Clinical case

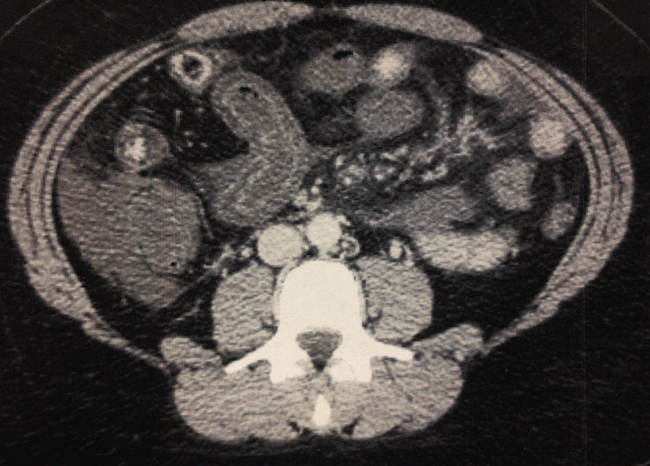

A 31-year-old female presents with severe intermittent epigastric abdominal pain. She reports that this pain began 3 weeks ago and has slowly increased to 10/10 in severity. For the past two days, she had nausea and non-bloody, non-bilious vomiting. Her history includes anxiety, depression, and gastritis. A recent endoscopy performed by her gastroenterologist showed evidence of gastritis, and she is taking lansoprazole daily without relief. She is noted to be slightly tachycardic at 103 bpm, and has mild epigastric tenderness. Initial blood work is within normal limits. After one GI cocktail and multiple rounds of dilaudid did not ease her pain, a contrasted CT scan was performed. This showed acute mesenteric ischemia secondary to extensive thrombus formation in the portal, superior mesenteric, and splenic veins (Figure 1). She is admitted to the surgical intensive care unit, where further laboratory studies reveal a protein S level of less than 10%, and a diagnosis of protein S deficiency is made.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of the abdomen shows superior mesenteric vein occlusion, extended from the portal vein.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of the abdomen shows superior mesenteric vein occlusion, extended from the portal vein. Figure 2. Computed tomography imaging of the abdomen shows thickening of the bowel indicating ischemia, with stranding and fluid in the mesentery.

Figure 2. Computed tomography imaging of the abdomen shows thickening of the bowel indicating ischemia, with stranding and fluid in the mesentery.Introduction

Gastritis is a common diagnosis in the ED and can have many presentations, including colicky epigastric pain. While much less common, portomesenteric venous thrombosis often presents with similar symptoms. This is a diagnosis that should not be missed, since it requires very different therapy and the acute outcomes are much worse. A comprehension of abdominal venous anatomy is key to understanding the danger of the disease. Because the portal vein is formed by the confluence of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins, thrombosis can extend into these venous pathways, and, in turn, can cause acute ischemia. The potential for misdiagnosing a patient with these clinical presentations is high, which creates a huge risk for the patient. We can greatly improve clinical outcomes if we're attentive to the clinical situation, and more willing to consider a broader differential.

The diagnosis of portomesenteric venous thrombosis is based on high clinical suspicion, since it can so easily masquerade as other more benign conditions.

Discussion

Acute mesenteric ischemia can have multiple causes. Approximately 95% of cases are due to arterial occlusion, which can be secondary to thrombotic or embolic events.1 The remaining 5% is due mostly to venous occlusion, specifically portomesenteric venous thrombosis.1

The etiology of portomesenteric venous thrombosis can be best categorized into 3 types: local, inherited, and acquired. Local risk factors cause inflammation in the abdomen, such as pancreatitis, diverticulitis, appendicitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.2 These are typically more apparent with an underlying thrombophilia.1 Inherited risk factors include thrombophilias, such as factor V leiden and protein S and C deficiencies. The incidence of venous thrombosis is 0.5 to 1.65% per year in patients with protein S deficiency.3 There are a multitude of acquired risk factors which can cause thrombosis, the most common being liver cirrhosis. Other major acquired factors include abdominal surgery, immobilization, pregnancy, and the use of oral contraceptives.

