Nausea and vomiting are major chief complaints in the emergency department, accounting for around 2.5 million annual ED visits.1

While the majority of these cases are due to innocuous etiologies such as gastritis, GERD, etc., EM physicians are trained to rule out the potential life-threatening causes such as acute coronary syndrome (ACS), aortic dissection, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), increased intracranial pressure, esophageal ruptures, small bowel obstruction, appendicitis, torsion, and ectopic/ruptured ectopic pregnancies.

In the pediatric population, the differential also includes things such as pyloric stenosis, intussusception, and non-accidental trauma (NAT). When considering cardiac causes of nausea and vomiting in young adults, ACS would be quite uncommon, and most would not routinely include congestive heart failure (CHF) high on the differential, making it an important talking point.

Case Summary

An 18-year-old otherwise healthy female presented with a chief complaint of nausea and vomiting. These symptoms had been ongoing for the past 2-3 weeks, along with intermittent abdominal pain. Additionally, she reported multiple episodes of emesis per day and could barely keep down water at that time. When she presented to the ED, she mentioned that she lost 30 pounds over the past 2-3 weeks. She denied any chest pain, shortness of breath, fevers, or chills. Her last menstrual period was 3 weeks prior. She was sent in by her primary care physician for further evaluation of her vomiting and weight loss due to the duration of her symptoms.

Initial vital signs noted tachycardia of 130 bpm, blood pressure (BP) of 85/33, pulse ox of 100% on room air, respiratory rate of 18, and she was afebrile at 98.1°F. Initial EKG showed sinus tachycardia of 116 bpm. On the initial physical exam, the patient was noted to be tachycardic. She also had bilateral 1+ edema of the legs to the knees. Her lungs were clear, and her heart was tachycardic but regular. Her abdomen was soft, non-distended, and non-tender.

Notably, during the patient's ED stay she never complained of chest pain or shortness of breath. She attributed her tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting to being anxious at the time.

Resuscitation was started with 2L of 0.9% NS and anti-emetics as noted below. The patient was placed on a cardiac monitor. IV access was obtained, along with labs including a septic workup. Blood work revealed a CBC with normal hemoglobin and a normal white count. CMP was notable for a glucose of 68, magnesium of 1.2, direct bilirubin of 0.4, and a lactate of 2.1. Lipase was normal and a beta hCG quant was negative. Urinalysis was negative for UTI but did show 50 ketones. Magnesium was replenished in the emergency department.

Our differential included PE, appendicitis, colitis, and dehydration. The patient was unresponsive to these fluids and remained hypotensive and tachycardic, so we ordered a CT angiogram for PE and CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast.

In the department, the patient was given diphenhydramine, metoclopramide, ondansetron, and magnesium for nausea and electrolyte abnormalities. CT imaging revealed severe cardiomegaly and right heart strain.

On reassessment, the patient's vitals were 97/72, pulse of 104, and respiratory rate of 15 breaths/minute. Upon obtaining CT results, a bedside limited echo was performed. This revealed significantly reduced EF as well as grossly dilated heart. The global left ventricular function was significantly reduced. Cardiology was called to the bedside, and a formal stat echo was consistent with the bedside echo. This revealed EF <10% and possible left ventricular non-compaction. Given echo findings and a new diagnosis of cardiomyopathy and persistent hypotension, there was a concern for cardiogenic shock, and milrinone was initiated. The patient was subsequently admitted to Cardiac ICU.

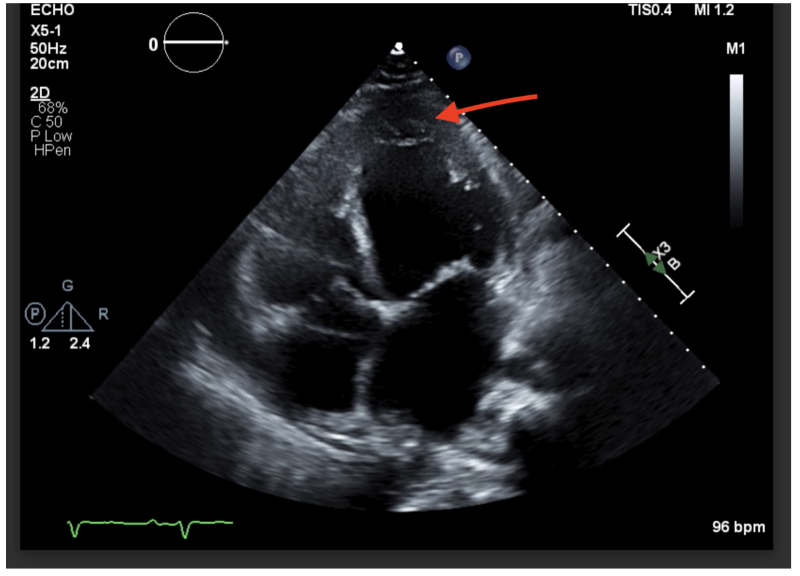

Image 1: Non-compaction in the left ventricle. In this image, you can see the non-compacted trabeculae in the apex of the left ventricle. This non-compaction was the cause of our patient’s acute congestive heart failure.

