Meningitis is typically a clinical diagnosis commonly found in younger patients based on symptoms of fever, headache, photophobia, nuchal rigidity, and often with nausea and vomiting.1

The peak incidence occurs in infants and decreases with age.2 A lumbar puncture is ideal to distinguish its etiology; however, most cases of meningitis alone are now caused by enteroviruses.3 Other viruses are implicated based on vaccination status, travel history, or immunosuppression. The following case describes an adolescent male presenting with persistent symptoms after a head injury, who was ultimately found to have HSV meningoencephalitis.

Case

A 12-year-old male was brought to the emergency department by his parents for headache and intermittent fevers that began 13 days prior, now with new symptoms of sleepiness, difficulty standing, and decreased oral intake and urine output. The patient had no past medical history and was allergic to penicillin. Symptoms began one day after a head injury sustained while playing football and included one episode of vomiting. The patient was evaluated twice since symptoms began, had a negative head CT and positive genetic probe strep test, and was discharged with clindamycin.

Physical exam on the third hospital visit revealed an ill-appearing, lethargic 12-year-old male with normal vital signs. Cardiopulmonary exams were unremarkable, and neurologic exam was significant for mild global weakness with normal reflexes, no tremor, and intact cranial nerves and sensation. Skin exam revealed no rashes or diaphoresis.

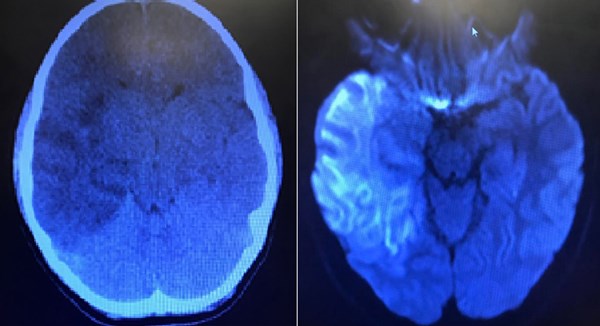

Testing revealed a CBC, BNP, CRP, and fibrinogen within normal limits. Urinalysis was unrevealing for infection. LFTs and ammonia were normal. Blood cultures were drawn. CT of the head showed extensive temporal involvement as well as impending uncal herniation. MRI demonstrated temporal lobe enhancement consistent with HSV encephalitis. The patient was admitted and started on vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir for meningitis coverage. Mannitol was started for osmotic diuresis to lower intracranial pressure. The patient subsequently was taken to the operating room for craniotomy. Brain biopsies were positive for HSV.

Discussion

Herpes simplex virus is the second most common cause of meningitis in adolescents and adults and is often associated with genital lesions.4 In the normal healthy patient, viral meningitis is typically self-limiting and only requires supportive care to manage symptoms and maintain euvolemia.5 However, meningitis may progress to meningoencephalitis, which involves neurologic dysfunction.6 Symptoms range from impaired reflexes and cranial nerves to altered mental status or seizures. HSV encephalitis can be life-threatening and requires timely antiviral therapy.7 Neuroimaging of these patients may or may not reveal abnormalities, however typically temporal lobe lesions are indicative of HSV involvement.8

While most children with viral meningitis recover completely with minimal short-term sequelae, there is limited data on the neurologic prognosis of those who also develop encephalitis.

The diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis requires high clinical suspicion, and not all classic symptoms need to be present. Lumbar puncture is most useful to delineate etiology, however immediate empiric treatment is the best approach to managing these patients.

Case Resolution

The patient remained intubated in the pediatric intensive care unit for nearly two weeks. He regained neurological function, however, was noted to have many deficits. He had a prolonged hospital course without further complication.

Take-Home Points

- Meningitis is a clinical diagnosis; however, invasive diagnostics are required to optimize therapy and lumbar puncture is the gold standard

- Patients concerning for meningitis of unclear etiology should be treated empirically

- Aseptic meningitis is often self-limiting requires only supportive care

- Encephalitis is a distinct entity evidenced by neurologic dysfunction and requires targeted therapy

References

- Tunkel AR, Scheld WM. Acute meningitis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005:1083-126

- Rantakallio P, et al., Incidence and prognosis of central nervous system infections in a birth cohort of 12,000 children. J Infect Dis. 1986; 18(4): 287-94.

- Kupila L, et al. Etiology of aseptic meningitis and encephalitis in an adult population. Neurology. 2006 Jan 10; 66(1): 75-80.

- Abzug MJ. Viral meningitis and encephalitis. In: Current Pediatric Therapy, 18th, Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, Gershon AA (Eds), Saunders, Philadelphia 2006. p.810.

- Sawyer MH, Rotbart H. Viral meningitis and aseptic meningitis syndrome. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, eds. Infections of the central nervous system 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:75-93

- Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex virus. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, eds. Infections of the central nervous system 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:123-44.

- Hindmarsh T, et al. Accuracy of computed tomography in the diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis. Acta Radiol Suppl 369: 192-196.