Primary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage (PTH) is a potentially life-threatening complication with high mortality rates. The lack of clear stepwise guidelines for its management poses a challenge for health-care providers.

We discuss 2 cases of patients who presented with severe primary PTH. Our cases highlight the successful use of alternative treatment options. Due to limited access to specialized care and a compromised airway, we employed an alternative approach by administering intravenous (IV) tranexamic acid (TXA) to control bleeding. The successful use of IV TXA, along with surgical intervention for bleeding, resulted in the cessation of the hemorrhage.

These cases highlight the potential role of IV TXA as an effective treatment option in patients with PTH and high risk for compromised airways, emphasizing the need for further investigation and consideration of alternative strategies in the absence of clear guidelines.

Introduction

PTH refers to the occurrence of bleeding within 24 hours of tonsillectomy, typically involving active bleeding, hypotension, and tachycardia. This complication is well-recognized in previous studies1 and occurs in 0.2% to 2.2% of patients undergoing tonsillectomy; current U.S.-reported mortality rates for tonsillectomy are 1 per 2,360 and 1 per 18,000 in inpatient and ambulatory settings, respectively. One-third of deaths are attributable to bleeding. The association between different surgical techniques and rates of primary post-tonsillectomy bleeding remains unclear due to conflicting evidence.2 Additionally, research has shown that post-operative instructions given to patients concerning diet and physical activity vary greatly.3

In emergency settings, health-care providers face significant challenges in managing PTH due to the absence of well-defined stepwise guidelines and limited availability of ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialists to deliver specialized care. Currently, the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery does not provide specific guidelines for managing PTH.1

Research shows that various management strategies are employed in the pediatric population to address post-tonsillectomy bleeding.4 These include administration of intravenous (IV) fluids, direct pressure application, clot suctioning, silver nitrate use, placement of vasoconstrictor-soaked pledgets, epinephrine injections, topical epinephrine application, utilization of thrombin powder, and laboratory investigations. However, an optimal management approach lacks consensus.

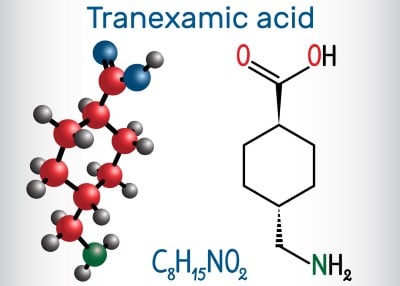

Recent studies demonstrate the use of nebulized tranexamic acid (TXA) as a potential treatment option for acute bleeding as a result of PTH. TXA is an antifibrinolytic agent that inhibits the breakdown of blood clots. A study by Schwarz et al. (2019) reported the successful use of nebulized TXA in managing pediatric secondary PTH.5 Additionally, nebulized TXA offers a non-invasive method of administration and has shown promising results in controlling bleeding prior to definitive surgical intervention.6

In this case series, we discuss the management of 2 patients who experienced PTH, emphasizing the successful use of IV TXA in the presence of a compromised airway and limited access to specialized care. This alternative approach highlights the potential role of IV TXA as an effective treatment option in patients with PTH and compromised airways. These cases underscore the need for further research and the development of evidence-based guidelines to optimize the management of this potentially life-threatening complication.

Case Descriptions

Case 1

A 16-year-old female patient with a history of tonsillitis underwent an uneventful tonsillectomy. On the first postoperative day, the patient presented to the ED with a 30-minute history of hemoptysis, expectorating blood into a receptacle, and reported significant blood loss since onset. This was verified through an examination of the receptacle containing an estimated volume of 2 liters of blood, corroborating the reported extent of hemorrhage.

The patient exhibited pallor and concerns for a compromised airway due to copious volumes of blood within the oropharynx, accompanied by persistent hemoptysis, necessitating urgent intervention to maintain airway patency. She was anxious-appearing and tachycardic with a heart rate of 173. The patient’s oral cavity exhibited a substantial accumulation of clotted blood, resulting in a complicated visualization of the posterior oropharynx and impeding further identification of the bleeding source. Despite the patient’s ongoing expectoration of substantial volumes of blood from the oral cavity, she maintained adequate oxygen saturation and clear breath sounds, effectively averting aspiration concerns for the time being. Given that the patient was currently protecting her airway, the decision was made to trial medical management with a low threshold for intubation if needed.

