Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is an autoimmune neuromuscular disorder characterized by the formation of autoantibodies against postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction resulting in fluctuating weakness of the extraocular, bulbar, limb, or respiratory musculature.

Myasthenia Gravis is the most common disorder of neuromuscular transmission.2 The prevalence of MG in the United States is estimated to be 37 per 100,0003 with estimated incidence ranging from 4.1 to 30 cases per million person-years.4 The disease most commonly presents in females under the age of 40 and men over the age of 60. MG may present at any age in either sex, although it is rare in children.3 MG has a strong association with thymic hyperplasia and thymoma. It is estimated that 13% of patients with MG have one or more co-existing autoimmune diseases, most commonly affecting the thyroid gland. There is an estimated rate of co-occurrence of 7% with Graves disease and 3% with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, which may contribute to symptoms of ophthalmopathy and weakness if present.5

Most patients initially present with intermittent flares of ptosis, extraocular muscle weakness, and diplopia. The second most common presentation involves bulbar muscle weakness, which can present in the form of dysphagia, dysarthria, and frequent aspiration.6 A key feature in diagnosis is weakness that worsens with repeated muscle use and improves with rest, which explains the symptom correlation as typically better in the morning and worse in the evening. Left untreated, weakness may spread and become generalized. In severe flares, known as myasthenic crisis, the diaphragm and accessory muscles of breathing may become significantly weak, requiring noninvasive positive airway ventilation or intubation with mechanical ventilation. For this reason, prompt diagnosis and initiation of treatment are vital for individuals experiencing their first MG flare.

Case Presentation

This patient is a 52-yo male with past medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia who presented to the ED with approximately one month of progressive bilateral ptosis and one week of progressive bilateral diplopia and photophobia. The patient reported that these symptoms were more noticeable later in the day and worsened with reading and typing. The patient’s gaze disturbance was first noted by his wife, and the patient agreed to be evaluated by an optometrist. The patient was seen and instructed to report to the ED for concern of neuromuscular or intracranial pathology. After an unremarkable initial workup at an outside ED which included head CT/CTA, basic blood work, chest radiograph, and ECG, the patient was transferred to our tertiary care center for further neurological evaluation.

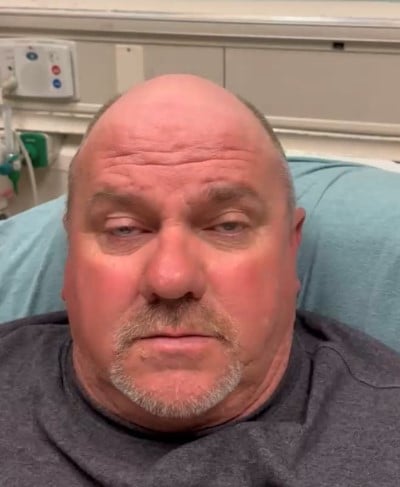

The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits aside from mildly elevated blood pressure. Review of systems was positive for headache, diplopia, and photophobia. The patient denied recent fever, seizures, vertigo, limb weakness, stiffness, or pain. Reassuringly, the patient denied having any respiratory complaints. On physical exam, the patient exhibited bilateral ptosis (Image 1).

Image 1. Bilateral ptosis found on exam

Extraocular range of motion was intact, but he had some difficulty with vertical gaze, which was easily fatigable and accompanied with noticeable compensation by the frontalis muscle (Image 2). Additionally, he had marked photophobia, which prevented pupillary light reflex testing due to the patient squeezing his eyelids tightly in response to bright light. The patient was unable to effectively complete visual field testing due to diplopia.

Image 2.

The remainder of his physical exam, including his neurologic exam, was unremarkable. Due to concern for MG based on his history and exam, the ice pack test was performed. A plastic bag was filled with ice and held over his eyes for 2 minutes (Image 3).

Image 3.

The ice pack was then removed with noticeable improvement of symptoms and exam, including resolution of his ptosis (Image 4). Vertical gaze improved (Image 5), and the patient reported resolution of diplopia and photophobia.

Image 4.

Image 5.

Pupillary light reflex was assessed and found to be normal. This effect lasted for approximately 90 seconds before ptosis reappeared. The test was conducted twice, approximately 15 minutes apart, with identical results, and the presumptive clinical diagnosis of MG was made.

The patient was admitted for additional neurological work-up and diagnosis confirmation. Blood samples were sent to an outside lab to check for the presence of anti-acetylcholine and anti-MuSK antibodies. Soon after arriving on the floor, the patient was evaluated by the staff neurologist who agreed with our diagnosis and initiated prednisone and pyridostigmine. A chest CT was unremarkable for any thymic or respiratory abnormalities and brain MRI was similarly unremarkable. Approximately 24 hours after first arriving in the ED, the patient reported that his symptoms had greatly improved, and on repeat exam, exhibited no ptosis or vertical gaze deficit.

