The rise in heroin and opioid overdoses throughout the country demands an awareness of the sequelae of naloxone-related pulmonary edema that can occur in opiate overdose reversal.

Case Description

A 32-year-old male visiting from out of state was brought in by EMS after a friend found him passed out in the bathroom. The patient was given 8 mg of Narcan by EMS with no response and the patient arrived in the ED with EMS using a bag-valve mask to assist in respiration.

Initial vital signs were HR 116, RR 22 (by EMS), SpO2 86%, and BP 118/80. Shortly after arriving in the ED, with no further intervention, the patient became awake, alert, oriented, and began speaking in full sentences. Repeat vital signs were HR 103, SpO2 94%, and BP 125/66. The patient admitted to marijuana, cocaine, and IV heroin use. The physical exam was pertinent for an alert patient with dried blood in the bilateral nares and with equal and reactive dilated pupils. The patient was tachycardic, but in normal rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. His pulmonary exam was significant for initially slow, but then normal respiratory rate, with rhonchi bilaterally, and he had an unremarkable abdominal and extremity exam. Once the patient became alert, no focal neurological deficits were noted.

Initial laboratory work was significant for a leukocytosis with WBC 14.28, and a toxicology screen positive for benzodiazepines, cocaine, cannabinoids, and opiates. His initial lactic acid was 5.7, the Basic Metabolic Panel was significant for a potassium level of 5.5, and his blood gas on arrival was pH 7.34/PaCO2 48/PaO2 97.

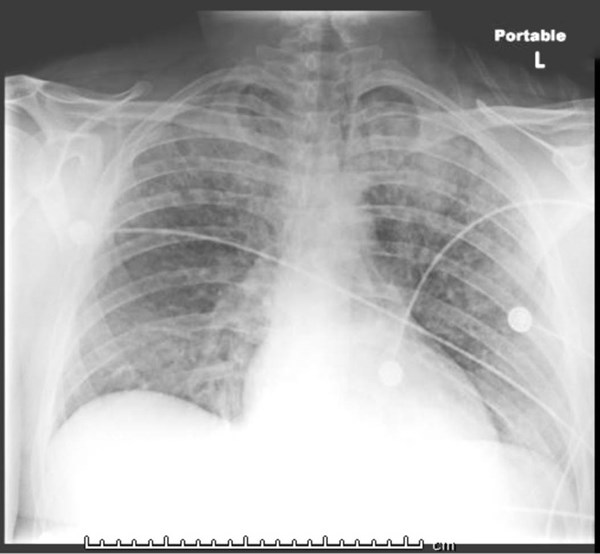

While being observed in the ED, the patient’s SpO2 began to decrease to the low 90s. Repeat ABG demonstrated a developing respiratory acidosis with pH 7.21/PaCO2 66/PaO2 65. A chest X-Ray revealed bilateral patchy infiltrates, concerning for ARDS. He was placed on bipap, with initial improvement in oxygen saturation. However, when the patient was evaluated by the MICU team, he was in increasing respiratory distress, and the decision was made to intubate. Per ARDS protocol, the patient was placed on the ventilator with low tidal volumes and high PEEP, and he was admitted to the MICU.

During his third day following ARDS protocol on mechanical ventilation, the patient developed pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the setting of worsening hypoxemia. The patient was placed on nitric oxide treatment overnight as a bridge to ECMO. His respiratory failure did not respond to inhaled nitric oxide, paralysis, or to steroid treatments. He underwent multiple bronchoscopies for mucous plug removal, and cultures showed evidence of Pasteurella bacterial infection, indicating aspiration pneumonia. He continued to clinically deteriorate with worsening hypoxemia, and on day 5 of admission, he was placed on V-V ECMO.

After 4 days of ECMO therapy, he was successfully weaned off, and he was extubated 5 days later. The patient was discharged home 6 days later with no oxygen requirements and in a stable condition.

Discussion

The literature on the subject of non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema and that regarding ARDS in the context of opiate overdose reversal is slowly developing; however, the explanation is most likely multifactorial. While animal studies have discussed the effects of Narcan on pulmonary capillary permeability and the phenomenon of pulmonary edema, robust literature has not well described the phenomenon in humans.1,2 Some of the theories suggest that a catecholamine release occurs after opioids are reversed by Narcan, leading to a rapid increase in cardiac output and pulmonary pressures, ultimately increasing the risk for ARDS. Other theories describe leaking of pulmonary capillaries and subsequent accumulation of protein-rich pulmonary fluid also increasing the risk for ARDS. The negative pulmonary pressures that result from an upper airway obstruction, due to obstructive secretions or mucous plugs, a closed glottis, or glottis laxity, can also complicate the issue.3

The most common etiologies for ARDS include sepsis, aspiration, near-drowning, pneumonia, and barotrauma. In our case, bronchoscopy cultures showed evidence of Pasteurella bacteria, suggesting aspiration pneumonia as a precipitating cause of the patient’s ARDS. It is important to realize, however, that ARDS can result independent of aspiration in this population as well.

A case series conducted over 4 years by Sporer and Dorn analyzed 27 patients who developed non cardiogenic pulmonary edema within 24 hours of their presentation for heroin overdose. 74% of these patients were hypoxic on arrival to the emergency department and 22% developed symptoms of respiratory distress within the first hour. While 33% of patients required mechanical intubation, the majority were able to be extubated after 24 hours. In order to optimize a patient’s respiratory status in the setting of opioid induced noncardiogenic pulmonary, endotracheal intubation should be considered early in the course of presentation.4

The use of ECMO in patients with refractory hypoxemia on mechanical ventilation secondary to opiate overdose is rarely needed. Yet, as we have seen in this case report, it can be a lifesaving alternative when a patient is failing standard ARDS treatment on mechanical ventilation.

ARDS requiring ECMO in opiate-overdose patients is becoming an increasingly recognized treatment strategy. A recent case report describes a similar case requiring V-A ECMO for ARDS secondary to aspiration pneumonia after an opioid overdose.2 In another case study from Egypt, a patient with ARDS secondary to opiate overdose was successfully weaned off V-V ECMO and extubated after 12 and 14 days, respectively. Similar to our case, both patients were successfully discharged without supplemental oxygen requirements.5,6 Therefore, it is important to note that, similar to other recommendations in ARDS treatment, transfer to an ECMO center should be considered in the case of opioid-induced ARDS refractory to mechanical ventilation.

References

1. Mills CA, Flacke FW, Flacke WE, et al. Narcotic reversal in hypercapnic dogs: comparisonof naloxone and nalbuphine. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37;238.

2. Silverstein JH, Gintautas J, Tadoori P, Abadir AR. Effects of naloxone on pulmonary capillary permeability. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;328;389-392.

3. Busti A, Hinson J, Regan L. Mechanism for Naloxone-Related Pulmonary Edema in Opiate or Opioid Overdose Reversal. Evidence-Based Medicine Consult. August 2015.

4. Sporer K, Dorn E. Heroin Related Non – cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema: A Case Series. Chest. 120(5);2001. 1628-1632.

5. Said AA, Khaled M, Abdalfattah A, Ahmen A. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in a case of opioid-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Egyptian J Crit Care Med. 4(1);2016.39-42.

6. Greenberg K, Kohl B. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation used successfully in a near fatal case of opioid-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(2):343.