Some of the most common procedures in the emergency department are painful and anxiety-inducing for patients. Despite a broad spectrum of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, managing procedural pain is complex, stressful, and frequently rushed on a busy shift — and often doesn’t meet the patient’s expectations.

In a perfect world, we would aim to keep patients calm and comfortable, but in real life, managing pain often falls several rungs on the ED hierarchy of needs when genuine life-and-death situations are present, either for the patient whose life is in danger or elsewhere in the department.

The inadequacy of analgesia during ED procedures has been well-documented,1,2,3 and every EM resident can remember examples in which we feel that our plan and execution for pain management failed. It is also helpful to reflect on the fact that the effectiveness of any care in the ED, including procedural pain management, never rests with one person.

Understandably, most patients with painful injuries want pain relief, and they want it now. Aside from people living with chronic pain, the average person simply has not been oriented to the reality that sometimes, nothing can be done by a doctor or nurse to take away all their pain and give them complete relief. For some patients, this disappointment is compounded once we explain that general anesthesia simply is not an option in the ED, and many of us will have heard the phrase “knock me out, doc!” some time before graduating residency.

General guidance is to proactively set expectations and recalibrate to a goal of “tolerable pain.” The best approach to reaching this goal, acknowledging that in the real world we often fall short, may be a combination of systems-level interventions to address persistent gaps, a high standard for team dynamics and communication, and broadening our personalized multimodal procedural pain plans for each patient.

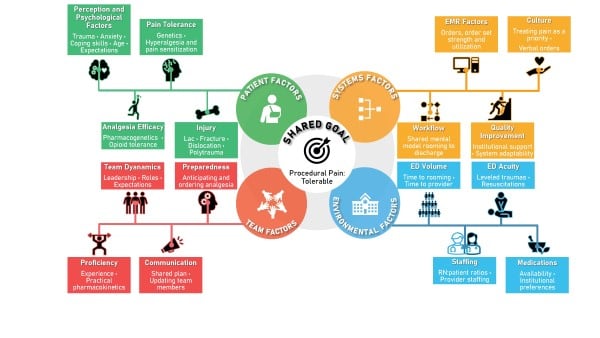

A Model for Procedural Pain Management

If you have ever been disappointed that any of your most proactive, most patient-centered pain management plans ultimately fell short of the goal of “tolerable pain,” there are likely many reasons for this. Many parts of pain management are completely outside of our control (e.g., opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia in patients with chronic pain), while some factors are potentially modifiable through team efforts such as quality improvement initiatives. We created a model of the determinants of procedural pain management strategies (Figure 1) to put into context the much larger framework that poses barriers to achieving tolerable procedural pain.

Figure 1

Patient Factors

Not all injuries are created equal. A patient blessed with strong coping skills with a superficial, linear laceration to the thigh is going to have a better experience with their procedural pain than a polytrauma patient with multiple fractures arriving to the ED after a high-speed motor vehicle collision.

Several non-modifiable patient factors — injury type and complexity, variables contributing to pain tolerance and analgesia efficacy, coping skills, underlying anxiety, psychosocial context of the injury — are meaningful to understand in order to tailor your approach to that patient’s care. Polytrauma patients will likely need IV opioids re-dosed throughout their ED course, along with a thoughtful multimodal approach to specific procedures such as hematoma block for distal radius fracture reduction. Anticipating which patients will be most benefited by nonpharmacologic interventions is helpful as well.

Pediatric patients in particular benefit from well-managed parental anxiety and active parental education and involvement, along with distraction techniques.4,5,6 At our hospital, these nonpharmacological approaches are expertly led by support from a child life team member at the bedside.

Among adults, prior traumatic experiences are associated with dysfunctional pain perception.7 Pain management is more challenging in adult patients with comorbid anxiety and/or challenges with coping skills.8 Such patients, like pediatric patients, are likely to benefit from similar interventions addressing the psychological inputs to their experience of pain. Offering a warm blanket and turning the lights off has helped put many of these patients at ease in our experience. These types of actions build a sense of trust and compassion, and show that the physician is compassionate toward their pain and suffering.

