Point-of-care ultrasound-guided arthrocentesis performed in the emergency department can expedite the diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis, potentially averting the need for surgery.

Source control via aspiration of purulent synovial fluid, when accompanied by intravenous (IV) antibiotics, may provide definitive treatment and therefore reduce the need for surgery and therefore the overall morbidity of the disease. Performing hip arthrocentesis on pediatric patients, however, often requires assembling a multidisciplinary care team and thus may lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment. We report a case of pediatric gonococcal monoarthritis of the hip, for which initial diagnosis and treatment were directed by emergency medicine (EM)-performed POCUS-guided arthrocentesis.

Introduction

Acute septic hip arthritis is a pediatric emergency. Treatment delays may lead to complications including osteomyelitis, osteoarthritis, joint destruction, and systemic illness.1 Most arthrocenteses are performed by interventional radiologists (IR) or orthopedic surgeons.2,3 Using a consult service, however, requires coordination among care teams, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment. Use of POCUS-guided arthrocentesis in the ED supplants the need for a consulting service. Cases reported in the literature of emergency physician-performed POCUS-guided hip arthrocentesis demonstrate decreased time to diagnosis, initiation of antibiotics, and surgical intervention when necessary.4,5

Case

A 16-year-old female with a history of coxa magna deformity of the femoral head and left congenital hip dysplasia was transferred from an outside hospital (OSH) to a pediatric tertiary care facility with fever and atraumatic left hip pain concerning for septic arthritis. The OSH reported fever of 38.5 C, elevated ESR and CRP, leukocytosis, and moderate left hip effusion on MRI. Upon presentation to the ED, the patient was afebrile after being given ketorolac at the OSH but complained of persistent left hip pain. Initial vitals were: heart rate 85, respiratory rate 20, blood pressure 113/62, oxygen saturation 99% on room air. She endorsed three days of subjective fevers with no prior illness and one day of difficulty bearing weight on the affected leg. Her pain was dissimilar to that previously associated with her hip dysplasia. Additional history revealed high-risk sexual behavior with a prior diagnosis of chlamydia cervicitis. She had no history of tick bites, travel to Lyme-endemic areas, rash, or rheumatologic disease.

Physical exam revealed an anxious, nontoxic-appearing female with tenderness to palpation and decreased range of motion of the left hip with no swelling, crepitus, deformity, erythema, or skin breaks. Her preferred position was supine with left hip flexed and externally rotated. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, including normal external genitalia.

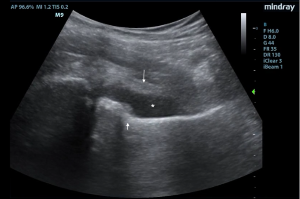

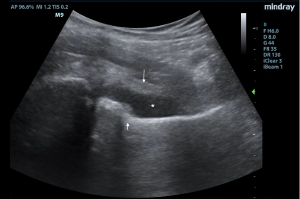

Initial ED course involved IV hydration, analgesia, and labs demonstrating ongoing leukocytosis with left shift, normal coagulation studies, and normal liver and renal function. Urine was sent for N. Gonorrhoeae and C. Trachomatis nucleic acid amplification tests. POCUS examination of bilateral hips revealed a 10 mm fluid collection anterior to the left femoral neck consistent with a hip effusion. Orthopedic surgery was consulted and requested an arthrocentesis, a procedure typically performed by an IR team at this institution, requiring time for transport, team organization, and room set-up. The EM team therefore elected to perform a POCUS-guided arthrocentesis.

Ultrasound Arthrocentesis Technique

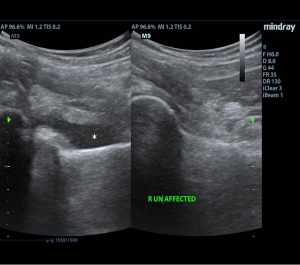

With a linear array transducer positioned transversely over the inguinal region, the location of the femoral neurovascular bundle was marked using a surgical pen. The transducer was then rotated into a sagittal oblique position to visualize the hip effusion, and depth was measured to determine appropriate needle length. A low-frequency curvilinear probe was also briefly used to optimize visualization and to compare bilateral hips (Figures 1 and 2).

