Aortoiliac occlusive disease, otherwise known as Leriche syndrome, mostly affects older individuals with classic risk factors for peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Although typically a progressive disease, it has been less commonly seen to cause sudden onset critical limb ischemia like in our patient. It is important for the clinician to have a high suspicion for this pathology, consider a patient’s risk factors, relevant medical history, and maintain a wide differential when performing the workup.

Introduction

Leriche syndrome, otherwise known as aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) is due to severe atherosclerosis affecting the distal abdominal aorta, iliac arteries and femoro-popliteal vessels. Risk factors are the same as those for atherosclerosis and include hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLD), hyperglycemia, elevated homocysteine, smoking, age, and family history.1 There can be a wide range of symptoms, from being asymptomatic to intermittent claudication to a triad of claudication, impotence, and absence of femoral pulses.1 Leriche syndrome is often progressive in onset as the thrombus slowly grows, with time for development of collateral vasculature. Thus, it is not very common to see Leriche syndrome resulting in sudden onset critical limb ischemia without prior symptoms, as is seen with this case. Our patient had held their oral anticoagulation prior to the event for an orthopedic procedure, which possibly triggered thrombus formation and sudden limb ischemia.

Case Presentation

We present a case of a female in her eighties with an extensive medical history, including congestive heart failure, nonobstructive coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnea, atrial fibrillation, left bundle branch block, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) placement, left atrial appendage thrombus, transient ischemic attack, polymyalgia rheumatica, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was recovering from a trigger finger surgery that occurred earlier that morning. She presented at 1 am with acute onset bilateral lower extremity burning pain starting at 11:30 pm, when she got out of bed to go to the bathroom. This quickly progressed to complete motor and sensory loss of both lower extremities.

The patient denied any trauma and per family was in her usual state of health when she went to bed earlier that night. On initial examination, the patient appeared in severe distress with cold and mottled bilateral lower extremities. In the ED, providers were unable to find Doppler-able pulses of her lower extremities bilaterally. She endorsed no sensation in bilateral lower extremities up to her proximal thighs and had no motor function in either leg. The patient did have rectal tone but possible fecal incontinence as there was stool in the diaper.