Notably, there is significant variability in patient perception of provider empathy.9 This perception in turn affects patient perception of pain.10 Physicians who self-report higher levels of empathy are actually more likely to be perceived by patients as less caring.11 This is a reminder to us all to be thoughtful in demonstrating and voicing empathy to our patients, as one of the non-pharmacological adjuncts to managing procedural pain.

Keep in mind as well that patients living with chronic conditions such as fibromyalgia or chronic pain are likely to have undergone very real biological rewiring, creating a state of central pain sensitization and hyperalgesia.12 Some of these patients may be chronic users of prescription opioids, so anticipate both a tolerance effect for opioid analgesia during their procedure along with an even greater reliance on non-opioid analgesia such as ketorolac.

For all patients, expectation setting is critical. We have had great experience with being direct about a shared goal of “tolerable pain” very early into the ED encounter. It is often apparent from the doorway which patients will require painful ED procedures, and engaging about this topic sooner rather than later gives the patient an opportunity to process the expectation, ask questions, and ultimately feel as satisfied as possible that our plan for managing their pain is thoughtful and offers them the best relief possible outside of what can be achieved in the operating room.

Team Factors

No emergency physician is an island. Procedural pain management success hinges on a shared plan between the physician and the nurse. The physician’s role, in many ways, is to offer a well-informed plan and then empower the nurse to execute it in real time as the patient’s pain evolves before, during, and after a painful procedure.

For example, lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine (LET) for laceration repairs can be ordered immediately after the patient is roomed, to be available for the nurse at any time after the initial physician assessment. For more complex injuries, thoughtful ordering of PO acetaminophen vs. ibuprofen, IV ketorolac, and/or IV analgesia PRNs as soon as possible after patient rooming improves efficiency as well as the patient experience.

Once a plan is created and shared with the nurse, and medications are ordered and available, team communication and dynamics become important for effective procedural pain management. Getting to know and build trust with nursing colleagues improves every kind of care that we provide in the ED, and pain management is an excellent example of this. Updating the nurse about estimated time to procedure start is crucial if the plan involves IV hydromorphone, with time to peak effect as long as 20 minutes. Appropriate updates also empower the nurse to be available at procedure start, either to directly support the procedure or, at minimum, to check on the patient and offer last-minute insights that strengthen the plan.

Unlike patient factors, the majority of team factors included in our model are directly modifiable, specifically by the physician leading the team. While these factors are generally intuitive, high-level team management insights are not at the forefront of anyone’s mind on a busy shift. Reflecting on what we can do better as team leaders gives us the opportunity to be proactive and improve.

Environmental Factors

There are often real-world barriers that even a great team with a great plan will have difficulty overcoming.

For example, the higher the patient:provider and patient:RN ratio, the less focus and attention each patient will receive, unfortunately. Nurses report that staff shortages are a direct contributor to inadequate pain management.13

Higher ED volumes and acuity levels are factors as well.14,15 ED team members and resources are finite, and a critical polytrauma patient or resuscitation elsewhere in the department will pull team members away from other patients.

Another environmental factor to consider is the immediate availability of procedural pain management medications, which is likely to vary from ED to ED. Availability of medications is, of course, also contingent upon nursing availability.

Environmental factors are by their nature difficult to modify and require large-scale change, particularly in addressing staffing.

Systems Factors

The ED is an intuitive home for systems-level process improvements. Our work environment is fast-paced and unpredictable, necessitating emergency physicians and our co-workers to be responsive, adaptable, and efficient.

High-volume ED procedures in particular are amenable to quality improvement work, with prior successes including reducing time to analgesia and improving pain scores.16,17 An EM resident will learn early into training that most patients presenting to the ED with painful injuries and requiring procedural care will experience similar trajectories in their pain with common analgesia needs, varying by injury complexity and other factors.