Under POCUS guidance, a 22-gauge 3.5-inch spinal needle was inserted distal to the long axis of the linear transducer and lateral to the femoral vessels. The needle was advanced in-plane to enter the anterior synovial recess and 10 ml of blood-tinged, purulent fluid was aspirated. There were no procedural complications and the patient had immediate resolution of pain with improved range of motion.

Synovial fluid was sent for cytology, gram stain, and culture, and was suggestive but not definitive for septic arthritis (WBC 29,000, no pathogens on gram stain). Urine N. Gonorrhoeae later resulted positive which, in combination with aspirate results, prompted initiation of IV ceftriaxone. After source control with successful aspiration, orthopedic surgery attempted conservative treatment for four days in lieu of incision and drainage. Ultimately, however, persistent hip pain and elevated CRP required operative management for definitive treatment.

Discussion

This case illustrates that POCUS-guided hip arthrocentesis by trained emergency physicians can be performed safely and rapidly in the ED, reducing time to diagnosis and treatment by eliminating the need for procedural consulting services. POCUS-guided arthrocentesis directed medical management while culture results were pending and helped initially to avoid arthrotomy, although the patient ultimately required operative management after conservative treatment failed.

POCUS-guided arthrocentesis can be both diagnostic and therapeutic in stable patients with hip effusions, and a substitute for more invasive arthrotomy pending clinical improvement. This minimally invasive procedure is associated with less scarring, shorter hospital stays, and faster return to normal activity.6 To date, no studies demonstrate a difference in clinical outcomes for pediatric patients with septic arthritis undergoing aspiration versus arthrotomy.7-10 In a prospective multicenter treatment study of pediatric osteoarticular infections, however, 50 of 62 children with septic arthritis of the hip were treated successfully with aspiration and antibiotics alone.11 There are also reported successes in treating pediatric septic arthritis of the hip with daily, repeated POCUS-guided aspiration and irrigation.6 Of note, however, the literature cautions that this technique should only be used in previously healthy patients, and no more than five days from symptom onset.10

POCUS-guided arthrocentesis is an efficient and effective method for diagnosis of acute septic arthritis of the hip and, with adjunctive antibiotics, may be used as definitive conservative management.

References

- Plumb J, Mallin M, Bolte RG. The role of ultrasound in the emergency department evaluation of the acutely painful pediatric hip. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(1):54-61.

- Garrison J, Nguyen M, Marin JR. Emergency department point-of-care hip ultrasound and its role in the diagnosis of septic hip a Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(8):555-557.

- Kotlarsky P, Shavit I, Kassis I, Eidelman M. Treatment of septic hip in a pediatric ED: A retrospective case series analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(3):602-605.

- Tsung JW, Blaivas M. Emergency Department Diagnosis of Pediatric Hip Effusion and Guided Arthrocentesis Using Point-of-Care Ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2008;35(4):393-399.

- Minardi J, Denne N, Miller M, Larrabee H, Lander O. Acute arthritis of the hip--case series describing emergency physician performed ultrasound guided hip a W V Med J. 2013;109(5):22-24.

- Givon U, Liberman B, Schindler A, Blankstein A, Ganel A. Treatment of Septic arthritis of the hip joint by repeated ultrasound-guided aspirations. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(3):266-270.

- El-Sayed AMM. Treatment of early septic arthritis of the hip in children: comparison of results of open arthrotomy versus arthroscopic drainage. J Child Orthop. 2008;2(3):229-237.

- Lavy CBD, Thyoka M, Mannion S, Pitani A. Aspiration or lavage in septic arthritis? A long-term prospective study of 150 patients. Orthopaedic Proceedings 2003 Feb (Vol. 85, No. SUPP_II, pp. 109-109). The British Editorial Society of Bone & Joint Surgery.

- Smith SP, Thyoka M, Lavy CBD, Pitani A. Septic arthritis of the shoulder in children in Malawi. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84-B(8):1167-1172.

- Xu G, Spoerri M, and Rutz E. Surgical treatment options for septic arthritis of the hip in children. African J Paediatr Surg. 2016;13(1):1-5.

- Pääkkönen M, Kallio MJT, Peltola H, Kallio PE. Pediatric septic hip with or without arthrotomy: Retrospective analysis of 62 consecutive nonneonatal culture-positive cases. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2010;19(3):264-269.