Case Introduction

A 39-year-old male presented to the emergency department with urinary retention and scrotal swelling. He had undergone an external hemorrhoidectomy 3 days prior to presenting, but had an otherwise unremarkable medical history.

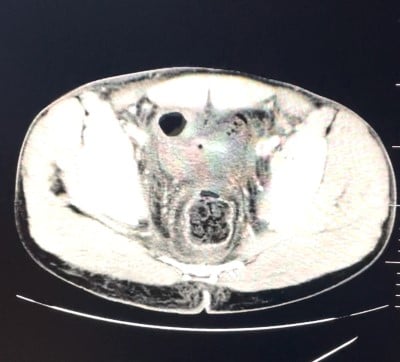

He had been evaluated by an outpatient urologist, who placed a foley catheter and referred the patient for a CT scan. The CT scan showed fluid-tracking involving the paracolic gutters, pelvic fat stranding, diffuse mucosal thickening of distal rectum and anus, diffuse subcutaneous edema of gluteal regions, and soft tissue swelling involving the scrotum; there was no evidence of subcutaneous emphysema (Figures 1 and 2). Upon receiving the CT results, the urologist immediately referred the patient to the ED. Differential diagnoses considered included gas gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis, and pelvic infection.

Upon initial evaluation in the ED, the patient was alert and oriented and complained only of nausea. Initial vital signs were within normal limits. The patient denied pain in the genital area. He was taking ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and oxycodone routinely after surgery. On exam, the perineal area was pink and well-perfused with induration but no crepitus. The scrotum was significantly edematous with phimosis. Intravenous fluids, labs, and broad spectrum antibiotics were ordered. Point-of-care lab results were pH 7.19 and lactate of 9.1. At this time, general surgery and urology were consulted.

Fewer than 60 minutes after presentation, the patient began to decompensate. His skin was pale; he appeared in distress and was hypotensive and tachycardic. The colorectal surgeons noted perianal and perineal discoloration with mild bogginess around the hemorrhoid incision, concerning for necrotizing fasciitis. Additional antibiotics and IV fluids were given, and he was scheduled for emergency debridement in the OR. Repeat labs at that time were worse, with lactate >10 and WBC 77. Despite resuscitation, he became tachypneic and hypoxic, requiring emergency intubation, seized and ultimately went into cardiac arrest and died.

Case Conclusion

Upon case review with providers from emergency medicine, colorectal surgery, urology, and critical care, a general consensus was that the patient suffered from pelvic sepsis leading to severe shock with multiorgan failure. Despite aggressive and appropriate sepsis resuscitation, the patient did not make it to the OR for debridement.

The case was accepted by medical examiners for further evaluation. After one month, cause of death was not officially determined, but suspected to be related to surgical site infection. The medical examiner reported negative blood cultures. The pelvic area demonstrated gross and microscopic evidence of infection. There were multiple organisms in the pelvic sample but not yet determined contaminant versus culprit. There was no bacterial growth in the initial blood cultures from presentation after 5 days.

Figure 1: CT Pelvis Axial demonstrating proctitis, free fluid in pelvis

Figure 2: CT Pelvis coronal slice demonstrating proctitis, free fluid in pelvis

During discussion, it was discovered that the colorectal surgeon had placed local anesthetic in the rectum to help with post-operational pain. It is possible that the combination of analgesic and antipyretic medications masked the patient’s initial sepsis symptoms, resulting in a delay of his presentation to the ED.

Discussion

Hemorrhoids are a common cause of anal discomfort and rectal bleeding, with a prevalence of 4% in the population.1 Hemorrhoids are classified as internal or external, based on their location above or below the dentate line, respectively. While external hemorrhoids are often medically managed or excised with an in-office procedure, various surgical treatment options exist for internal hemorrhoids.

The most common complication for excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids include recurrence. Bleeding and swelling are also common. Excision of internal hemorrhoids can come with more severe complications including bleeding, urinary retention, fecal incontinence, sepsis, and rectal perforation.2 Interestingly, prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely prescribed after hemorrhoidectomy, as the risk of infection is assumed to be low and antibiotics do not reduce risk of infection.3

Urologic difficulties and pain are common in post-surgical patients. Many patients experience urinary retention due to pelvic pain.4 A temporary foley may be placed to prevent bladder distension and improve patient comfort. However, persistent urinary retention, dysuria, and unexpectedly severe pain in the genital area should alert the provider to the possibility of more severe post-surgical problems. Lack of urine with foley placement may indicate renal dysfunction. Patients with recurrent or severe complaints should be examined by the urology and colorectal surgery services for further management while in the ED.

Severe perineal or abdominal pain, urinary retention, fever, and leukocytosis could be features of perineal sepsis. Examination of the surgical area can appear normal. Patients may have vague complaints such as pain and constipation. In previous reports, some patients visited the ED more than once with these symptoms before pelvic sepsis was diagnosed.1 Those presenting early with tissue edema and sepsis, but without established tissue necrosis, can be treated conservatively with antibiotics. It is important to note that the absence of gas on CT does not exclude the possibility of gangrene or necrotizing fasciitis. However, those with established necrosis and/or subcutaneous emphysema should undergo urgent debridement of nonviable tissue. Even with surgical debridement, mortality is high.1

Importance of Awareness

Pelvic sepsis is a well-known and feared complication of colorectal and urologic surgery; however, it is not common and may not be recognized by emergency physicians. Patients may present with only mild chief complaints and relatively normal physical exams. Thus it is important to involve surgeons early in these cases and obtain CT imaging. Empiric antibiotics should include those that cover anaerobic organisms; examples of such antibiotics include clindamycin and metronidazole.

This case exemplifies the severity of pelvic sepsis and how it can affect anyone, regardless of age or comorbidities.

References

- McCloud JM, Jameson JS, Scott AN. Life-threatening sepsis following treatment for haemorrhoids: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:748–55.

- Chapter 8. Hemorrhoids. Operative approaches to the treatment of hemorrhoids. In: Colon & Rectal Surgery, 5th ed, Corman ML (Ed), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2005. P.210.

- Nelson DW, Champagne BJ, Rivadeneira DE, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for hemorrhoidectomy: are they really needed? Dis Colon Rectum. 2014 Mar;57(3):365-9.

- Kin C, Rhoads KF, Jalali M, Shelton AA, Welton ML. Predictors of postoperative urinary retention after colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Jun;56(6):738-46.