Image 1: Non-compaction in the left ventricle. In this image, you can see the non-compacted trabeculae in the apex of the left ventricle. This non-compaction was the cause of our patient’s acute congestive heart failure.

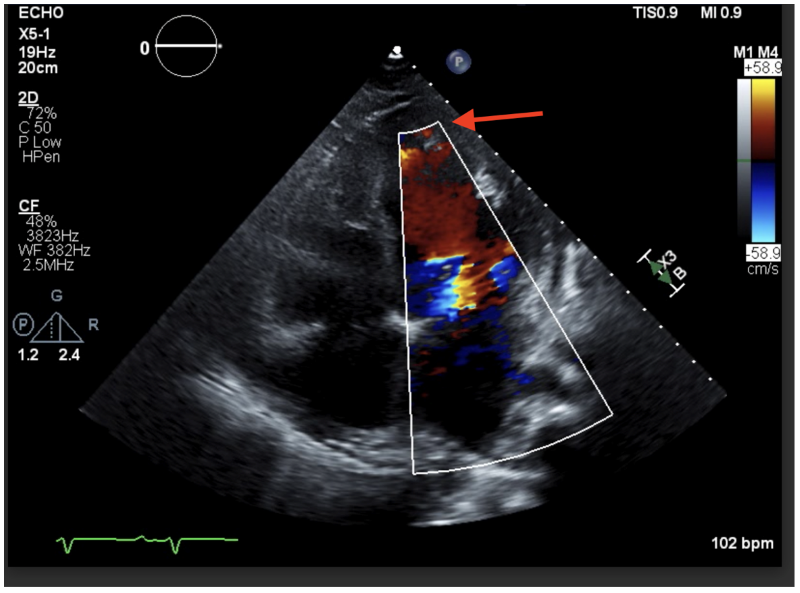

Image 2: This color Doppler ultrasound image shows those same trabeculae at the apex.

Image 2: This color Doppler ultrasound image shows those same trabeculae at the apex.

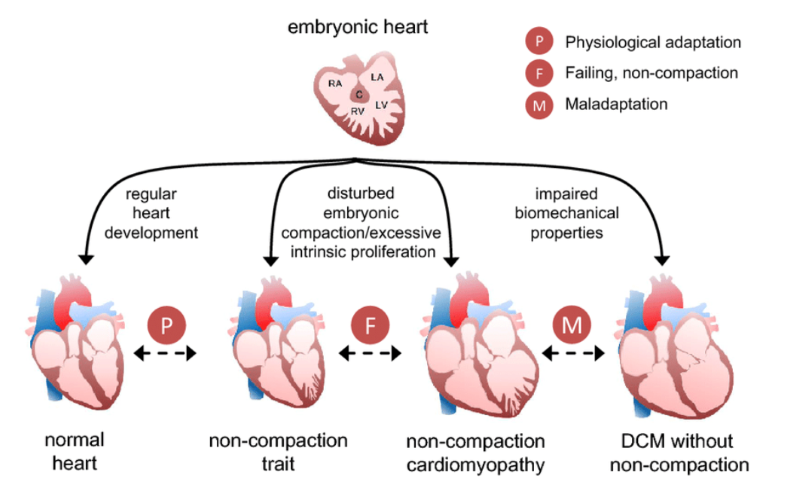

Image 3: Embryonic development of the heart and the trabeculae seen with noncompaction cardiomyopathy (NCCM).8

Image 3: Embryonic development of the heart and the trabeculae seen with noncompaction cardiomyopathy (NCCM).8

Our patient spent 10 days in the hospital for new onset decompensated heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Cardiology, Rheumatology, and Infectious Disease teams were consulted on her case. Additional testing/workup included a respiratory viral panel, which was negative, and an autoimmune workup for possible hypothyroid-induced dilated cardiomyopathy and viral myocarditis – both of which were also negative. Gastroenterology stated the nausea and vomiting were secondary to volume overload and a pericardial effusion. A cardiac MRI showed non-compaction cardiomyopathy involving the left and right ventricles with global enlarged chambers and hypokinesis. Mitral and tricuspid regurgitation and a moderate-sized pericardial and small pleural effusion were also noted. Prior to discharge, the patient was started on guideline-directed medical therapy (empagliflozin), furosemide, losartan, spironolactone, metoprolol, and a Life Vest. She was referred to the heart failure clinic for follow-up at an outside hospital.