A patient’s experience with procedural pain management is highly likely to be influenced by systems factors. One example of this is the EMR, particularly order-set utilization. Order sets and protocols for multimodal pain management have been found to improve pain management, promote non-opioid analgesia, and decrease opioid analgesia needs.18,19,20

Other systems factors that are more difficult to address include unit culture toward pain management,21 such as whether nursing is empowered to advocate for individual patients who may not have adequate analgesia prior to starting procedures. An example in which culture (systems factor) and dynamics (team factor) intersect is the use of verbal orders, which has the potential to save time by allowing a nurse to administer analgesia by verbal order only. Understandably, nurses encounter many scenarios in which they may not be comfortable accepting verbal orders, and EM nursing publications have commented on this.22 An ED culture most supportive of verbal orders is best cultivated through compliance with guidelines for verbal orders including closed loop communication23,24,25 and strong relationships between physicians and nurses.

Procedural Pain Management Tools

Speaking of improvement, one way that you — as an EM resident-physician practicing right now — can improve your own procedural strategy and success is to become as comfortable as possible with all the options available for pain management in the ED.

We spoke with our RN pool about these topics and have included their insights here to provide depth from the perspectives of ED team members who most closely manage pain at the bedside.

Depending on your training environment and culture, you may already use LET to its full potential every day, or it may not even be stocked in your ED. When we surveyed our nursing colleagues about areas for improvement in procedural pain management, the very first response was an enthusiastic “LET is king!” This came from one of our most experienced ED RNs. LET does need time to get the job done, so remember not to rush royalty. You may already be a stickler for ensuring medication administration at an appropriate amount of time before beginning a procedure, or you may feel so rushed when you’re ready to start that laceration repair that you find yourself impatient and wondering if you really need to wait a few extra minutes to allow medications to take peak effect.

Other food for thought gathered from our ED RNs includes overwhelming support for IV acetaminophen. Data in the literature, however, is mixed and primarily focused on post-operative pain. Some studies support IV acetaminophen efficacy over PO,26 particularly with reducing time to peak effect.27 Some studies found no difference between the two routes.28,29,30 We encourage you to do what you think is best for your patients in your own experience.

Another common insight: Setting expectations is everyone’s job. Our ED RNs recommended that this be considered a team effort in which physicians and nurses express the same messaging and compassion to the patient.

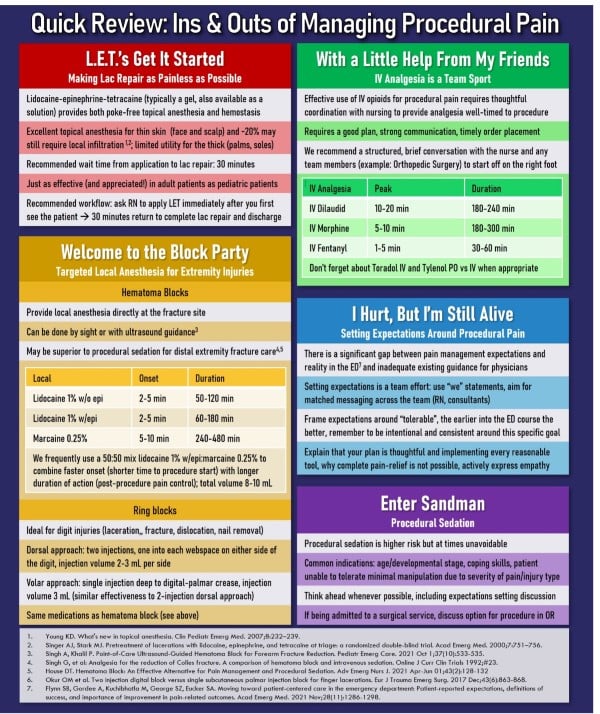

We have put together a summary of medications for managing procedural pain in the ED (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Conclusion

Effective pain management is challenging under any circumstances, particularly for patients presenting to the ED with painful injuries. Many factors contribute to how patients experience and manage pain during procedures. Some factors are more immediately modifiable, such as intentional and strategic use of available pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to pain management. Other factors are higher level, difficult to influence on the ground, and potential targets for quality improvement interventions.

There is always room for growth, particularly around recurring gaps and systems issues that can be tackled through multidisciplinary team efforts. In your daily practice, set yourself up for success with a good plan, strong standards for team communication and dynamics, and healthy expectations setting.

