And in the end, when the life went out of him and my hands could work no more, I left from that place into the night and wept — for myself, for life, for the tragedy of death’s coming.

Then I rose, and walking back to the suffering-house forgot again my own wounds for the sake of healing theirs.

–Anonymous

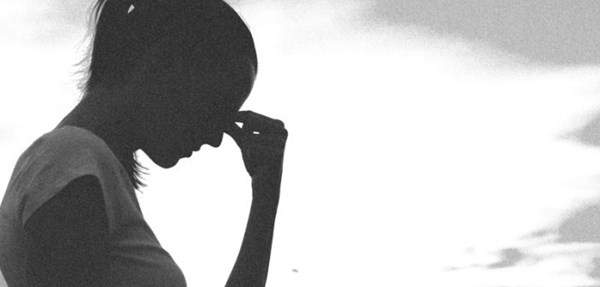

A picture is worth a thousand words. So too was the photograph that went viral on Reddit over a year ago, when an emergency physician took a moment to step outside on a desolate winter night to weep about the loss of his 19-year-old patient. The cold wind must have blown through the thread of his white coat that evening the way the words “Your son died” froze his parents’ hearts.

These types of losses never get easier. The ones who come in talking, and the children, are the hardest. Unforgettable, really. And even worse, one of these will be someone you have unintentionally hurt. You may even think you alone were responsible for their death. The medication you ordered, the procedure you performed, or the diagnosis you failed to make will have been the last thing that patient experienced.

I had my day this past year. A delay in diagnosis followed by a peri-intubation arrest, and there was no going back. Despite reassurance by my colleagues that there was not much else that could have been done, I was crushed. I cried the entire way home. I couldn’t sleep for days. The chaotic scenario played out over and over in my head. And then over again. To this day, when I close my eyes, I can see the blood stains on my scrubs, and the blood draining out of her husband’s face.

What kind of impact do these experiences have on emergency providers? Fatal errors and those that cause harm are known to haunt healthcare professionals throughout their lives. Those who suffer in this way are called second victims and can often experience depression, long-lasting feelings of guilt and shame, loss of confidence, and burnout – which is one reason why physicians are twice as likely as the general population to commit suicide.

The reality is that in the era of modern medicine, there is very little room for error. The more precise and accurate our tests, the less willing we are to allow mistakes. Our own expectation for perfection, combined with incredibly advanced technology, imaging, and life-saving pharmaceuticals, have contributed to this unrealistic present-day intolerance.

Of course, there is still beauty and triumph in modern medicine. During that same devastating shift, I gave tPA to a man who had what would otherwise have been a debilitating stroke, intubated with video laryngoscopy, and used point-of-care ultrasound to diagnose a retinal detachment.

Yet one bad experience can permanently taint our passion for medicine and negatively impact our ability to care for the next patient, either that day, or for days to come. While we must take care of the patients and families who are harmed by medical errors, and strive to make systematic changes to prevent these types of errors from happening, we must also care for the practitioners involved in these errors.

So when I read about a fatal valproic acid overdose that was accidentally managed as a diphenhydramine overdose (p. 10), or about a great save when a critical left circumflex artery occlusion was suspected in the absence of ST-elevations on ECG (p. 22), I can’t help but think about the providers who were there at the bedside, making life-or-death decisions with limited time to act, and with limited information.

The Reddit photo of the weeping emergency medicine physician went viral because it highlighted the fact that doctors are, in fact, human. But the superhuman ability to compartmentalize and bury normal reactions to tragic situations cannot be upheld indefinitely. What few people may have considered, and what we all know too well, is that this emergency physician then composed himself, walked back into the ED, and introduced himself to the next patient with a handshake and a smile. And that patient would never know he had just been to the gates of hell and back.