Immediate intervention was initiated, including seating the patient upright and suctioning the airway. Two large-bore IV lines were established, and massive transfusion protocol (MTP) was initiated. Nebulized TXA was attempted initially. However, it was complicated by the patient’s repeated efforts to maintain a patent airway as well as bleeding, which could limit the nebulized effects of TXA. During attempts to administer blow-by nebulized TXA to the patient via a mask, she consistently expectorated significant quantities of blood, rendering the treatment administration ineffective. IV TXA was then administered in an attempt to control the significant amount of bleeding.

While resuscitative efforts were ongoing, a consultation was sought from the patient’s otolaryngology (ENT) surgeon but was unsuccessful due to lack of hospital privileges. Therefore, the on-site trauma surgery team was engaged for surgical management. Additionally, anesthesia consultation was obtained for assistance in airway management.

As bleeding began to slow, the interdisciplinary team engaged in discussions regarding airway management, particularly the option of endotracheal intubation. After careful consideration of the patient’s ability to protect her own airway, endotracheal intubation in the ED was postponed. This was due to the potential risk of compromising muscle tone in the oropharynx, which could exacerbate the bleeding. Additional concerns arose regarding the patient’s ability to effectively clear her airway once sedated. Meanwhile, the patient was managed in an upright position, and the airway was suctioned in preparation for transferring her to the operating room.

She was promptly taken to the operating room for surgical intervention. Upon the patient’s arrival in the operating room, hemorrhage had ceased, enabling the surgical team to proceed safely with sedation and endotracheal intubation without encountering any subsequent complications. Intraoperative findings revealed a clotted arterial bleed from the right tonsillar fossa, which was successfully cauterized. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged 2 days later in stable condition.

Case 2

A 26-year-old female patient who underwent a routine tonsillectomy procedure presented to the ED 1 day after the surgery with a distressing episode of bright red, bloody emesis, accompanied by the expulsion of clots. Notably, the emesis bag contained approximately 1 liter of blood. On examination, the patient appeared anxious and was found to be tachycardic, with a heart rate of 100 beats per minute, while all other vital signs remained within normal ranges. Physical examination revealed bright red blood oozing from the right tonsillar fossa, consistent with active bleeding, alongside bright red emesis and clots. Despite the alarming presentation, the patient maintained a patent airway, and her oxygen saturation level was stable at 100%.

Immediate intervention was initiated to manage the hemorrhage. As a first-line measure, an attempt was made to administer nebulized TXA to control the bleeding. However, the patient did not show significant improvement with this treatment approach. Given the urgency of the situation, ENT specialists were promptly consulted for further management guidance.

The ENT team recommended the IV administration of TXA to address the ongoing hemorrhage. Following the IV TXA administration, there was notable improvement in the oozing from the hemorrhage site, indicating a positive response to the intervention. Continuous monitoring and reassessment demonstrated a resolution of the oozing bleeding, providing initial relief and stability for the patient.

However, despite initial improvement, the patient experienced another concerning episode of bright red, large-volume emesis during subsequent evaluation. Reassessment of the right tonsillar fossa revealed ongoing oozing of blood, though to a lesser degree than before, suggesting that the bleeding had been slowed but not fully controlled.

Once again, ENT specialists were consulted, and in light of the persistent hemorrhage and potential complications, they recommended the transfer of the patient to a hospital equipped with specialized ENT coverage. Following the ENT team’s advice, arrangements were made to facilitate the patient’s transfer to a suitable facility for further evaluation and targeted management.

Discussion

PTH is a critical complication that can result in life-threatening situations, necessitating prompt and appropriate management. However, the absence of well-defined stepwise guidelines for PTH treatment poses significant challenges for health-care providers, particularly in emergency settings.

The patients in our 2 cases experienced substantial and potentially fatal hemorrhages, posing high risks for compromised airways requiring immediate intervention. In these cases, the successful use of IV TXA highlights its potential role in controlling bleeding in PTH. Nebulized TXA was initially attempted, but IV administration was necessary due to risk for airway compromise. The administration of TXA resulted in decreased blood loss and cessation of hemorrhage.