Case Conclusion

One month after her initial presentation, the patient was placed on the transplant list, as her cardiac function had not recovered with medical management. She successfully underwent a cardiac transplant 3 months later and has been doing well since then.

Discussion

Noncompaction cardiomyopathy (NCCM) is a type of cardiac disorder that is believed to occur during embryogenesis. The thought is that this arises from a failure of compaction of the ventricle during ventricular formation. During development, there is a 2-layered ventricular wall: one layer has a thin epicardial surface and a second inner layer has trabeculations that are not compacted. The trabeculae are associated with recesses that communicate with the ventricular cavity but not the circulation of the coronaries.2

NCCM was recognized as a distinct cardiomyopathy in 2006 and has an incidence of 0.12/100k patients or 12 in 10 million patients.3 There are 2 distinct age ranges of presentation: those in the first few years of life and those in adulthood.4 It is the third most common cardiomyopathy in children (after dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), with most children being diagnosed before 1 year of age. Diagnosis in adults is most often triggered by an abnormal EKG or echo. It is also believed there is a significant familial component to these patients and that inheritance can be either autosomal dominant or X-linked, which has been seen in a small group of patients.4

Complications can include tachydysrhythmias that can worsen heart failure symptoms in pediatric patients. In adults, NCCM often causes syncope. Additionally, there is a risk of thromboembolic events as clots can be formed in the honeycomb structure, similar to clots from stasis of atrial fibrillation. Treatment is aimed at tachydysrhythmias and anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy. The first-line treatments are beta-blockers or ACE inhibitors. As with many cardiomyopathies, once a patient reaches end-stage heart failure, a transplant is the best option for resolution. In North America, 4% of children on the heart transplant list carry a diagnosis of NCCM.5 Presenting symptoms in adults include dyspnea, palpitations, chest pain, syncope or presyncope, and prior stroke.6

Literature Review

In a small retrospective study performed at a children's hospital in Turkey involving 29 patients, presenting symptoms seen in children include heart failure symptoms (69%), murmur (10%), chest pain (7%), and asymptomatic (7%).7

In the case report by Capin et al., a 7-year-old male presented several times during a 3-week period to the ED. This patient's symptoms were noted to be fatigue and suicidal ideation, which progressed to diffuse abdominal pain. He was placed in the ICU and started on a BiVAD due to the severity of the disease. The treatment of this patient was also a heart transplant.8

Through our literature research, we saw small sample sizes, with presentations happening mostly in the first years of life or later in life in adulthood. Many of the patients who present with this cardiomyopathy present in the early stages of life, rarely in early adulthood. Additionally, when an otherwise healthy 18-year-old woman presents to the ED with nausea and vomiting, congestive heart failure is not immediately on the differential but should be considered, and POCUS can help evaluate for this as well as other causes of hypotension.

References

- Porras N, Wipple T, Kim H. Anti-emetics/Gastroparesis. NUEM Blog. 2020.

- Almeida AG, Pinto FJ. Non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2013;99(20):1535-42.

- Rohde S, Muslem R, Kaya E, et al. State-of-the art review: Noncompaction cardiomyopathy in pediatric patients. Heart Fail Rev. 2022;27(1):15-28.

- Yates L. Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC). Australian Genetic Heart Disease Registry. Undated.

- Fox SM. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy in children. Pediatric EM Morsels. December 10, 2021. Accessed July 9, 2023.

- Bhatia NL, Tajik AJ, Wilansky S, Steidley DE, Mookadam F. (2011). Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricular myocardium in adults: a systematic overview. J Card Fail. 2011;17(9), 771–778.

- Ozgur S, Senocak F, Arman Orun U, Ocal B, Karademir S, Dogan V, Yilmaz O. Ventricular non-compaction in children: Clinical characteristics and course. Interact Cardiovasc Thoracic Surg. 2011;12(3):370-373.

- Capin I, Capone CA, Taylor MD. Acute on chronic heart failure secondary to left ventricular noncompaction. Case Rep Pediatr. 2020;2020:6369806.

Additional Reading

- Cincinnati Children’s. Left Ventricular Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy (LVNC). Accessed July 9, 2023.

- Kayvanpour E, Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Gi WT, et al. Clinical and genetic insights into non-compaction: a meta-analysis and systematic review on 7598 individuals. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108(11)1297–1308.