A 70-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department with generalized weakness, decreased oral intake, and diarrhea for 3 days.

He had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery in 2012.

On arrival, the patient was ill-appearing and diaphoretic. Initial vital signs were significant for blood pressure of 82/49, pulse rate of 86 beats/min, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air.

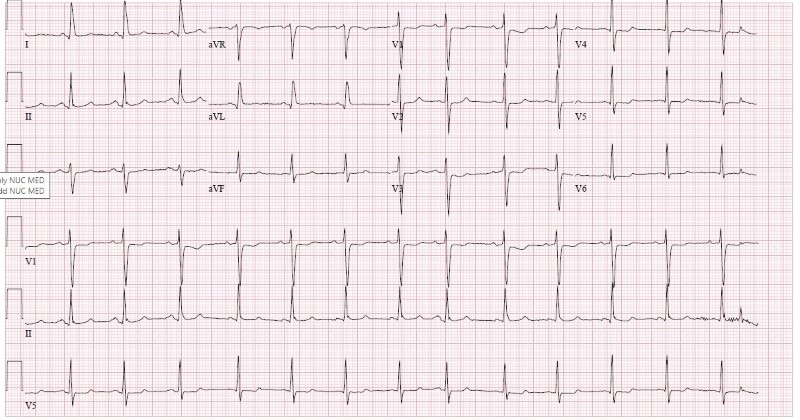

An ECG was obtained on arrival (Figure 1). The patient recently had been admitted and treated for left lower extremity cellulitis and osteomyelitis. The patient’s presentation to the emergency department prompted a sepsis workup.

Figure 1. ECG upon arrival

Clinical Course

The patient presented concerning for sepsis because of his recent hospital admission for cellulitis/osteomyelitis, age >65 years, and hypotension. His pulse rate of 86 was within normal limits but potentially blunted by beta blockade.

Initial lab workup was notable for leukocytosis of 14.41, creatinine 1.8, lactic acid of 3, and troponin of 0.153. Of note, potassium and magnesium were within normal limits.

Vancomycin and cefepime were empirically given for sepsis.

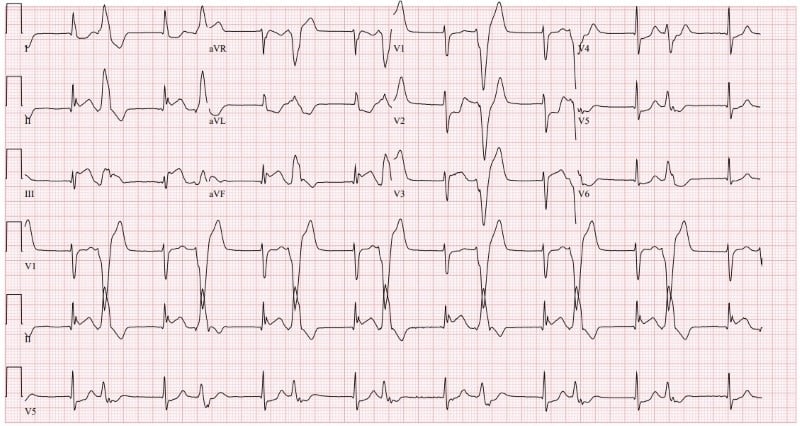

Shortly afterward, the patient developed sudden onset dyspnea, which prompted discontinuation of the antibiotics over concern of possible anaphylactic reaction. The patient continued to endorse dyspnea without skin rashes, wheezing, or stridor; therefore, an additional ECG was performed (90 minutes after the initial ECG) during re-evaluation.

The patient was then found to have acute ST elevation suggestive of STEMI (Figure 2); therefore, an institutional Code STEMI was called.

Figure 2. Repeat ECG in the emergency department

Figure 2. Repeat ECG in the emergency department

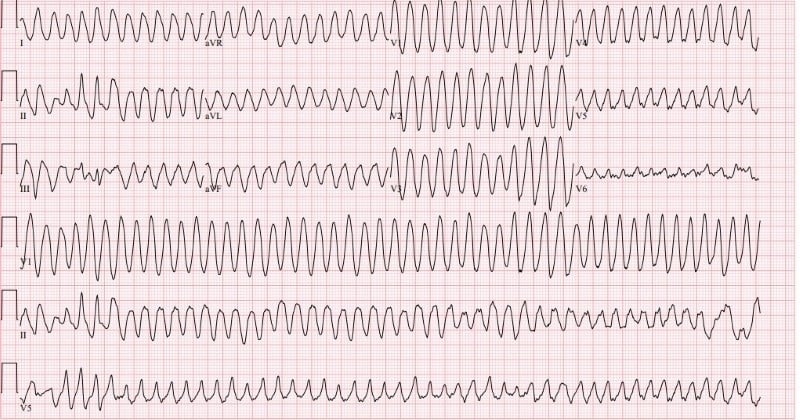

Four minutes later, a third ECG (Figure 3) was performed by staff because the patient became unresponsive. This third ECG showed ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 3. Third ECG, after patient became unresponsive

Manual CPR was initiated, while the patient received bag mask ventilation. Defibrillation was performed within the first few minutes of initiating Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), restoring normal sinus rhythm.

