Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pattern of abusive behaviors against a victim perpetrated by someone who is, or was, in an intimate relationship with the victim.1

Human trafficking (HT) is “the use of force, fraud, or coercion to compel a person into commercial sex acts or labor or services against his or her will.” Inducing a minor into commercial sex is considered HT regardless of the presence of force, fraud, or coercion.2

IPV and HT are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Many victims will seek medical care, often in the ED. This puts emergency physicians in a position to identify and help victims get the help they need to escape these dangerous situations.

In this pilot study, we evaluated the effectiveness of resident education on identifying and appropriately managing victims of IPV and HT in the ED. We assessed residents’ abilities to utilize appropriate resources to help these patients. We also gauged residents’ comfort level in managing these patients after receiving our pilot curriculum. As measured by our pre- and post-survey data, residents expressed significant improvement in knowledge about IPV and HT, as well as higher comfort level in assessing these patients. Our hope is that this pilot project will provide a strong foundation for future projects and strengthen resource availability and utilization for these vulnerable populations.

Introduction

For those experiencing IPV or HT, interaction with the healthcare system may be their only opportunity to seek help. Unfortunately, most healthcare workers have little training on how to identify and help these patients. Studies demonstrate that healthcare professionals are not comfortable with diagnosis and management for a variety of reasons including lack of standardized screening, confusion about their role in management, and lack of awareness.3,4 Other noted constraining factors include, but are not limited to, insufficient time with patients, lack of follow-up, partner or family members in the room, and fear of discussing IPV with patients.5 Of note, associations between healthcare professionals’ demographics and their performance regarding domestic violence appear to be limited to age, professional experience, and economic status.6

Increasingly, medical schools have employed different strategies in an attempt to increase confidence in recognizing and treating IPV and HT. Numerous educational models have been tested including in-person training, online learning modules, and standardized patient interactions. Results overwhelmingly show that, after training, healthcare workers increase their diagnostic confidence and abilities regardless of the educational modality.7,8,9,10,11,12

To facilitate nationwide education on HT, many organizations have created educational materials for implementation in multiple settings. The Department of Health and Human Services, for example, developed “Stop Observe Ask Respond,” or S0AR, in 2013 specifically for use in healthcare settings.

Methods and Materials

This was a prospective quasi-experimental study consisting of all residents of the Creighton University School of Medicine (Phoenix) EM program for the July 2021-June 2022 academic year.

Residents received four lectures on the signs, symptoms, and epidemiology of IPV and HT, as well as the importance of addressing IPV and HT in the ED. Lecture topics included general background on IPV and HT; information on identifying potential victims of IPV or HT; red flags of patient encounters; prevalence in Maricopa County, AZ; tips on working with these patient populations; information on the Sexual Assault Nurse Exam (SANE); and available resources in Maricopa County. These lectures occurred during regularly scheduled protected conference time. They consisted of slide-deck presentations with open discussion, ranging from 15-minute to 1-hour sessions. The curriculum addressed identifying and appropriately counseling patients who may be victims of IPV or HT, as well as reviewing appropriate resources for these patients.

Residents took an identical pre- and post-intervention survey before and after receiving the curriculum to assess if it improved resident knowledge of IPV and HT. Our survey was developed using a similar survey by Short et. al. in their paper titled, “A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence.”13 Additional questions were created to assess for HT knowledge. The survey consisted of 17 questions with Likert scales.