Editor’s note: EMRA provides additional resources for pain management in the ED, including the EMRA and AAED Nerve Blocks and Procedural Pain Management Guide and the Pain Management Guide, 1st Edition. These publications, and others, can be purchased via the EMRA Store and Amazon.

References

- Brown J, Klein E, Lewis C, et al: Emergency Department analgesia for fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42:197.

- Cimpello L, Khine H, Avner J: Practice patterns of pediatric versus general emergency physicians for pain management of fractures in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004;20(4):228.

- Minick P, Clark PC, Dalton JA, Horne E, Greene D, Brown M. Long-bone fracture pain management in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2012 May;38(3):211-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2010.11.001. Epub 2011 Mar 23. PMID: 21435705.

- Oommen S, Shetty A. Does parental anxiety affect children's perception of pain during intravenous cannulation? Nurs Child Young People. 2020 May 6;32(3):21-24. doi: 10.7748/ncyp.2019.e1187. Epub 2019 Oct 28. PMID: 31657172.

- Sağlık DS, Çağlar S. The Effect of Parental Presence on Pain and Anxiety Levels During Invasive Procedures in the Pediatric Emergency Department. J Emerg Nurs. 2019 May;45(3):278-285. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2018.07.003. Epub 2018 Aug 16. PMID: 30121121.

- Pancekauskaitė G, Jankauskaitė L. Paediatric Pain Medicine: Pain Differences, Recognition and Coping Acute Procedural Pain in Paediatric Emergency Room. Medicina (Kaunas). 2018 Nov 27;54(6):94. doi: 10.3390/medicina54060094. PMID: 30486427; PMCID: PMC6306713.

- Tsur N, Defrin R, Shahar G, Solomon Z. Dysfunctional pain perception and modulation among torture survivors: The role of pain personification. J Affect Disord. 2020 Mar 15;265:10-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.031. Epub 2020 Jan 13. PMID: 31957687.

- Craven P, Cinar O, Madsen T. Patient anxiety may influence the efficacy of ED pain management. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Feb;31(2):313-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.08.009. Epub 2012 Sep 13. PMID: 22981626.

- Howick J, Steinkopf L, Ulyte A, Roberts N, Meissner K. How empathic is your healthcare practitioner? A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient surveys. BMC Med Educ. 2017 Aug 21;17(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0967-3. PMID: 28823250; PMCID: PMC5563892.

- Vangronsveld KL, Linton SJ. The effect of validating and invalidating communication on satisfaction, pain and affect in nurses suffering from low back pain during a semi-structured interview. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(2):239–46.

- Katsari V, Tyritidou A, Domeyer PR. Physicians' Self-Assessed Empathy and Patients' Perceptions of Physicians' Empathy: Validation of the Greek Jefferson Scale of Patient Perception of Physician Empathy. Biomed Res Int. 2020 Feb 12;2020:9379756. doi: 10.1155/2020/9379756. PMID: 32104709; PMCID: PMC7037872.

- Carriere JS, Martel MO, Meints SM, Cornelius MC, Edwards RR. What do you expect? Catastrophizing mediates associations between expectancies and pain-facilitatory processes. Eur J Pain. 2019 Apr;23(4):800-811. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1348. Epub 2019 Jan 9. PMID: 30506913; PMCID: PMC6420376.

- Shoqirat N, Mahasneh D, Singh C, Al-Sagarat AY, Habashneh S. Barriers to nursing pain management in the emergency department: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019 Oct;25(5):e12760. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12760. Epub 2019 Jul 12. PMID: 31297927.

- Zachodnik J, Andersen JH, Geisler A. Barriers in pain treatment in the emergency and surgical department. Dan Med J. 2019 Feb;66(2):A5529. PMID: 30722824.

- Sills MR, Fairclough DL, Ranade D, Mitchell MS, Kahn MG. Emergency department crowding is associated with decreased quality of analgesia delivery for children with pain related to acute, isolated, long-bone fractures. Acad Emerg Med. 2011 Dec;18(12):1330-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01136.x. PMID: 22168199.

