Case Presentation

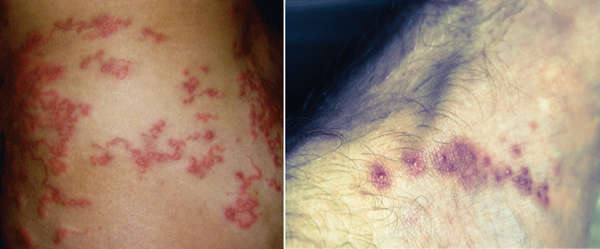

You step into the room of a 22-year-old female sent from her primary care physician for incision and drainage of two facial abscesses. She has had swelling, redness, and discharge from her forehead and right infra-orbital region that began a few weeks ago. She lives in New York but returned from the Amazon two months ago, where she suffered multiple insect bites. On her exam she has two erythematous, indurated nodules with seropurulent discharge in the regions mentioned (Image 1). Upon closer inspection, the tip of a white larva can be seen migrating in and out of a punctum in the infra-orbital nodule. It becomes clear this is no longer a case of an ordinary abscess”¦

Introduction

Skin disorders affect 12-18% of all travelers and are among the six most common reasons returning travelers seek medical care.1, 2 The differential diagnosis for skin lesions in the returning traveler is broad and is based on the appearance of the skin lesion, travel locations and duration, and associated symptoms. Dermatoses seen in travelers can be broadly grouped into infectious and non-infectious etiologies. Skin infections are a result of bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, helminths, and protozoa. Non-infectious dermatoses are secondary to arthropod bites, allergic reactions, trauma, sunburn, and animal bites.3

The 10 most frequently encountered dermatologic diagnoses in travelers are listed in Table 1.4 Other significant infections include rickettsia, dengue, swimmer's itch, filariasis, leprosy, seabather's eruption, and mycobacterium marinum. Emergency physicians should be familiar with all of these entities, but we will focus on the four most common tropical infections: cutaneous larva migrans, leishmaniasis, tungiasis, and myiasis.

Cutaneous Larva Migrans (CLM)1,4-7

Epidemiology: CLM is the most common dermatologic infectious disease in the returning traveler. It is caused by the hookworm larva, most commonly by the cat and dog hookworms, Ancyclostoma braziliense and caninum, respectively. The larva is found in soil and sand and is acquired by walking barefoot in endemic areas. CLM is found in Southeast Asia, Africa, South America, the southern United States and the Caribbean. CLM is the diagnosis in approximately 10% of travelers returning with skin complaints.

Incubation/latency: Symptoms can begin as early as a few hours after exposure and as late as one month after exposure.

Presentation: Patients present with a serpiginous and migrating rash associated with intense pruritis. Vesiculobullous lesions may also be seen in 10-15% of cases. Feet are most frequently affected, followed by the buttocks and thighs. At any given time, 1 to 3 lesions may be present.

Diagnosis: The diagnosis is made clinically upon CLM's characteristic appearance and the patient's travel history.

Treatment: Ivermectin 0.2mg/kg PO, repeated once or twice, or albendazole 400mg PO as single dose, or for three days.

Prognosis: Spontaneous resolution occurs after several weeks (usually 2-8 weeks), however, a single dose of ivermectin is associated with a 94-100% cure rate and significantly reduces duration of symptoms.

Prevention: Wearing shoes.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL)1,4,5,8-10

Epidemiology: Leishmaniasis is caused by a heterogeneous group of intracellular protozoa belonging to the genus Leishmania. It is transmitted by the female sand fly and is found in Mexico, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Southern Europe. The majority of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases are seen in Afghanistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and Peru. CL accounts for approximately 3% of skin disease in returning travelers. Males, immunocompromised hosts, and travelers visiting endemic areas for more than two months are at increased risk of acquiring CL.

Incubation: The incubation period is typically a few days to months, with an average incubation period of 9 weeks.

Presentation: The main clinical form of CL is localized CL. Localized CL begins as an erythematous papule at the site of the bite, and enlarges to a nodular plaque with subsequent ulceration. The lesion is typically found on exposed skin and is usually painless. Satellite lesions, nodular lymphangitis, and lymphadenopathy may be present. Most patients will present with 1 to 3 lesions, but rarely will exceed 10 eruptions.

Diagnosis: A full thickness punch biopsy is needed for a definitive diagnosis. The diagnosis can be made by smear, histopathology, culture, or PCR.