Results

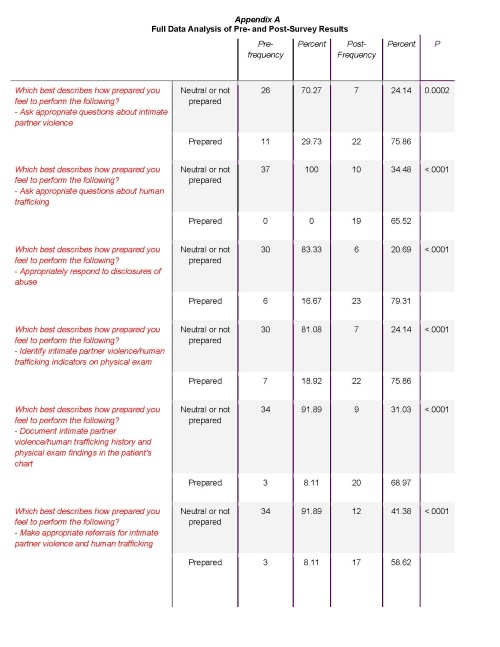

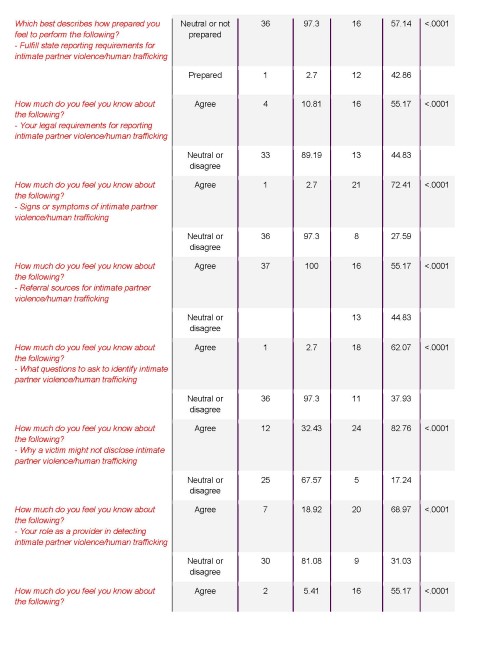

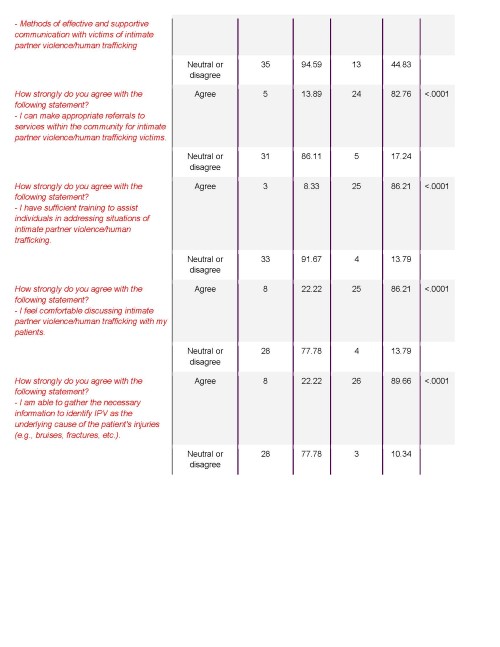

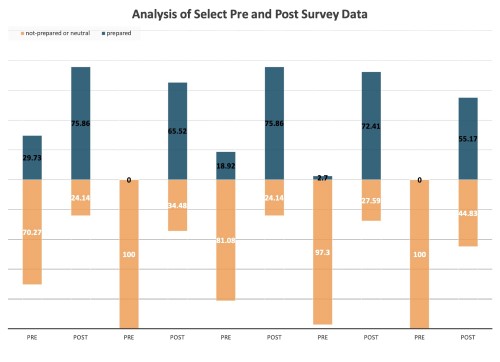

There were 37 responses to the pre-survey and 32 responses to the post-survey. An unmatched chi-squared test was done on all 17 questions. It showed a significant difference in the pre- and post-testing knowledge transfer for all questions with a P value of 0.0002 or less for all questions. (See Appendix A and Figure 1 for full data analysis.)

Figure 1

Discussion

At the time of this writing, training on IPV recognition is not a curriculum requirement for graduation from EM residencies in the United States, even though many victims come through ED doors every day across the country. 3,5,4

The importance of recognizing these victims, and the large potential margin for impact, cannot be emphasized enough.

