The first-ever Emergency Medicine Wellness Week™ was observed this January. It was a good opportunity to take stock of wellness on a personal, program-based, and profession-wide level. Any resident worth a salary knows that ignoring our own fallibility is a good way to end up in trouble. This got me thinking about my own psychological well-being and the techniques I use to protect it.

Psychological well-being is something we preach. We've studied the DSM, interviewed PTSD patients, seen “vicarious trauma” as an option on written exams. Yet, despite shifting paradigms (even the Armed Forces now recognize that “suck it up” is not often a valid response to personal suffering), health care workers often view themselves as psychologically invincible. We get uncomfortable at the thought of being susceptible to the same psychological ailments as our patients.

Most of us have been spent at least 10 years and hundreds of thousands of dollars on higher education. We've delayed other parts of our lives, we've sacrificed, and we know how to be tough — sometimes too tough and too self-sacrificing.

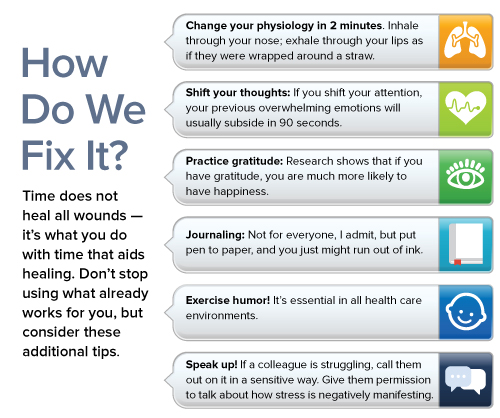

Suicide rates among medical students, residents, and staff physicians are alarming. Depression, substance abuse, and marital disharmony are also present in the ranks. Yet our own mental health continues to be the elephant in the room. Learn to recognize in yourself the same red flags you would note in a patient, and have a management strategy at the ready should you need it.

This is hard; most of us are Type-A personalities who view struggling as a weakness. We frown on “touchy-feely” sentiments and set aside both small and large stressors. It's akin to having chest pain on a run, ignoring it, having chest pain at rest, ignoring it, getting sweaty and pale while having chest pain one morning, ignoring it, and then”¦you get the idea. There is no strength or intelligence in waiting to fall apart.

Compassion Fatigue in Health Care

When we stop being nice to ourselves, our colleagues, and our patients, something is seriously wrong. It indicates a process that leads to hypo- and hyper-arousal during crises and results in underperformance. Compassion fatigue makes us susceptible to vicarious trauma, PTSD, and suicidal ideation. Signs include negativity, diminished tolerance for ambiguity, intrusive thoughts about difficult patient situations, dread of going on shift, anger, depression, absenteeism, and organic illness.

Conclusion

Your mental health is extraordinarily important; refresh your memory of the services available to you through your employer (e.g., employee assistance plans, extended health benefits, and wellness services), your school (e.g., resident affairs offices and social supports), and your communities. Residency should be an enjoyable and healthy part of your life and lead you to prosper in your profession, your relationships, and your own sense of wellbeing.

So, to all my fellow Type A's, be the BEST at self-care. Or nothing else will matter.