Liquid nitrogen is used as a food or drink additive to provide rapid cooling or produce a smoky aesthetic effect. Although potentially dangerous and currently unregulated, it has gained popularity in recent years and is used to make cocktails, cool ice cream, and create snacks for children in order to enhance presentation and consumer appeal. As demonstrated by this case of a child who developed pneumoperitoneum secondary to liquid nitrogen ingestion, providers should be aware of this popular additive that may have deadly sequelae.

Case

A 9-year-old female with no significant past medical history arrived to the ED via fire rescue shortly after ingesting “dragon breath” ice cream purchased on a popular pedestrian street. Her mother stated she had ingested the liquid left over at the bottom of the cup. Her parents, who witnessed the event, reported she immediately experienced pain, gripping her abdomen and seeming to have trouble breathing. A bystander believed the patient to be choking and performed the Heimlich maneuver with minimal relief in symptoms. Fire rescue was then called and transferred the patient to the emergency department in stable condition.

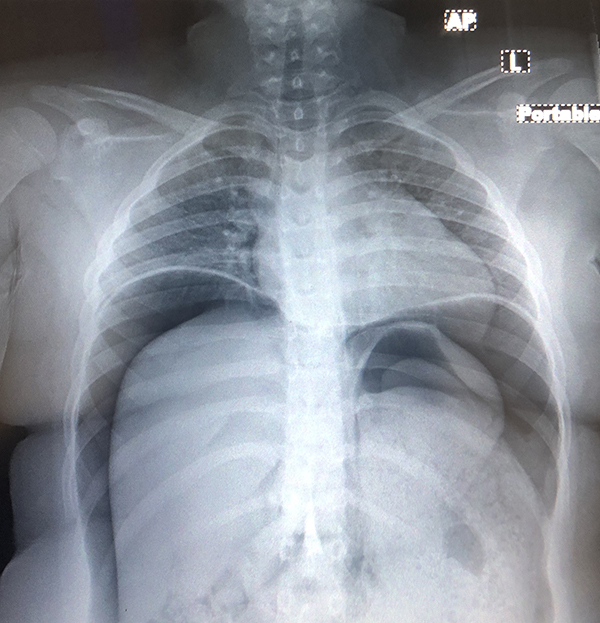

Upon arrival the patient continued to complain of abdominal pain. On examination she was hemodynamically stable but lethargic and responsive to verbal stimuli. Initial vital signs were temperature of 98.1 °F (36.7 °C), heart rate 85 bpm, blood pressure 120/83, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. The patient weighed approximately 54 kilograms. The patient was placed on a cardiac monitor and end tidal carbon dioxide for continued monitoring. She exhibited a distended abdomen which was tympanic, rigid and tender to palpation in the epigastric region. There were no visible signs of trauma or burns along the face, abdomen or anterior chest wall. Lung sounds were clear to auscultation bilaterally. A portable chest x-ray demonstrated extensive pneumoperitoneum (Figure 1), highly suspicious for organ perforation. Laboratory results were significant for a white blood cell count of 16,400 /uL, a potassium level of 3.3 MMOL/L, and a lactic acidosis of 2.5 MMOL/L. Remaining complete blood count, chemistry and toxicology screen were unremarkable.

Figure 1. Portable upright chest x-ray demonstrating massive pneumoperitoneum.

While in the emergency department the patient remained lethargic and exhibited multiple episodes of non-bloody, non-bilious emesis. Treatment was initiated with intravenous fluids, 20 mg famotidine, 1 g of ceftriaxone and 8 mg of zofran. The patient was promptly transferred to a separate pediatric facility where she was intubated for airway protection and taken to the operating room for exploratory laparoscopy. The procedure was converted to open laparotomy for better exposure, and a 3-4 cm full thickness perforation was identified along the lesser curvature of the stomach near the gastroesophageal junction. This area was repaired via Graham patch closure. The patient was extubated the following day and had a two week course in the pediatric intensive care unit complicated by fever attributed to aspiration pneumonia and treated with cefepime, vancomycin, fluconazole and metronidazole. She was discharged on oral antibiotics and followed up in the outpatient clinic with no further complications.

Discussion

This case demonstrates liquid nitrogen to be a potentially fatal substance if directly ingested. Even if promptly treated, solid organ perforation may have a high morbidity and mortality. Prior case reports involving liquid nitrogen detail similar presentations in both adults and children with sudden onset abdominal pain and shortness of breath after ingestion,1-4 with the exception that our patient additionally presented with marked lethargy and altered mental status. Further, prior case reports also identified gastric perforation at the lesser curvature of the stomach as in this case.

Liquid nitrogen has an extremely low boiling point of -196˚C and an expansion ratio of 1:694.1 Proposed mechanisms of injury involve the accumulation of liquid nitrogen in the stomach, which causes damage by thermal burn to the epithelium or via barotrauma due to the rapid volume expansion within the stomach causing rupture at anatomical regions which are particularly susceptible to barotrauma.3,5 The lesser curvature of the stomach is held in place by the hepatogastric ligament, possibly causing further traction on the gastric wall and facilitating gastric rupture at this site in the context of rapid volume expansion secondary to liquid nitrogen ingestion. As in this case, other cases reported no esophageal or oropharyngeal chemical burns with ingestion despite its potential to cause severe frostbite. This can be attributed to the Leidenfrost effect, wherein a liquid encounters a temperature significantly higher than its boiling point and creates a protective vapor layer that slows thermal transfer.6

Interestingly, this patient presented with altered mental status, initially suggesting another diagnosis such as accidental alcohol intoxication. The nitrogen may have caused displacement of oxygen and subsequent hypoxemia leading to altered mental status.5

Take-Home Points

In our case the child did well while ingesting the ice cream covered with liquid nitrogen. It was the act of drinking the remaining pooled liquid containing higher concentrations of liquid nitrogen that caused immediate pain and organ rupture. For emergency medicine specialists it should be noted that such pediatric behavior is normal, just as a child might drink the remaining milk from a cereal bowl. Thus, such natural behavior increases the risk of caustic injury to this population with such toxic ingestions.

Considering the potentially lethal effects of liquid nitrogen ingestion, we suggest the implementation of regulations for the use and purchase of foods with liquid nitrogen additives. Liquid nitrogen as a food additive is gaining more popularity within American culture and emergency physicians should be aware of this rare yet potentially fatal presentation.

References

1. Pollard JS, Simpson JE, Bukhari MI. A lethal cocktail: gastric perforation following liquid nitrogen ingestion. BMJ Case Rep. 2013:bcr2012007769.

2. Walsh MJ, Tharratt SR, Offerman SR. Liquid nitrogen ingestion leading to massive pneumoperitoneum without identifiable gastrointestinal perforation. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(5):607-609.

3. Zheng Y, Yang X, Ni X. Barotrauma after liquid nitrogen ingestion: a case report and literature review. Postgrad Med. 2018;130(6):511-514.

4. Kim DW. Stomach Perforation Caused by Ingesting Liquid Nitrogen: A Case Report one the Effect of a Dangerous Snack. Clin Endosc. 2018;51:381-383.

5. Koplewitz BZ, Daneman A, Fracr S, et al. Gastric perforation attributable to liquid nitrogen ingestion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):121-123.

6. Berrizbeitia LD, Calello DP, Dhir N, O'Reilly C, Marcus S. Liquid nitrogen ingestion followed by gastric perforation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(1):48-50.