The diagnosis of portomesenteric venous thrombosis is based on high clinical suspicion, since it can so easily masquerade as other more benign conditions. Taking a thorough history is very important. Specifically, a past medical or family history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism is present in about 50% of patients with portomesenteric venous thrombosis.4 Clinically, these patients can present in a variety of ways, depending on the extent of venous obstruction and rate of thrombus development.

Patients with acute portal vein thrombosis can sometimes have silent presentations, with their thrombosis incidentally discovered on CT scan for other reasons. In these cases, there can often be some diagnostic uncertainty. Sometimes a repeat contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen can help differentiate the thrombus from the vessel wall.5 Otherwise, these patients are typically symptomatic, and usually present with fever, dyspepsia, or abdominal pain, which can be either sudden, or progressive over weeks.2 When the thrombus extends to the superior mesenteric vein, the abdominal pain is often reported to be “colicky,” and associated with diarrhea.2 If there is further expansion into the mesenteric venous arches, ischemia can occur, and will lead to bowel infarction. CT may reveal thickening of the intestinal wall, lack of mucosal enhancement, or intramural gas. These findings all are suggestive of bowel infarction, which may lead to severe sepsis and sometimes septic shock (Figure 2).2 A CT scan is the diagnostic test of choice for suspected cases of portomesenteric venous thrombosis.

Physical findings appear to be less useful for making a diagnosis. They do not explain mesenteric ischemia of arterial or venous origin very well.6 There may be some distension of the abdomen or perhaps guarding, but no one physical exam finding correlates well with a diagnosis of portomesenteric venous thrombosis.6

Laboratory testing may be a little more helpful. Tests may show elevated levels of acute phase reactants, including c-reactive protein, serum amyloid A, and complement factors. Lactates may be normal in the early stages of thrombosis, but can be very helpful if the level is high, and may indicate bowel ischemia. Liver function tests are typically normal, since hepatic arterial blood flow can compensate for the decreased portal inflow. Patients with bowel infarction may have signs of metabolic acidosis, leukocytosis, or hemoconcentration that can lead to an elevated hematocrit.

Therapy

The primary therapy for acute portomesenteric thrombosis is anticoagulation, which prevents extension of the thrombus and ideally prevents infarction of the bowel. Initially, unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin can be used to quickly achieve therapeutic anticoagulation levels. Therapeutic unfractionated heparin may be prefered, since it only needs to be stopped four hours prior to surgery, compared with low molecular weight heparin, which is usually held 24 hours prior to operative interventions.3 Heparin treatment can be resumed 24 hours after the procedure.

Once stabilized, treatment can shift to oral anticoagulation, and should be continued for 6 to 12 months.6 Lifelong anticoagulation is suggested if prothrombic risk factors are present. In one study, a high rate of recanalization of the portomesenteric veins was achieved in 25 out of 31 patients (80.6%) when anticoagulation was started at time of presentation.7 If the patient develops transmural necrosis or bowel perforation, urgent surgical intervention will be needed. For patients with thrombophilia undergoing surgical interventions for venous thrombosis, the perioperative risk of new thromboembolic events is very high; management of these patients should involve the surgical team, and a clear discussion should be had with the patient.

Conclusion

The differential diagnosis of the patient in this scenario was potentially quite broad. However, her history of gastritis being treated with a PPI, a common presentation, and recent endoscopy make it easy to anchor to the wrong conclusion. But, instead of a relatively benign “stomach upset,” this patient had a potentially lethal underlying disease process ”” protein S deficiency with thrombosis. If the diagnosis had been missed, her outcome easily could have been much different. Luckily for her, she did not require any operative management, and conservative therapeutic heparin was successful. Taking a minute to think twice before diagnosing a patient with common gastritis may yield surprising live-saving results.

References