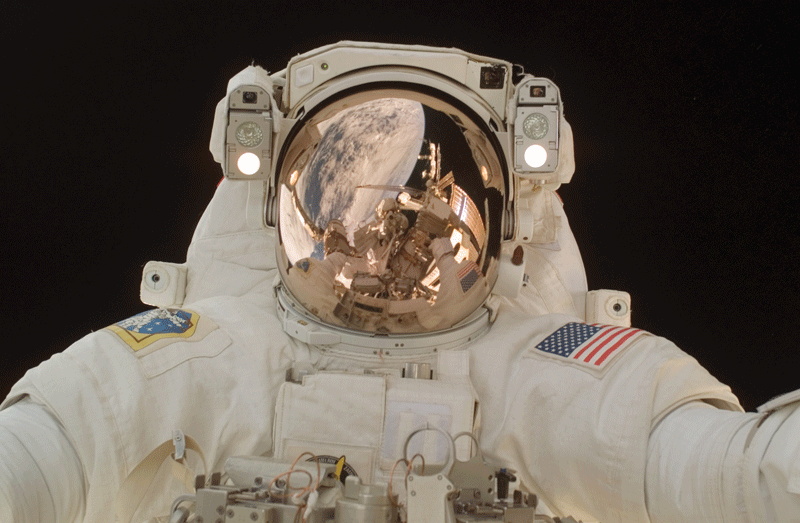

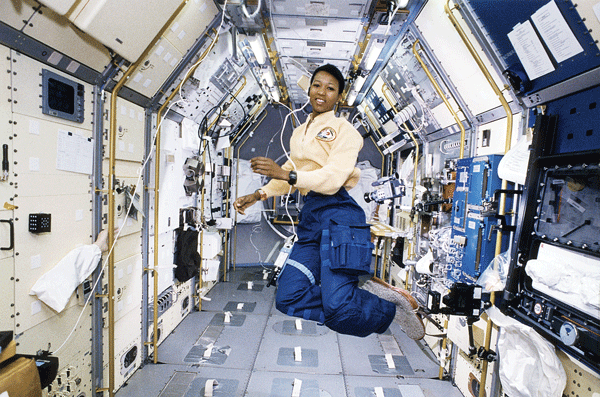

Mae Jemison, MD, (a general practitioner) floats in zero gravity at the Spacelab Japan Science module aboard STS-105, Endeavour.

Mae Jemison, MD, (a general practitioner) floats in zero gravity at the Spacelab Japan Science module aboard STS-105, Endeavour.With recent aerospace successes, such as the launch of the Orion spacecraft in December 2014, the Curiosity mission in Mars, and unmanned missions to comets and asteroids, the future of space flight seems promising. Plans for commercial space flight to the International Space Station (ISS), interplanetary expeditions, a return to the moon, colonization of neighboring planets, and establishment of bases are underway. Extended time in space inevitably leads to questions on how the Human Space Flight (HSF) program can support in-flight emergencies, particularly when a return to Earth may not be practical. For example, one study estimates that the risk of an emergency medical event during a 7-member space flight to Mars would be about 1 emergency event per trip. This may seem negligible until put in the context of a 6-month return to Earth.1,3 Thus, the capability to administer advanced care for illness and injury will undoubtedly be a prerequisite for interplanetary travel and prolonged human spaceflight beyond low Earth orbit.2 Additionally, as space vehicles move further from Earth's orbit, telemetric medical support and traditional communication traveling at the speed of light will have a longer delay (eg, in the case of Mars, two-way radio contact will require a minimum of 44 minutes).2 Given such delays, the current practice of relying on Earth-based medical consultation and a crew medical officer without extensive medical training may no longer be enough.

The preparation for medical emergencies in future missions will require using experience from previous missions, submarines expeditions, remote habitats, stations in extreme environments like Antarctica, and simulations. Other medical events unique to space also must be anticipated, particularly higher incidence of space radiation, injuries from increased extravehicular activities, space debris, and increased susceptibility for infection.

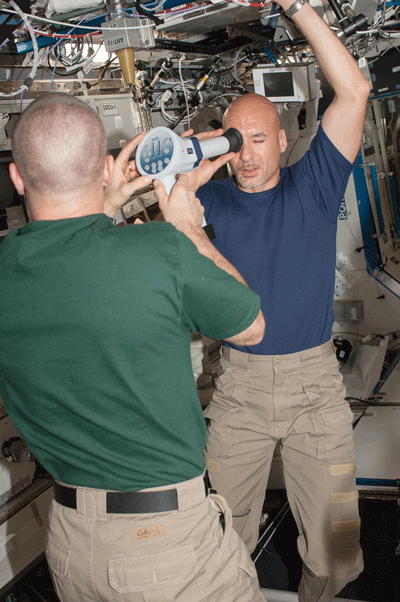

Astronaut Luca Parmitano collects fundoscopic images with the help of astronaut Chris Cassidy for the Ocular Health experiment.