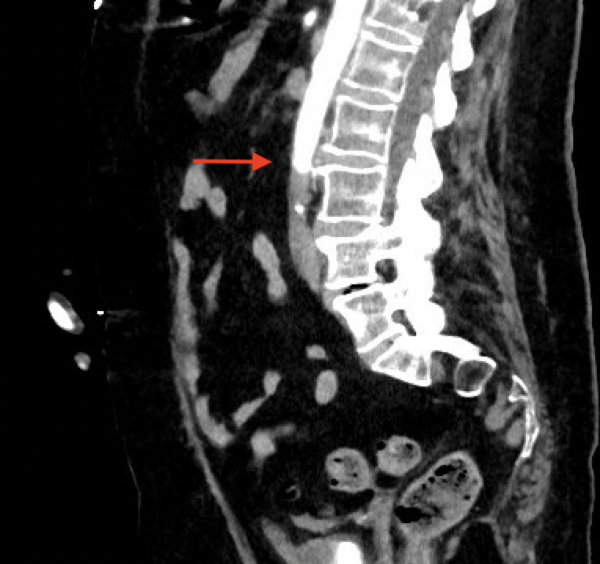

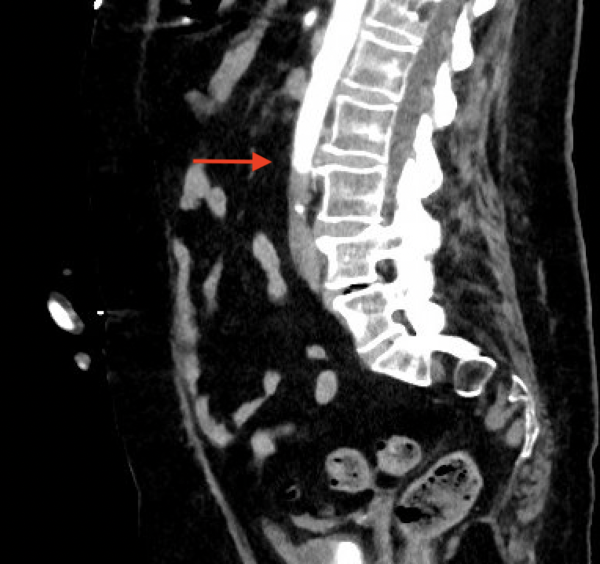

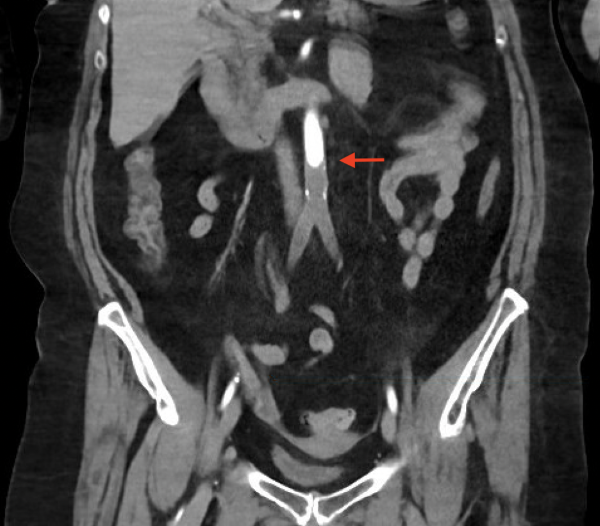

There was an immediate concern for an aortic catastrophe. She was taken for expedited CT angiography (CTA) after IV insertion and pain control. The CTA showed complete occlusion of the infra-renal abdominal aorta and bilateral internal iliacs with preserved external iliacs and 1 vessel run-off to the right lower extremity, 2 vessel run-off to left lower extremity and left renal infarct (Figures 1 and 2).

CTA from 4 months prior showed a patent aorta and iliac arteries without disease. Vascular Surgery was paged, and she was taken immediately to the operating room for emergent revascularization. She went to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) after aorto-bilateral iliac suction thrombectomy, left common femoral artery cutdown and patch angioplasty, bilateral 4 compartment fasciotomies with resolution of thrombus and restoration of flow seen on angiogram.

Her postoperative course was complicated by stress cardiomyopathy leading to cardiogenic shock and reperfusion syndrome with resultant multiorgan failure requiring significant inotropic and pressor support, worsening lactic acidosis, and multiple electrolyte derangements. A goals of care discussion was held with the family by the intensive care and surgery teams, and a DNR order was placed. The patient passed away roughly 48 hours after her initial arrival to the emergency department.

Discussion

Our patient’s clinical presentation was consistent with the most severe end stage clinical manifestation of this disease, as she had lower extremity paralysis, non-palpable lower extremity pulses, and complete occlusion of the infra-renal abdominal aorta and bilateral internal iliac arteries. Per chart review from a primary care visit in 2021, she denied complaints of leg claudication. She had an official diagnosis of HLD, however, not of PAD with no prior documentation in the chart of ankle-brachial index measurements or symptoms consistent with a PAD diagnosis. Prior computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis from May 2023 showed a patent aorta and iliac arteries without disease; however, this was not a dedicated CT Angiography study. It is possible she was having symptoms that went unnoticed for many years. It is also possible she developed significant collaterals to compensate as many patients are asymptomatic because of the development of collateral networks.2 This makes it difficult to determine the exact incidence and prevalence of this condition.

Our patient also had a history of atrial fibrillation and had paused her Xarelto for the past 10 days in preparation for her trigger finger surgery that occurred that morning. An acute thromboembolic occlusion of the distal aorta and iliac arteries is more consistent with acute limb ischemia than chronically worsening peripheral artery disease. Per Wooten et al., 80% of these acute occlusions originate in the heart, and 70% of these cardiac emboli are caused by atrial fibrillation.2 Diagnostic imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation presenting with acute thromboembolic occlusion resulting in critical limb ischemia also revealed the occlusion to be of the distal infrarenal aorta at the bifurcation point (similar to how our patient presented).3 Both the pathology of the limb ischemia itself as well as the complications resulting from management, renal failure, fasciotomies, amputations, cardiomyopathy and electrolyte derangements, result in significant pre and post procedure mortality.4,5

While this is a diagnosis that requires rapid intervention, it is still important to consider other vascular pathology when initially evaluating patients presenting with symptoms of aortoiliac occlusive disease. These include arterial aneurysm, arterial dissection, embolism, Giant cell arteritis and Takayasu, arteritis, and venous claudication.6

Conclusions

In summary, aortoiliac occlusive disease is an overall rare presentation but one with high mortality that requires prompt diagnosis and intervention. Strongly consider this in the differential diagnosis with cases ranging from absent lower extremity pulses to intermittent claudication. Remember to review past medical history to determine risk factors that could predispose to this vascular abnormality and be sure to involve vascular surgery consultants as soon as possible when Leriche Syndrome is suspected.

References

- Brown KN, Muco E, Gonzalez L. Leriche Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Feb 13]. In. StatPearls [Internet, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing:2023.

- Wooten C, Hayat M, du Plessis, et al. Anatomical significance in aortoiliac occlusive disease. Clin Anat. 2014;27:1264-1274.

- Ali AA, Hussein AM, Kanpalta AH, Ahmed SA, Dirie AMH, Keilie AMW. A successful surgical management and outcome for a young man with infrarenal aortoiliac occlusion: A rare case report of Leriche syndrome. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;98:107550.

- Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

- Mohamed A, Mattsson G, Magnusson P. A case report of acute Leriche syndrome: aortoiliac occlusive disease due to embolization from left ventricular thrombus caused by myocarditis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21:220.

- Heaton J, Khan YS. Aortoiliac Occlusive Disease. [Updated 2022 Jun 11]. In. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing:2023.