Based on recent ERAS data, medical student applications to EM residencies are significantly decreasing for the second year in a row.

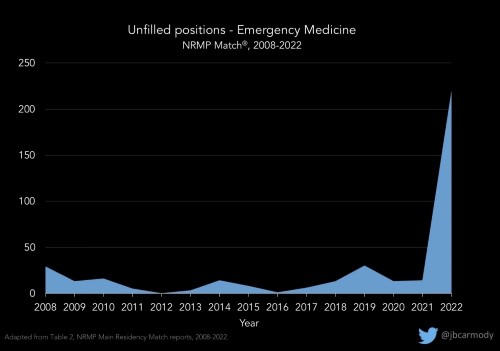

In Match 2022, many programs had unfilled positions that were later filled with unmatched medical student applicants from the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP) at higher rates than had been seen in years. This spring, that trend is expected to be even more prevalent.

To quote Match expert Dr. Bryan Carmody, “The decline in applicants isn’t a problem per se – it’s a sign of bigger concerns. It’s like fever, or metabolic acidosis, or sinus tachycardia. It’s just an outward manifestation of internal problems, and it’s best managed not by treating it directly, but by addressing the underlying cause.”

I agree. This is likely a ripple effect of underlying issues mounting in emergency medicine. And if programs hope to recover their formerly competitive medical student recruiting, and applicants hope to match without the stressful scramble of the SOAP, we will all have to reckon with several structural and cultural challenges in EM that have come to a head in recent years.

But first, it’s essential that residents, program directors, and medical students understand this data and the factors at play in these trends. We must listen to the concerns that medical students cite when discussing their hesitancy to join EM. And we must share ways you can join EMRA in innovating solutions to these issues and recruiting EM’s next generation of clinicians, educators, and leaders.

The Data

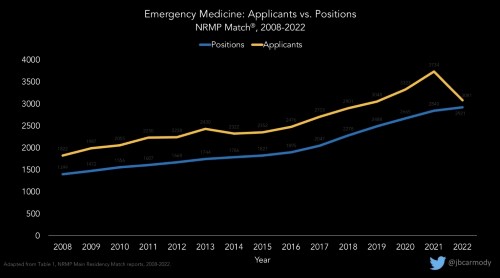

For years, applicants to EM increased in parallel with the increase in residency positions. Consistently, there were a greater number of applicants than residency positions, and the number of EM residency positions left unfilled through the Match was fewer than 30 for more than 15 years. This made even those unfilled positions highly competitive when they became available through the SOAP.

In the past 3 years, the number of applications has taken a downturn, decreasing by 20% since 2020. Applications received per program have decreased even more, down 30% since 2020. In the 2022 Match, this decrease resulted in 219 unfilled positions. Almost all were filled through the SOAP. Given these trends, the number of unfilled positions through Match 2023 may be even greater.

Graph courtesy of Dr. Bryan Carmody, used with permission.

Graph courtesy of Dr. Bryan Carmody, used with permission.

This data, while preliminary, is a useful predictor for Match 2023. It comes from ERAS statistics obtained Oct. 5, 2022. At this point in the 2023 Match cycle, ERAS has most likely received the majority of MD and DO applicants anticipated, and MD applicants have demonstrated the most profound decrease at 31%. IMGs have actually increased in the same timeframe by 28%, though these applicants are more likely to go unmatched than their U.S. counterparts.

This decrease in applicants is exacerbated at the program level by increases in programs’ class sizes and openings of new programs. Between 2018 and 2022, 643 new positions were added to the EM Match, an increase of 28.2%.

Notably, after the SOAP almost every EM position does fill, with hundreds of applicants to EM remaining unmatched even after the SOAP in 2022 (though it’s unknown how many of these applicants may have dual-applied and ultimately matched into another specialty). In contrast, some other specialties routinely have positions remaining empty, even after SOAP.

Medical Student Hesitancy

EMRA members span all stages of EM careers, including more than 3,500 medical student members with a passion for our specialty. Some have shared with EMRA the concerns that have made them more hesitant about a career in EM, and that have made their classmates choose other specialties entirely.

Some are concerned about the future of the EM job market, which felt more bleak in the wake of the 2021 workforce report The Emergency Medicine Physician Workforce: Projections for 2030. The report predicted a surplus of 7,845 EM physicians by 2030. For medical students saddled with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt or for those with geographic ties or career considerations limiting where they would want to work, the concern about saturated job markets was enough to drive them away. Some medical students have cited specifically the corporate practice of medicine encroaching on hiring, firing, and staffing decisions, and on the increased independent practice of NPs and PAs as factors making EM less attractive.