Astronaut Luca Parmitano collects fundoscopic images with the help of astronaut Chris Cassidy for the Ocular Health experiment.Future space travelers are unlikely to be as fit and healthy as past astronauts, adding to the likelihood of increased medical incidents in space. As NASA redirects its scope beyond low Earth orbit, the goal of commercial space travel is being pursued by private agencies. Despite the fatal October 2014 crash of Virgin Galactic SpaceShipTwo, Virgin continues with the development of a vehicle for customers wishing to undertake suborbital travel. The ISS medical community has issued standards for spaceflight participants (“space tourists”) to the station. The Federal Aviation Administration has also issued regulations on operating space taxis, including general security, training, and minimum health restrictions for potential customers. Despite these restrictions, the space tourist will be less healthy and less equipped to handle emergencies than previous space travelers who spent years preparing for a mission.

Although a Soyuz spacecraft docked on the ISS can be used for evacuation today, space emergency medical systems and emergency departments may soon adopt more visible roles as more tourists fly and as extended missions become a reality. International space agencies will need to provide advanced medical care for acute illness and injury and manage the safe return of astronauts.

Emergency Physician-Astronauts

Only 5 EM-trained American physician-astronauts have flown in space: Thomas Marshburn, MD; Anna Fisher, MD; William Hendrick Fisher, MD; Scott Parazynski, MD; and Kjell Lindgren, MD.4 The emergency medicine training experience has many qualities that make emergency physicians the best potential medical providers for the future of human space flight: comfort with rapid assessment and treatment, resuscitation expertise, ability to perform a wide range of advanced procedures, exposure to diverse pathologies, and creativity in resource limited settings. Given that the models for extended missions are based in part on experience from extreme environments and remote settings, training in wilderness medicine will also complement the skillset necessary for future space endeavors.

In addition, all emergency medicine graduates must demonstrate competency in bedside ultrasound, also the main imaging modality in space because of its portability and the fact that images are not affected by space radiation. In fact, the ultrasound in ISS has proven useful in evaluating the musculoskeletal system, performing FAST exams, renal and bladder surveys, ocular exams, and even nitrogen bubbles in the presence of decompression sickness.5

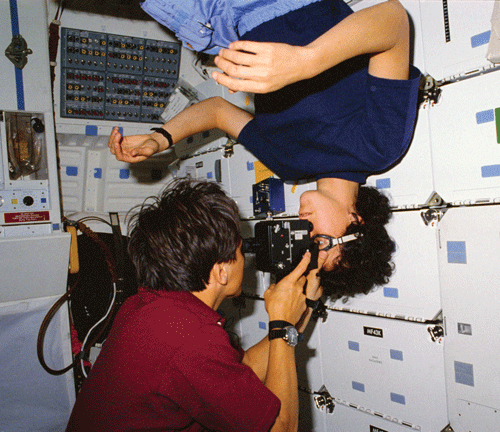

Astronaut Franklin R. Chang-Diaz performs an eye exam on astronaut Ellen S. Baker, MD, MPH, on the middeck of the Earth-orbiting space shuttle Atlantis.

Astronaut Franklin R. Chang-Diaz performs an eye exam on astronaut Ellen S. Baker, MD, MPH, on the middeck of the Earth-orbiting space shuttle Atlantis.The HSF program will be faced with many challenges in clinical management as space exploration progresses to longer missions, interplanetary travel, and extraterrestrial colonization. It is now suggested that a physician be included in every spaceflight crew on long-duration space flights in order to enhance mission safety.6 Physician-astronauts will be a valuable asset to these missions because of their adaptability to be scientists, engineers, managers, and clinicians who can manage space emergencies and provide long-term crew health monitoring. Because of the training and experience, emergency physicians seem the ideal clinical specialists for providing these medical services.

Canadian physician-astronaut Robert Thirsk, MD, wrote an editorial on similarities in the training experience of physicians and astronauts. “The knowledge, skills, and attitudes of a clinician are valuable but not sufficient, of course, to be an astronaut,” he wrote. “A burning passion for space exploration is also required. We take our inspiration from John F. Kennedy, who, when the United States was initiating its Apollo moon program, declared, ”˜We choose to go to the moon, not because it is easy, but because it is hard'... For some people, the benefits of space exploration do not outweigh the arduous work and risk. For physician-astronauts, they clearly do.”7

References

- Summers RL, et al. Emergencies in Space. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;46:177-184.

- Stewart LH, Trunkey D, Rebagliati GS. Emergency Medicine in Space. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(1):45-54.

- Kuypers M. “Emergency and Wilderness Medicine Training for Physician Astronauts on Exploration Class Missions.” Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2013;24(4):445-449.

- NASA astronaut biographies. www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/. Accessed Dec. 30, 2014.

- Law J, Macbeth PB. Ultrasound: From Earth to Space. McGill J Med. 2011;13(2): 59-58.

- Bridge LM, Watkins S. Impact of Medical Training Level on Medical Autonomy for Long-Duration Space Flight. NASA/TP-2011-216159. January 2012.

- Thirsk R. Physicians as Astronauts. McGill J Med. 2011;13(2):69.