Our data is limited to one residency program, and strict generalizability to all residency programs is neither appropriate nor our goal in this writing. However, the unfamiliarity with the nuances of recognizing and treating these patients is not unique to this one residency program.4,5

Our study highlights a method of education that was proven to be effective with our cohort. The takeaway from this is twofold: (1) We were able to improve literacy in IPV and HT with our own cohort in a comprehensive fashion using what we consider a reasonable amount of resources and time, with measurable outcome; (2) We recognize a huge need to continue with, and contribute to, the discussion of improving medical education so emergency physicians can properly care for these marginalized groups.

Our methods can be taken as an example. We want to inspire other training programs to find innovative ways to adjust, add on, or revamp modes of education, seeing that our methods worked. (Limitations of this study and its results include variability in resident attendance over the lecture series. Additionally, not all residents provided responses, and the data was not paired, therefore making our pool of data smaller than anticipated.)

Multiple studies within emergency medicine4,5,7,8,9,14 as well as other specialties12 have addressed this issue. Innovative methods included simulation,10 online learning modules,7,8 hired multidisciplinary teams,9 and checklist utilization,1 among others. We applaud these efforts and strive to join these leaders to improve our care of IPV and HT victims.

We plan to continue our education series, with existing and updated curriculum, as new residents join our team. While these efforts cannot be measured and published in this pre- and post-hoc analysis, it is reasonable to assume that these efforts will contribute meaningfully to diversify and continue resident education on IPV and HT. This also opens up potential interventions that may also be studied among our cohort in the future.

As a team of educators and researchers, we hope to have equipped readers with tools for respective cohorts around the world. While it is disparaging to hear how vast and seemingly uncontrolled IPV and HT are, it is reassuring to see efforts made to address them, with measurable improvements. Ultimately, as bedside care providers, we are some of our patients’ most impactful advocates, and we should take pride in that position. As the old adage says, with great power comes great responsibility. As a reader of this article, you already have taken upon that responsibility and shown that initiative. We look forward to reading or hearing of other innovative ways emergency physicians are addressing this problem that has plagued our communities for far too long.

Special thanks to Rana Akkad, MD, Saumya Singh, MD, Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, MSW, PhD, Stefanie R. Ellison, MD, and Dionna White, MSW, LMSW, for their dedication to these patient populations and for helping make this project possible.

References

- Choo EK, Houry DE. Managing intimate partner violence in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(4):447-451.e1.

- How Human Trafficking Happens. Polaris. Updated 2022. Accessed Sept. 25, 2020.

- Toney-Butler TJ, Mittel O. Human Trafficking. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-.

- Dols JD, Beckmann-Mendez D, McDow J, Walker K, Moon MD. Human Trafficking Victim Identification, Assessment, and Intervention Strategies in South Texas Emergency Departments. J Emerg Nurs. 2019;45(6):622-633.

- Hachey LM, Phillippi JC. Identification and Management of Human Trafficking Victims in the Emergency Department. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2017;39(1):31-51.

- Yousefnia N, Nekuei N, Farajzadegan Z. The relationship between healthcare providers' performance regarding women experiencing domestic violence and their demographic characteristics and attitude towards their management. J Inj Violence Res. 2018;10(2):113-118.

- Ma K, Ali J, Deutscher J, et al. Preparing residents to deal with human trafficking. Clin Teach. 2020;17(6):674-679.

- Donahue S, Schwien M, LaVallee D. Educating emergency department staff on the identification and treatment of human trafficking victims. J Emerg Nurs. 2019;45(1):16-23.

- Egyud A, Stephens K, Swanson-Bierman B, DiCuccio M, Whiteman K. Implementation of human trafficking education and treatment algorithm in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2017;43(6):526-531.

- Stoklosa H, Lyman M, Bohnert C, Mittel O. Medical education and human trafficking: using simulation. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1412746.

- Choo EK, Nicolaidis C, Newgard CD, et al. Association between emergency department resources and diagnosis of intimate partner violence. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):83-88.

- Davis JW, Kaups KL, Campbell SD, Parks SN. Domestic violence and the trauma surgeon: results of a study on knowledge and education. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(4):347-353.

- Short LM, Alpert E, Harris JM Jr, Surprenant ZJ. A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):173-180.

- Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements: Version 2.0. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015.