Compounding the impact of the workforce report, it was released at a time when ED visits hit a nadir not seen in recent years, resulting in reduced staffing, and during an unusually difficult job market for the graduating resident class of 2021. Even at the time, this challenge was expected to be a short battle, and we have since recovered with many EDs reporting volumes surging past pre-COVID-19 levels. However, with this unfortunate timing, the unfavorable 2030 job market seemed even more imminent than projected.

Some EM-bound medical students express that there are causes beyond the job market that need to be addressed. In fact, some say the workforce report is almost used as a scapegoat to avoid reckoning with other changes to emergency medicine that have afflicted the specialty.

For example, since the COVID-19 pandemic, the topic of physician burnout and suicide has been dominating headlines more than ever. EM nurses and physicians in particular have been bold advocates for transparency in our personal struggles with the tragedies and violence we experienced through the pandemic. This has resulted in great strides in breaking down the stigma associated with mental health, and even led to federal legislation with the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act. This also has resulted in greater attention to ensuring our EDs take measures to protect us with adequate PPE, security in seeking psychiatric help, and procedures for responding to workplace violence.

At the same time these stories were impressing upon administrators and legislators the importance of systemic change in healthcare, these stories were also reaching medical students and painting a stress-inducing portrait of daily life in the ED. And in the setting of our legitimate concerns about our wellness and personal safety amid the pandemic, it was difficult to tactfully share the rewarding aspects of our work as well. Some emergency physicians have attempted, via social media, to offer hope that the future of EM is bright and have shared that they still enjoy their daily work, only to be labeled toxic-positivity-spewing physicians with their heads in the sand. Communicating the complexity of the frustrations, triumphs, honor, and pain that comes with this work is difficult to achieve in just 280 characters.

And offline, these students, more than classes before them, did not have the counterbalance of clinical experiences in the ED to show them the rewarding aspects of our work saving lives and supporting the underserved. Rather, our medical student members reported that their clerkship experiences were limited: Some were told not to see any patients with respiratory or infectious complaints due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and some didn’t have the ability to complete a third-year EM clerkship at all. Many had completely inactive emergency medicine interest groups through the first years of medical school when they would have otherwise been in simulation workshops learning to suture, intubate, and resuscitate critically ill patients.

The Effects: Impending Doom or Blue Skies

In speculating on the downstream effects of this change in the competitiveness for an EM residency placement, it is easy to speak in extremes. However, a nuanced discussion carried out with compassion for the applicants who are still applying to EM may be more productive.

On one hand, we should not ignore recent trends and statistics. We should take the cue that this specialty may not be as attractive as it once was, and be self-critical enough to address the elements at play that do actually warrant intervention. To take a more positive perspective, however, EM will not suddenly wither away now that we have slightly fewer unmatched applicants, stressed about their inability to join their chosen specialty. Furthermore, EM has not been made better by having hundreds of unmatched applicants, redirected through family medicine training for example, who go on to staff EDs without being residency-trained in EM.

It’s also essential to note that half of medical students are below average, but, thanks to our educators, educational resources, and the accreditation processes in place for medical schools and residencies, the majority of them go on to become excellent physicians who do what is best for their patients. Likewise, EM residents who join their programs through the SOAP can become excellent physicians and make a lasting impact on their programs. EMRA is as proud to represent these resident members as we are of the ones who matched at the top of their rank list.

However, the process of obtaining a placement through the SOAP is extremely stressful for the applicant as well. Immediately after finding out they’re unmatched, they must reach out to programs and commit themselves and their families to living 3 to 4 years in a city they may have never seen and train in a program they know very little about. Addressing these trends and decreasing the number of residents matching through the SOAP is not intended to disparage these applicants. It is intended to benefit those who would be sent through the SOAP.

Solutions: Supporting Students

We must accept that, ultimately, students choose the specialty they feel is their best fit. But if we want to ensure that students give EM a fair chance, we need to recruit consistently across medical schools and from pre-med shadowers to the residency interview trail.

Investing time and support in shadowing and EMIG activities is foundational to effective recruiting and should be standard across schools. Residents should be mentoring EM-interested students where possible, locally or through EMRA’s Student-Resident Mentorship Program.