The effectiveness of TXA in stopping bleeding in patients with traumatic bleeding is evident in the CRASH-2 trial.7 The study demonstrated a clinically significant reduction in all-cause mortality, including complications of vascular occlusive events, at 28 days with TXA compared to a placebo. Furthermore, the risk of death, specifically due to bleeding, was significantly reduced in the TXA group (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.76 to 0.96; p = 0.0077). Importantly, the effect of TXA on death due to bleeding varied based on the time from injury to treatment, with early administration (≤ 1 hour from injury) showing a significant reduction in the risk of death due to bleeding (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.82; p < 0.0001).

These findings provide strong evidence for the efficacy of TXA in reducing mortality due to bleeding, particularly when administered early after injury, and address the concern for vascular occlusive events, which were included in the study as a primary outcome event and demonstrated a decrease in all-cause mortality.

The administration of TXA in pediatric trauma patients has been a subject of interest due to its potential to reduce bleeding and improve outcomes. A study by Eckert et al. (2014) specifically evaluated the use of TXA in a combat setting and its impact on pediatric trauma patients.8 Patients who received TXA had greater injury severity, hypotension, acidosis, and coagulopathy than those in the no-TXA group. Findings indicated that TXA administration was associated with decreased mortality rates in this population. Moreover, the study provided evidence of the safety profile of TXA in pediatric patients. The authors reported no significant adverse complications related to TXA administration in their cohort. This supports the notion that TXA can be utilized safely in pediatric patients without posing significant risks of clotting.

In addition to the aforementioned study of pediatric trauma patients, substantial research supports the use of TXA in various surgical procedures involving pediatric patients. Urban et al. conducted multiple studies exploring the benefits of TXA in major spine, cardiac, and craniofacial surgeries.9 The findings from these studies and meta-analyses examining TXA use in pediatric surgery consistently demonstrate favorable outcomes associated with TXA administration.

The safety of TXA use in bleeding patients has been studied by Myles et al in more than 4,000 patients undergoing cardiac surgery with primary outcomes of death and thrombotic events.10 The results showed that TXA administration was associated with a lower risk of bleeding compared to the placebo group, without an increased risk of death or thrombotic complications within 30 days after surgery. A primary outcome event occurred in 386 patients (16.7%) in the TXA group and in 420 patients (18.1%) in the placebo group (relative risk, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.81 to 1.05; P=0.22). The total number of units of blood products that were transfused during hospitalization was 4,331 in the TXA group and 7,994 in the placebo group (P<0.001). Major hemorrhage or cardiac tamponade leading to reoperation occurred in 1.4% of patients in the TXA group and 2.8% of patients in the placebo group (P=0.001), and seizures occurred in 0.7% and 0.1%, respectively (P=0.002 by Fisher’s exact test).10 These findings suggest that TXA effectively reduced bleeding without compromising patient safety in the short term. However, it was noted that there was a higher risk of postoperative seizures in patients receiving TXA. Despite this observed risk, the overall safety profile of TXA remains favorable, and its benefits in reducing bleeding complications are apparent.

Most recently, research published in the American Journal of Otolaryngology evaluated the safety and efficacy of TXA in PTH. The study involved a retrospective chart review of 1,428 adult and pediatric patients who underwent tonsillectomy at a tertiary care hospital with continuous otolaryngologic coverage over a 2-year period.11 According to the study, 27 out of 55 PTH patients received topical, nebulized, or IV TXA. No adverse effects were noted with TXA administration. The usage of TXA in treating PTH demonstrated a resolution of hemorrhage in 77.8% of patients. Additionally, the study observed a reduction in the need for operating room cauterization in those patients treated with TXA compared to those who did not receive TXA. These findings support the safety and effectiveness of TXA administration, regardless of the mode of delivery (IV, nebulized, or topical applications), in pediatric and adult populations with PTH.