Discussion

The mechanism of ptosis in myasthenia gravis is believed to be due to the inhibition of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle at its lower motor neuron synapse with the oculomotor nerve. This is caused by the blockade of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by autoantibodies. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the temporary improvement of ocular MG symptoms after cooling.1 Although colder temperatures have been demonstrated to decrease the speed of nerve conduction,7 they also inhibit the action of acetylcholinesterase, resulting in a greater amount of neurotransmitter for a longer period to be present in the gap junction. This mechanism is also applied in the use of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor pyridostigmine as first-line treatment for myasthenic flares.6

In addition to pyridostigmine, immunosuppression with glucocorticoids or azathioprine are indicated for acute myasthenic flares. Second-line immunosuppressive agents include methotrexate and cyclophosphamide. For patients experiencing myasthenic crisis, IVIG or plasmapheresis are indicated due to their rapid onset to prevent respiratory collapse. Thymectomy is recommended in patients with evidence of thymoma, seronegative disease, or anti-nicotinic-Ach subtype of disease if presentation occurs between the ages of 15 and 50.6

The initial diagnostic workup for patients with MG symptoms should include a complete neurological exam as well as imaging to rule out stroke or intracranial mass, which may present with similar symptoms. Patients should also undergo CT or MR imaging of the thymus as well as measurement of thyroid stimulating hormone to investigate concomitant autoimmune thyroid disease. Differential diagnosis may include disorders of the neuromuscular junction or the peripheral nervous system such as Lambert-Eaton syndrome, botulism, Horner syndrome, neuromyotonia, or Guillain-Barre syndrome. Diagnosis may be confirmed by nerve conduction study or by the presence of anti-acetylcholine or anti-MuSK antibodies, although a small percentage of patients are seronegative.8 Historically, checking for symptom improvement in response to intravenous edrophonium, a short-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, was seen as the gold-standard diagnostic test for MG, often called the Tensilon test,1 but it has since been supplanted by serologic and nerve conduction studies due to the concern for serious side effects including bradycardia and bronchospasm. The ice pack test has proven to be an effective initial method of diagnosis for ocular MG. When used to detect MG in patients presenting with diplopia, ptosis, or both, the ice pack test has been reported to demonstrate a sensitivity of 76.9% and a specificity of 98.3%.9 The authors of this study found the study to remain highly specific, even in patients with co-existing thyroid dysfunction.

Conclusion

Patients presenting with their first MG flare require prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression of symptoms. The initial diagnosis of MG is largely clinical, as confirmatory serologic testing such as Anti-AcH and Anti-MuSK serologic testing may take several days to result, and treatment should not be withheld for such confirmatory testing. In this patient’s case, ice-pack testing could have easily been done at the first ED visit. A correct presumptive diagnosis was made quickly at our facility which allowed for confirmatory and prompt initiation of appropriate treatment. With maintenance immunosuppression, the prognosis of individuals with ocular MG is good, with most living a normal life expectancy with minimal disability.8

References

- Marinos E, Buzzard K, Fraser CL, Reddel S. Evaluating the temperature effects of ice and heat tests on ptosis due to Myasthenia Gravis. Eye (Lond). 2018;32(8):1387-1391.

- Rubin M. Disorders of Neuromuscular Transmission - Neurologic Disorders. Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Merck Manuals, 1 Sept. 2022. Accessed 7 August 2023.

- Bubuioc A-M, Kudebayeva A, Turuspekova S, Lisnic V, Leone MA. The epidemiology of myasthenia gravis. J Med Life. 2021;14(1):7-16.

- Dresser L, Wlodarski R, Rezania K, Soliven B. Myasthenia Gravis: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2235.

- Mao Z-F, Yang LX, Mo XA, et al. Frequency of autoimmune diseases in myasthenia gravis: a systematic review. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121(3):121-129.

- Beloor Suresh A, Asuncion RM D. Myasthenia Gravis. StatPearls Internet. StatPearls Publishing. 7 Dec 2022. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

- Foldes FF, Kuze S, Vizi ES, Deery A. The influence of temperature on neuromuscular performance. J Neural Transm. 1978;43(1):27-45.

- Sieb JP. Myasthenia gravis: an update for the clinician. Clin Exp Immunol. 2104;175(3):408-18.

- Chatzistefanou KI, Kouris T, Iliakis E, et al. The ice pack test in the differential diagnosis of myasthenic diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2236-2243.