Third-year EM clerkships must be available and accessible. For students without a home EM rotation, particularly DO students, we recommend the CORD guide designed to direct them through the rotation and application process.

In their clerkships, we must ensure that students feel they are part of the workflow and are valued in the emergency department. They should actually be talking to patients and participating in procedures, not treated as an inconvenience or a scribe.

Throughout their acting internships, they’ll be less likely to be relegated to the SOAP if they get excellent direct feedback and have a chance to reach their greatest potential before their SLOEs are submitted.

Solutions: At the Program Level

When it comes to the application and interviewing process, programs that are routinely unfilled by the Match must adapt quickly. Programs with difficulty matching must accept that they are competing with a larger-than-ever number of programs for a small subset of applicants. It may be time to re-evaluate their ERAS filters and interview more DO and IMG applicants.

On the EMRA side, we are working to share the perspectives of DO and IMG residents who have secured EM residency positions in order to share their advice with upcoming applicants to EM, and we would encourage our members to review CORD’s guides such as their IMG Applying Guide.

Solutions: The Future of our Specialty

We need to ensure that students, our colleagues, and our patients understand that, though we are concerned about these challenges, we are led by EM residents, mentors, and partners tackling these issues head-on. We are focused on innovative solutions that address specific barriers to providing efficient, effective care.

In the wake of the workforce study, we want your transition from medical school to residency, and residency to the job market, to be as smooth as possible. That’s why we’ve launched EMbark, your career-planning center, where you’ll find resources and information dedicated to helping you plan your professional path as you progress through medical school and residency.

The unfavorable workforce projections are attributed to several trends in the world of EM employment, such as corporate entities’ influence on hiring, firing, and the practice of medicine; PA and NP independent practice; and the expansion of residency positions, among others. To educate residents on these issues, we provide the Emergency Medicine Advocacy Handbook for free online. To take an active role in educating your fellow residents on these topics and guiding EMRA’s response to these conflicts, join the Health Policy Committee or Administration and Operations Committee.

Leaders in EM are also examining the practices of specialties that have become more attractive during the same time period. Since 2020, applicants to anesthesia have increased by about 20%. It’s an important comparison, because anesthesia has rebounded well from concerns that it too had an oversaturated job market with competition from CRNAs. Anesthesia adapted by expanding into pain clinics, becoming interventionists, and taking on a supervisory role for OR anesthesia. This innovation is part of what has made anesthesia an extremely attractive specialty again. This could be analogous to the many ways EM is responsibly expanding its scope, such as through telemedicine, sports medicine, urgent care centers, rapid diagnostic centers, and more.

ED boarding has also been increasingly challenging, causing worse outcomes for both patients and residents. EMRA signed a letter penned by ACEP leadership calling for the White House to convene a summit of leaders in health services to address this complex issue and identify solutions across our healthcare system.

In the meantime, boarding poses a threat to EM residents’ education. This crisis is especially concerning for EM residents who must continue to manage boarding patients even after they are admitted. This is an area where EMRA leaders can advocate at the program level to ensure EM residents remain focused on the undifferentiated patients who need an EP and are not yet admitted. The gridlock has kept our hospitals on diversion for weeks or months at a time, limiting our exposure to critically ill transfer patients who need advanced treatment at our academic centers. Now is the time for us to share these concerns.

To address burnout, EMRA believes first in mitigating unnecessary stressors that push us to unhealthy levels of stress. EMRA leaders serve as our bridge to the ACGME, the AMA, CORD leadership, and other program leaders to advocate for fair working conditions, adequate leave, and security in seeking mental health support.

The expansion of residency programs is a unique challenge, especially in regions where more residents are graduating than local job markets can accommodate. For now, it’s up to program leadership to determine whether they are expanding their residency programs for educational and training purposes, or whether these spots are being used simply as a profitable workforce for the emergency department. The role of regulatory bodies like the ACGME is limited, in that they are intended to control the quality of our training, and not the availability of jobs.

When we address these issues with solutions instead of cynicism and divisiveness, I think it’s easier for our frustrations and gratitude to coexist. Through every storm our specialty has weathered in the last half a century, that gratitude has remained. We should always be able to acknowledge the honor it is to serve patients who have no one else to care for them. To bring people back from the brink of death. To sit with people on the worst days of their lives. To be part of awesome teams, and to have space in our lives for family, diverse career interests, and so much more. It’s up to us to protect that legacy.