- Chang HL, Jung JH, Kwak YH, Kim DK, Lee JH, Jung JY, Kwon H, Paek SH, Park JW, Shin J. Quality improvement activity for improving pain management in acute extremity injuries in the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2018 Mar 30;5(1):51-59. doi: 10.15441/ceem.17.260. PMID: 29618194; PMCID: PMC5891748.

- Woolner V, Ahluwalia R, Lum H, Beane K, Avelino J, Chartier LB. Improving timely analgesia administration for musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department. BMJ Open Qual. 2020 Jan;9(1):e000797. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000797. PMID: 31986116; PMCID: PMC7011892.

- Chasle V, de Giorgis T, Guitteny MA, Desgranges M, Metreau Z, Herve T, Longuet R, Farges C, Ryckewaert A, Violas P. Evaluation of an oral analgesia protocol for upper-limb fracture reduction in the paediatric emergency department: Prospective study of 101 patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019 Oct;105(6):1199-1204. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.06.009. Epub 2019 Aug 22. PMID: 31447399.

- Bornstein E, Husk G, Lenchner E, Grunebaum A, Gadomski T, Zottola C, Werner S, Hirsch JS, Chervenak FA. Implementation of a Standardized Post-Cesarean Delivery Order Set with Multimodal Combination Analgesia Reduces Inpatient Opioid Usage. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 22;10(1):7. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010007. PMID: 33375192; PMCID: PMC7793107.

- Horton JD, Corrigan C, Patel T, Schaffer C, Cina RA, White DR. Effect of a Standardized Electronic Medical Record Order Set on Opioid Prescribing after Tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Aug;163(2):216-220. doi: 10.1177/0194599820911721. Epub 2020 Mar 17. PMID: 32178580.

- Sampson FC, O'Cathain A, Goodacre S. How can pain management in the emergency department be improved? Findings from multiple case study analysis of pain management in three UK emergency departments. Emerg Med J. 2020 Feb;37(2):85-94. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2019-208994. Epub 2019 Dec 12. PMID: 31831588.

- Paparella S; ENA's ED Safety Workgroup. Avoid verbal orders. J Emerg Nurs. 2004 Apr;30(2):157-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2004.01.014. PMID: 15039674.

- Joint Commission International Center for Patient Safety. 2008 Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals. Available at: http://www.jcipatientsafety.org/15148/

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. (2015). Recommendations to reduce medication errors associated with verbal medication orders and prescriptions. http://www.nccmerp.org/recommendations-reducemedication-errors-associated-verbal-medication-orders-and-prescriptions.

- Standards on verbal orders rank high among common compliance problems. ED Manag. 2009 May;21(5):suppl 1-2. PMID: 19552346.

- Politi JR, Davis RL 2nd, Matrka AK. Randomized Prospective Trial Comparing the Use of Intravenous versus Oral Acetaminophen in Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017 Apr;32(4):1125-1127. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.10.018. Epub 2016 Oct 21. PMID: 27839957.

- Nichols DC, Nadpara PA, Taylor PD, Brophy GM. Intravenous Versus Oral Acetaminophen for Pain Control in Neurocritical Care Patients. Neurocrit Care. 2016 Dec;25(3):400-406. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0289-z. PMID: 27351176.

- Sun L, Zhu X, Zou J, Li Y, Han W. Comparison of intravenous and oral acetaminophen for pain control after total knee and hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Feb;97(6):e9751. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009751. PMID: 29419667; PMCID: PMC5944691.

- Johnson RJ, Nguyen DK, Acosta JM, O'Brien AL, Doyle PD, Medina-Rivera G. Intravenous Versus Oral Acetaminophen in Ambulatory Surgical Center Laparoscopic Cholecystectomies: A Retrospective Analysis. P T. 2019 Jun;44(6):359-363. PMID: 31160871; PMCID: PMC6534170.

- Antill AC, Frye SW, McMillen JC, Haynes JC, Ford BR, Bollig RW, Daley BJ. Treatment With Oral Versus Intravenous Acetaminophen in Elderly Trauma Patients With Rib Fractures: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Am Surg. 2020 Aug;86(8):926-932. doi: 10.1177/0003134820940268. Epub 2020 Aug 4. PMID: 32749863.