Treatment: Many lesions will spontaneously resolve; however, treatment should be given to prevent progression to disseminated leishmaniasis. Local therapy is warranted in uncomplicated CL (cryotherapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin, intra-lesional pentavalent antimony), while systemic agents (oral azoles and intravenous amphotericin B, pentamidine, and pentavalent antimonials) should be used in cases of complicated CL. Drug choice is based on species, drug resistance, and geographic location. Expert consultation should be obtained prior to initiation of treatment. Superimposed bacterial infection is common and requires antibiotics.

Prognosis: Cutaneous leishmaniasis is usually self-limiting, but it carries a 3% risk of progression to disseminated leishmaniasis.

Prevention: Repellents, bed nets, and protective clothing.

Tungiasis4,5,11-13

Etiology: Tungiasis is a parasitic skin infection caused by the gravid female sand flea, also known as the jigger flea, Tunga penetrans. The sand flea attaches itself when the host walks with bare feet on sand or soil. Risk factors include poor sanitation and personal hygiene. It is found in tropical and sub-tropical climates in South and Central America, Africa, the West Indies, and the Caribbean. Tungiasis can represent 4-6% of diagnoses in returning travelers. A high prevalence (>50%) of infestation is seen in some endemic areas.

Incubation: 1 to 2 weeks after flea skin penetration.

Presentation: About 99% of lesions occur in feet. The lesion is a papule or nodule with a central black point corresponding to the opening used to lay eggs. Extrusion of eggs and feces may be visible. Pain, swelling, and pruritis typically occur with growth of the flea. The flea usually involutes and dies and is sloughed off with the epidermis after 4-6 weeks.

Diagnosis: Identification of sand flea, morphology of skin lesion, and travel history.

Treatment: There is no known drug treatment. Surgical extraction is the most appropriate treatment. Otherwise, the flea is typically sloughed off with normal skin growth after several weeks. Bacterial super-infection is common and requires antibiotics. Tetanus prophylaxis should be given if not up to date.

Prognosis: Infestation is typically self-limiting in travelers. Inhabitants of endemic areas can develop severe and debilitating disease.

Prevention: Wearing closed-toed shoes and applying bug repellents can decrease the risk of transmission.

Myiasis1,4,5,14-19

Epidemiology: Myiasis is an infestation of human tissue by the larvae of dipterous (two-winged) flies. Its name is derived from the Greek word myia, meaning fly. The two predominant causative pathogens are Dermatobia hominis, the human botfly, which is found in Latin America, and Cordylobia anthropophaga, the tumbu fly, found in Africa.

In Latin America, the human botfly lays eggs on the abdomen of ticks, mosquitoes, or other flies, which then deposit the eggs on animals or humans. In Africa, the tumbu fly lays its eggs directly on linen, clothing, and soil (never on humans or animals), which are then transferred to skin upon contact. Worldwide, myiasis affects 2.7-3.5% of returning travelers with skin disease.

Incubation: The incubation period for D. hominis is 5-12 weeks. The incubation period for C. anthropophaga is much shorter, spanning 8-20 days.

Presentation: Human myiasis is subdivided into furuncular cutaneous myiasis, wound myiasis, migratory cutaneous myiasis, and myiasis of body cavities. Furuncular cutaneous involvement is the most common presentation of myiasis and presents as a nodule or furuncle with a central breathing pore. Serous, serosangenous, and purulent discharge may be expressed from the lesion. Patients may report pain, pruritus, and sensation of movement inside of the lesion. Patients returning from Latin America typically have 1 to 3 lesions that are found on exposed skin, while patients returning from Africa may have multiple lesions that are found on areas covered by clothing.

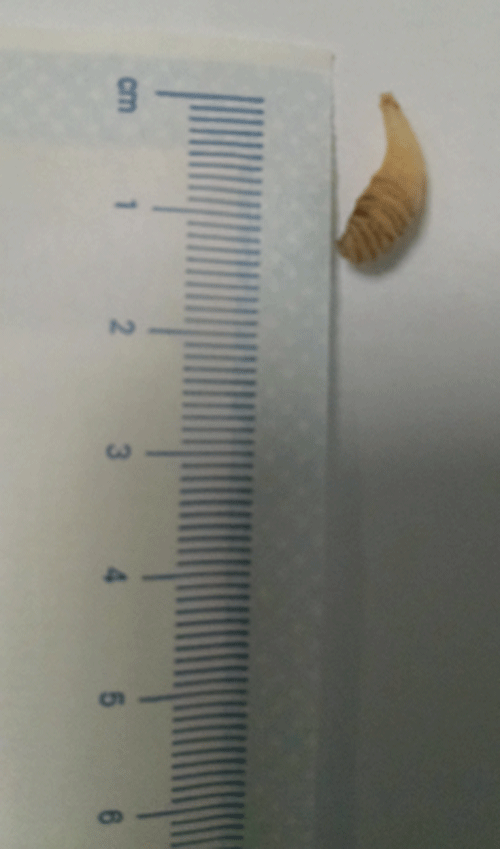

Diagnosis: Identifying the specific larva makes the diagnosis.

