Pyruvate + NADH + H+ †” lactate + NAD+

Lactic acidosis is a commonly encountered phenomenon within the emergency department (ED). In the setting of sepsis, elevated lactate levels can be an indicator of hypoxia or decreased perfusion. Its clearance can be a sign of increased perfusion. However, lactic acidosis is much more encompassing and can be the result of many other pathophysiologic processes.

Broadly, lactic acid can be broken down into two isomers—D- and L- lactate. It is L-lactate that is further sub-typed into 2 categories—hypoxic (Type A) and non-hypoxic (Type B).1 Hypoxic causes of lactic acidosis include ischemia, shock, cardiac arrest, carbon monoxide poisoning, respiratory failure, and regional hypoperfusion. Some non-hypoxemic causes include renal or hepatic dysfunction, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, seizures, diabetic ketoacidosis and many drug toxicities.

One uncommonly recognized cause of lactic acidosis is albuterol-induced lactic acidosis. When treating asthmatic patients, lactic acidosis creates a unique situation whereby patients may appear more dyspneic despite improvement in bronchospasm. This is the result of a compensatory respiratory mechanism for their metabolic acidosis. Unfortunately, physicians may believe their patient is not improving and administer more albuterol, leading to a vicious cycle that results in worsening respiratory status or respiratory failure.

Pathophysiology

The normal blood lactate concentration in patients is 0.5-1mmol/L. Hyperlactatemia is defined as an elevated lactate concentration (2-4mmol/L) without metabolic acidosis.2 It occurs when lactate production exceeds lactate consumption. Lactic acidosis, on the other hand, is defined as increased blood lactate levels (usually greater than 5mmol/L) leading to a metabolic acidosis. Lactate is a byproduct of glycolysis, and its formation increases when the rate of pyruvate formation in the cytosol exceeds its rate of use by the mitochondria. This occurs with rapid rises in metabolic rates or when oxygen delivery to the mitochondria declines, which occurs in tissue hypoxia.

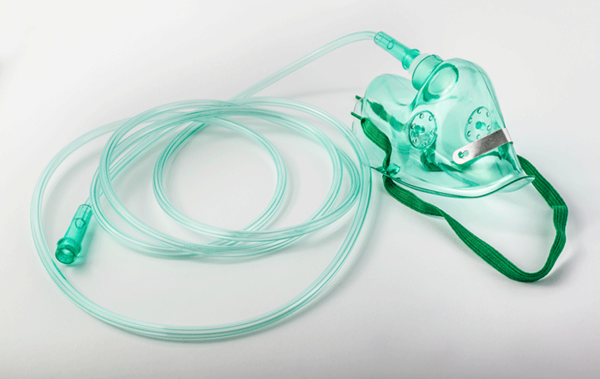

Albuterol is a β2-adrenergic agonist, which is a potent bronchodilator. The mechanism of action by which albuterol acts is by increasing cAMP and therefore causing smooth muscle relaxation.3 The exact mechanism of action by which albuterol causes lactic acidosis is not completely known, but a dose of 1mg/kg appears to be the threshold for developing clinically significant toxicity.4 It is thought that albuterol creates a hyperadrenergic state. High levels of these catecholamines can aggravate hyperlactatemia by reducing tissue perfusion and overstimulating the β2 adrenoceptor.5 This, in turn, enhances glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis and subsequently increases glycolysis and pyruvate production. However, pyruvate cannot enter the Krebs cycle because of concurrent increases in lipolysis and increased free fatty acid production, which inhibits the pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme. This shifts pyruvate to be reduced to lactate.6,7 (See formula below)

Clinical Practice

Patients with asthma or wheezing are usually initially treated with albuterol. When a patient has had too much albuterol and a subsequent increase in lactic acid, it creates a paradoxical picture. As mentioned above, while the bronchospasm may improve, patients may appear more dyspneic or tachypneic.1

With the increased respiratory rate, patients are physiologically compensating for the metabolic acidosis that is occurring. Health care providers may interpret these signs and symptoms as worsening asthma and therefore give more albuterol.7

However, this propagates the cycle of worsening respiratory effort and can ultimately lead to respiratory failure. The best way to identify and avoid this situation is by keen situational awareness, attentive physical exams, and serial peak flow measurements. Physicians should complete multiple, thorough lung exams to assess for improvement or resolution of wheezing and recognize when to stop repeated doses of albuterol.

Future

Albuterol is a very commonly used medication, especially in the ED. The best way to prevent albuterol-induced lactic acidosis is to recognize its potential to occur and assess patients accordingly. Further research is needed to decipher if what doses or combinations of medications used in asthma can be as efficacious without the potential deleterious side effect of lactic acidosis.

References

- Dodda VR, PS. Can Albuterol Be Blamed for Lactic Acidosis? Respiratory Care. 2012;57(12):2115-2118.

- Gunnerson KJ. Lactic Acidosis. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/167027-overview.

- Flomenbaum N, Goldfrank L, Hoffman R, Howland M, Lewin N, Nelson L. Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. 2006.

- Liem EB, Mnookin SC, Mahla ME. Albuterol-induced Lactic Acidosis. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:505-506.

- Lemanske RF. Beta agonists in asthma: Acute administration and prophylactic use. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/beta-agonists-in-asthma-acute-administration-and-prophylactic-use.

- Kraut JA, Madias NE. Lactic Acidosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2309-2319.

- Assadi FK. Therapy of Acute Bronchospasm. Clin Pediatr. 1989;28(6):258-260.