In cases of primary PTH where attempts at surgical control are ineffective, research has shown that the use of endovascular embolization has been considered as an alternative intervention.12 Endovascular embolization involves the selective occlusion of bleeding vessels using embolic agents, thereby promoting hemostasis. However, in the presented cases, the timely and effective administration of IV TXA played a crucial role in avoiding the need for endovascular embolization. The administration of IV TXA, along with surgical cauterization of the arterial bleed, successfully halted bleeding and achieved control of the hemorrhage. The findings from these cases align with the trends reported in the literature, highlighting the importance of exploring non-invasive approaches such as IV TXA before resorting to more invasive measures like endovascular embolization.

Based on our findings, TXA appears to be a safe and effective treatment option for managing post-tonsillectomy bleeding in both pediatric and adult populations. However, further research, including prospective studies and randomized controlled trials, would be beneficial to establish standardized guidelines and optimize the use of TXA in PTH.

Conclusion

The presented cases of severe PTH highlight the potential role of IV TXA as an effective treatment option in acutely bleeding patients, particularly in cases with high risk for airway compromise. In our cases, the successful administration of IV TXA, along with surgical intervention for arterial bleeding, resulted in effective control and resolution of the hemorrhage.

The efficacy of TXA in managing bleeding in various clinical scenarios, including trauma and major surgeries, is supported by a body of research. Studies have demonstrated that TXA administration leads to decreased blood loss and a reduced need for blood product transfusion, contributing to improved patient outcomes. Furthermore, recent research specific to PTH has shown promising results regarding the safety and effectiveness of TXA in resolving hemorrhage, with a reduction in the need for additional invasive interventions.

While the presented cases and existing research highlight the potential benefits of IV TXA in managing severe PTH, further investigation is still needed. Prospective studies and randomized controlled trials are necessary to establish standardized guidelines for using TXA in this specific context. These guidelines would help health-care providers in emergency settings to navigate the challenges posed by severe PTH and ensure appropriate and timely interventions.

The lack of clear stepwise guidelines for managing severe post-tonsillectomy bleeding emphasizes the importance of ongoing research and the development of standardized protocols. With standardized guidelines, health-care providers would have a clear framework for prompt and appropriate management, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing morbidity and mortality associated with this potentially life-threatening complication.

References

- Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, et al. Clinical Practice guideline: Tonsillectomy in children (Update). Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2019;160(1_suppl):S1-S42. doi:10.1177/0194599818801757

- Pynnonen MA, Brinkmeier JV, Thorne MC, Chong LY, Burton MJ. Coblation versus other surgical techniques for tonsillectomy. The Cochrane Library. 2017;2017(8). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004619.pub3

- Cohen DJ, Dor M. Morbidity and mortality of post-tonsillectomy bleeding: analysis of cases. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2007;122(1):88-92. doi:10.1017/s0022215107006895

- Clark C, Schubart JR, Carr MM. Trends in the management of secondary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2018;108:196-201. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.03.004

- Schwarz W, Ruttan T, Bundick K. Nebulized tranexamic acid use for pediatric Secondary Post-Tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2019;73(3):269-271. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.429

- Dermendjieva M, Gopalsami A, Glennon N, Torbati SS. Nebulized tranexamic acid in Secondary Post-Tonsillectomy Hemorrhage: Case Series and Review of the literature. Clinical Practice and Cases in Emergency Medicine. 2021;5(3):289-295. doi:10.5811/cpcem.2021.5.52549

- Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats TJ, et al. The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health Technology Assessment. 2013;17(10). doi:10.3310/hta17100

- Eckert MJ, Wertin TM, Tyner SD, Nelson DW, Izenberg S, Martin MJ. Tranexamic acid administration to pediatric trauma patients in a combat setting. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2014;77(6):852-858. doi:10.1097/ta.0000000000000443

- Urban D, Dehaeck R, Lorenzetti D, et al. Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid in bleeding paediatric trauma patients: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012947. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012947

- Myles PS, Smith JA, Forbes A, et al. Tranexamic acid in patients undergoing Coronary-Artery surgery. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(2):136-148. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1606424

- Spencer R, Newby M, Hickman WP, Williams N, Kellermeyer B. Efficacy of tranexamic acid (TXA) for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 2022;43(5):103582. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103582

- Windsor AM, Soldatova L, Elden L. Endovascular embolization for control of Post-Tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Cureus. February 2021. doi:10.7759/cureus.13217