A 7-year-old Caucasian male presented to the pediatric ED with a chief complaint of

persistent frontal headache for 1 week. He had no history of prior headaches with vomiting or migraines. His parents reported increasing sleepiness, fatigue and weakness over the past week.

Associated symptoms included body aches, intermittent non-bloody/non- bilious emesis, and decreased oral intake. The parents reported no fevers, upper respiratory infectious symptoms, vision problems, focal weakness, gait instability, or recent travel, trauma, or sick contacts.

Parents said he was diagnosed with giant congenital melanocytic nevi at birth and had an MRI of his brain at 2 months of age showing neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) but was lost to follow- up at 6 months of age. He was seen at an outside facility 2 days prior and had unremarkable lab work and a negative head CT scan. Vital signs showed that he was bradycardic with a heart rate of 30-60/min and hypertensive with BPs ranging between 120s-130s/80- 90s mmHg. He was afebrile and had normal respirations. He was awake, alert, and oriented x 3 but appeared uncomfortable.

Neurologic examination revealed left lower extremity clonus with no other focal or cranial nerve deficits. Fundoscopic examination showed no papilledema. He had a large nevus covering most of his back and neck, as well as several smaller hyperpigmented patches on the extremities.

CBC, BMP, and urine and serum drug screens were unremarkable, except for mild hyponatremia. EKG showed sinus bradycardia, and chest X-ray was negative. Cardiology was consulted and he was admitted to the PICU with concern for elevated intracranial pressure, as hypertension and bradycardia suggested Cushing's reflex.

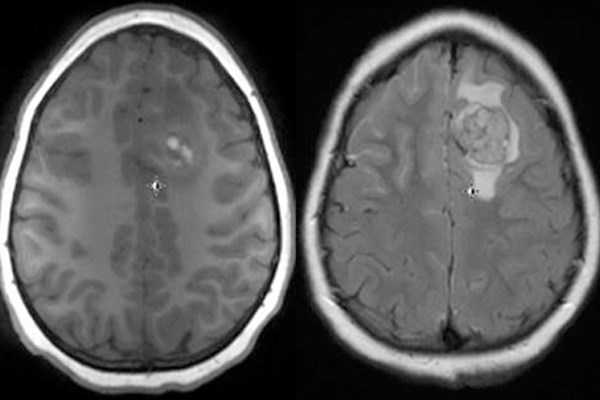

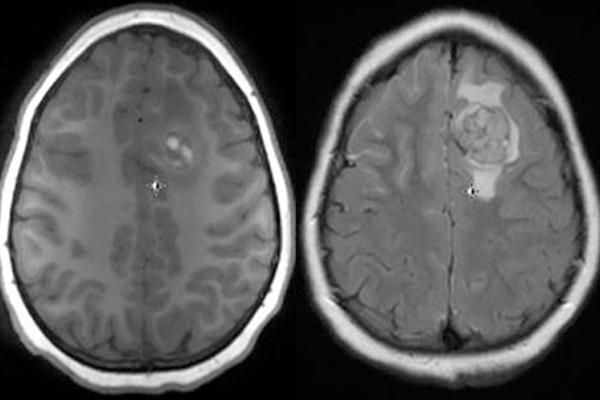

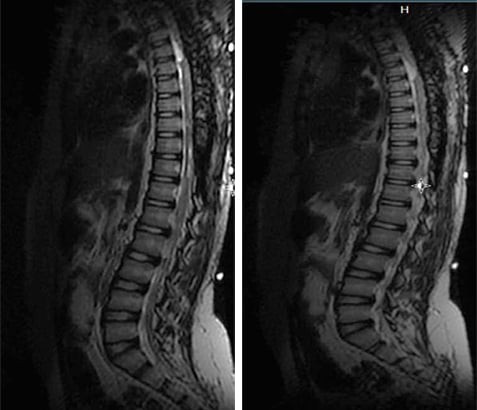

Emergent MRI scans of the brain and spine were obtained, revealing multiple linear and nodular lesions with extensive leptomeningeal enhancement with diffuse craniospinal melanomatosis suggestive of NCM.

MRI of the brain shows nodular area with hyperintense (T1 signal) in the left frontal lobe with surrounding edema consistent with metastatic lesion and significant diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement.

MRI of the spine shows diffuse intradural enhancement, nodular lesions at T2-T3, and abnormal signal at multiple levels, suggesting craniospinal melanomatosis with neurocutaneous melanosis.

He underwent debulking surgery to alleviate spinal cord compression. Pathological evaluation confirmed malignant transformation. Two months later, he developed paraplegia and was started on chemotherapy for residual malignancy. He was found to have multiple CNS recurrences and, despite aggressive therapy, died 6 months later.

Discussion

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are nevi (moles) that are either present at birth or arise within the first few weeks of life. They vary in size from small to very large (> 20 cm) or even giant (> 50 cm). The major medical concern with giant CMN is the high risk of developing cutaneous or leptomeningeal melanoma and/or neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM). Giant lesions are commonly found along the back and trunk, usually sparing the head and extremities, resulting in its classical descriptive terms: bathing trunk nevus, cape nevus, and garment nevus.

Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a rare, non-inherited condition characterized by melanocytic nevi affecting both the skin and brain. Patients with large CMN on the posterior axis or multiple lesions are at increased risk for developing NCM. This condition usually presents within the first 5 years of life, but may present at 7-10 years of age. Intracranial hypertension manifests as seizures, decreased mentation and cranial nerve dysfunction. Symptomatic NCM carries a poor prognosis — median survival is 6 months and median age of death is 5 years.

Children with risk factors for NCM should be screened regularly using MRI.