Subsequently, the patient was intubated and transported to a nearby facility with catheterization laboratory capabilities for PCI. The patient was given heparin, ticagrelor, aspirin, and amiodarone. He underwent left heart catheterization, which showed 90% occlusion of LAD and 99% occlusion of the right coronary artery (RCA). The left ventricular ejection fraction was noted to be 50%. PCI with an everolimus-eluting stent system was performed on both vessels with successful revascularization.

The patient did well post-op. He was extubated the following day and discharged home 3 days later.

Diagnosis

The initial ECG (Figure 1) showed normal sinus rhythm at 81 bpm with ST depression in V1 and V2 and nonspecific T-wave changes in V5 and V6. A comparison ECG performed 8 months prior was notable for meeting voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy and bradycardia, but was otherwise within normal limits.

The second ECG (Figure 2) was consistent with inferior ST elevation myocardial infarction noted for ST elevation in leads II, III, and aVF with reciprocal changes in leads I and aVR. This ECG was also notable for multiple PVCs and an accelerated junctional rhythm with hidden P waves at a rate of 94 bpm.

The third and final ECG (Figure 3) showed wide complex tachycardia at 265 bpm consistent with ventricular tachycardia.

Discussion

Identifying a rapidly evolving myocardial infarction in the ED in a patient with a distracting presentation necessitates a timely diagnosis and prompt provider evaluation. As discussed previously, this patient presented with clinical and laboratory findings consistent with sepsis. On initial presentation, there were no typical symptoms of myocardial ischemia such as chest pain or shortness of breath.1

However, the patient was noted to be diaphoretic. Atypical presentation of chest pain — such as gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting, which are commonly associated with elderly females or diabetic patients — was not evident.2

Although the patient did have an elevated HEART score of 5 on presentation, the use of this risk stratification device may not be applicable in this case because of the absence of chest pain or suspicion of ACS on presentation.

The initial ECG showed normal sinus rhythm and mild elevation in troponin (0.153). Troponin was initially thought to be elevated due to myocardial injury in relation to sepsis, which is seen in 85% of adults with sepsis.3

Approximately 1 hour after arrival, the patient began experiencing sudden onset dyspnea, which initially was thought to be associated with the administration of antibiotics. ST elevation changes in the setting of anaphylaxis were reported to be seen in Kounis syndrome, which is thought to be due to the release of histamine following mast cell activation leading to coronary artery vasospasm, plaque erosion, or even rupture.4

However, in the absence of cutaneous (blanching rashes) or respiratory findings (i.e., wheezing/stridor) on physical exam, anaphylaxis was unlikely in this case. Recognition of the patient’s change in status and symptoms prompted a rapid re-evaluation, leading to identification of evolving myocardial ischemia.

Take-Home Points

- Always be prepared for a change in patient status. When these situations arise, quickly and thoroughly re-evaluate the patient with a new and broader differential diagnosis.

- Keep atypical presentation of myocardial infarction as a differential diagnosis, especially in patients with advanced age and with risk factors for atypical presentation such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.2

- Rates of in-hospital cardiac arrest are 9-10 per 1,000 hospital admissions, and the survival rate is approximately 20%. Prompt re-examination and evaluation of the patient, as well as efficient transition to ACLS when identified, is of the utmost importance.5

- In the setting of cardiac arrest, time from onset of ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia to defibrillation is crucial. According to the American Heart Association, defibrillation in fewer than 2 minutes of recognition of a shockable rhythm has been associated with greater rates of long-term survival at 1-5 years.6

References

- Lu L, Liu M, Sun R, Zheng Y, Zhang P. Myocardial Infarction: Symptoms and Treatments. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;72(3):865-7.

- Khan IA, Karim HMR, Panda CK, Ahmed G, Nayak S. Atypical Presentations of Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35492.

- Garcia MA, Rucci JM, Thai KK. Association between Troponin I Levels during Sepsis and Postsepsis Cardiovascular Complications. ATS Journals. 2021; 204(5).

- Memon S, Chhabra L, Masrur S, Parker MW. Allergic acute coronary syndrome (Kounis syndrome). Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015;28(3):358-62.

- Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Review. JAMA. 2019;321(12):1200-1210.

- Patel, KS, Spertus, JA, et al. Association Between Prompt Defibrillation and Epinephrine Treatment With Long-Term Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circulation. 2017; 26(137): 2041-51.