Treatment: Extracting larva with forceps or manual pressure. Occluding the central punctum with a sealing ointment (petroleum jelly, bacitracin, paraffin) will facilitate the removal of the larva by causing asphyxiation, forcing the larva to exit the pore for oxygenation. Surgical excision may be required if the larva is unable to be extracted. Secondary bacterial infection is very uncommon because of bacteriostatic substances produced in the gut of the larva, but should be treated if present. Oral ivermectin can be used in cases of extensive disease or failed extraction. The patient's tetanus status should be brought up to date.

Prognosis: Usually self-limiting and benign, though may require surgical treatment.

Prevention: In Latin America, use mosquito repellents and nets. In Africa, avoid drying laundry outside, and iron any clothing that was left to dry outside.

Case Resolution

Initial attempts to remove the larva with forceps are unsuccessful, as the parasite would quickly retract with any nearby movement. Petroleum jelly is applied over the lesion, and after several minutes the larva begins to emerge from the aperture. It is then easily removed with forceps. No larva is visualized within the forehead lesions, so the patient is referred to plastic surgery for debridement. The removed larva is sent to pathology, and the diagnosis of botfly is confirmed.

Table 1. Top 10 Skin Infections Seen in Travelers Abroad4

| 1. | Cutaneous larva migrans |

| 2. | Soft tissue bacterial infections (pyoderma, abscess) |

| 3. | Arthropod bite |

| 4. | Allergic reaction to urticarial |

| 5 | Myiasis |

| 6. | Superficial fungal infection |

| 7. | Injuries (including animal bites) |

| 8. | Scabies |

| 9. | Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

| 10. | Tungiasis |

References

- Lederman ER, Weld LH, Elyazar IR, von Sonnenburg F, et al.GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Dermatologic conditions of the ill returned traveler: an analysis from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Int J Infect Dis 2:593-602, 2008.

- Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, et al.Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Surveillance for travel-related disease--GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997-2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 62:1-23, 2013. - Wilson, ME. Skin lesions in the returning traveler. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA.

- O'Brien BM. A practical approach to common skin problems in returning travellers. Travel Med Infect Disease. 7:125-46, 2009.

- Zimmerman RF, Belanger ES, Pfeiffer CD. Skin infections in returned travelers: an update. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 17:467, 2015.

- Bouchaud O1, Houzé S, Schiemann R, Durand R, et al. Cutaneous larva migrans in travelers: a prospective study, with assessment of therapy with ivermectin. Clin Infect Dis. 31:493-8, 2000.

- Hochedez P1, Caumes E. Common skin infections in travelers: J Travel Med. 15:252, 2008.

- Aronson N. Clinical manifestation and diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA.

- ”œLeishmaniasis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 10 Jan. 2013.

- Savoia D. Recent updates and perspectives on leishmaniasis: J Infect Dev Ctries. 4:588-96, 2015.

- Feldmeier H, Sentongo E, Krantz I. Tungiasis (sand flea disease): a parasitic disease with particular challenges for public health. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 32(1):19-26, 2013.

- Lefebvre M1, Capito C, Durant C, et al. Tungiasis: a poorly documented tropical dermatosis. Med Mal Infect. 41:465-8, 2011.

- Feldmeier H1, Keysers A. Tungiasis - A Janus-faced parasitic skin disease. Travel Med Infect. 14. 11:357-65, 2013.

- Arosemena R, Booth SA, Su WP. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 28:254, 1993.

- Lachish T, Marhoom E, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Myiasis in Travelers. J Travel Med. 22:232-6, 2015.

- Villwock, Jennifer A JA. Head and neck myiasis, cutaneous malignancy, and infection: a case series and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 47:e37-41, 2014.

- Sampson CE, MaGuire J, Eriksson E. Botfly myiasis: case report and brief review. Ann Plast Surg. 46:150”“152, 2001.

- Tsuda S, Nagaji J, Kurose K, et al. Furuncular cutaneous myiasis caused by Dermatobia hominis larvae following travel to Brazil. Int J Dermatol. 35:121-3.

- Jelinek T, Nothdurft H, Rieder N, Loescher T. Cutaneous myiasis: review of 13 cases of travelers returning from tropical countries. Int J Dermatol. 34:624-6, 1995.