A 68-year-old female with a history of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presents to the emergency department (ED) complaining of painless vision loss in her left eye. She reports that over the past week she has been seeing “spots” across her visual field, progressing to complete loss of vision today. Her visual acuity is 20/40 on the right and 20/200 on the left. There is no scleral injection, chemosis, or drainage. She has intact extraocular movements and her pupils react equally to light. Slit lamp exam reveals no foreign body or abrasions; however, it is difficult to assess the retina because of blood in the posterior chamber. You prepare to call your ophthalmology colleagues, but before you do, you pull over the ultrasound to see if you can determine a more precise cause for this patient's symptoms.

Anatomy

Knowledge of eye anatomy is imperative when performing an ocular ultrasound. The structures of interest in this case all lie posterior to the lens in the area called the posterior segment. Together, the vitreous body and the posterior ocular wall form the posterior segment. The posterior ocular wall includes the retina, choroid and sclera. The retina has three insertion points: posteriorly at the optic disc and anteriorly at the medial and lateral aspects of the orbit at the ora serrata (Figure 1).1

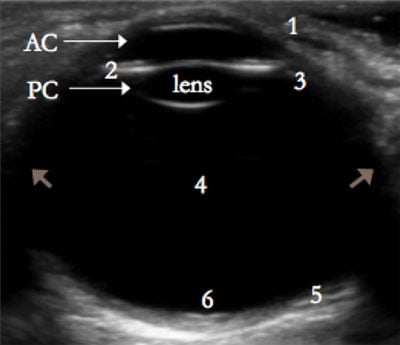

FIGURE 1. Ocular Anatomy

FIGURE 1. Ocular Anatomy

Anterior segment = cornea (1), anterior chamber (AC), iris (2), ciliary body (3), lens, and posterior chamber (PC).

Posterior segment = vitreous chamber (4) and posterior ocular wall (5).

Retina attaches anteriorly at ora serrata (small arrows) and posteriorly at optic disc (6).

Definitions

Vitreous hemorrhage is defined as bleeding into the vitreous body and can be traumatic or non-traumatic. Diabetic retinopathy, retinal detachment, posterior vitreous detachment, retinal macroaneurysms, and macular degeneration comprise some of the non-traumatic causes of vitreous hemorrhage. The majority of non-traumatic cases are managed conservatively with follow-up imaging at 2-4 week intervals to monitor for clearing. If the hemorrhage is secondary to trauma or retinal detachment, management of the traumatic injury or the retinal detachment is necessary.1

Posterior vitreous detachment occurs when the posterior vitreous capsule detaches from the retina. This is usually an age-related phenomenon that does not require emergent intervention but may lead to retinal detachment in the future. Patients should follow closely with ophthalmology.1

Retinal detachment occurs when the inner neuronal layer of the retina separates from the outer pigmented layer. Small segments of the pigmented layer may break off, creating what patients often describe as “floaters” in the visual field. Causes of retinal detachment range from trauma to connective tissue disorders to simple aging. All retinal detachments require emergent ophthalmologic consult.1

Differentiating between the three conditions often presents a diagnostic quandary because all three may have similar presenting symptoms. Bedside ultrasound is an ideal diagnostic tool to help differentiate between these three pathologies.

Figure 2. Model of Ocular Ultrasound

Figure 2. Model of Ocular Ultrasound

(Left: Gel placement; Middle: Transverse Axis; Right: Longitutinal Axis)

Technique

Ocular ultrasound is a useful when patients present with an acute visual abnormality. The linear high-frequency probe (7.5-15.0 MHz) provides optimal resolution. Choose the “superficial” or “small parts” preset and adjust the depth to optimize visualization of the globe. Gain should be turned down to interrogate the anechoic vitreous humor, after which the gain should be slowly increased to identify subtle abnormalities without creating false artifacts.2

Hold the probe with the thumb and index finger and rest the remainder of the hand on the bony structures of the face to maintain a stable view.3 Placement of a protective film (such as transparent dressings) over the closed eye with a generous layer of gel allows for better visualization of structures without needing to apply pressure onto the orbit.4 Pan through the globe in both

the transverse and longitudinal axes (Figure 2).

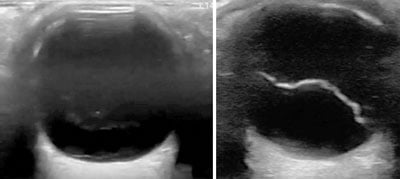

Figure 3. Vitreous Hemorrhage (left). (Note “swaying” fibers with no attachment to optic disc) Figure 4. Vitreous Detachment (right)

Figure 3. Vitreous Hemorrhage (left). (Note “swaying” fibers with no attachment to optic disc) Figure 4. Vitreous Detachment (right)

Figure 5. Retinal Detachment

Figure 5. Retinal Detachment(Note the fine fiber attached to the optic disc)

Ultrasound Findings

Early vitreous hemorrhage appears as low-amplitude hyperechoic areas, which may require an increase in gain to fully appreciate. As the blood matures it forms mobile membranes, which can be differentiated from retinal detachment by their fine structure, their lack of attachment to the optic disc, and anterior to posterior orientation.1,3 When the patient moves the eye, these membranes move like “swaying seaweed” (Figure 3).

Posterior vitreous detachment is seen as a freely mobile hyperechoic membrane that swirls away from the optic disc with movement of the eye. This finding differs from a retinal detachment in that it “crosses the midline,” with the optic disc representing the midline (Figure 4).1

It may be challenging to differentiate a retinal from vitreous detachment depending on the angle of visualization. The retina will always remain attached at the optic disc because the retina is continuous with the optic sheath, whereas the vitreous body is not. In a partial detachment, the operator will see a “V” shape in the posterior segment, representing the retina attached to the optic disc posteriorly and the ora serrata anteriorly. Notably, to differentiate between a retinal and a vitreous detachment, the optic nerve must be visualized. The retina may or may not remain attached to its anterior attachment site at the ora serrata. (Figure 5).1,3

Table 1. Comparison of Posterior Eye Pathologies

| Pathology | Mechanism | Ultrasound Findings | Management |

| Vitreous Hemorrhage | Bleeding into vitreous body | Anterior-posterior, swaying seaweed | Repeat ultrasound in 2-4 weeks, dx underlying cause |

| Posterior Vitreous Detachment | Separation of vitreous capsule from retina | Crosses optic disc “midline” | Ophthalmology follow-up |

| Retinal Detachment | Separation of inner sensory layer from outer pigmented layer | Attachment to optic disc, V shape | Emergent ophthalmology evaluation and possible intervention |

Evidence

Point-of-care beside ocular ultrasound has demonstrated high sensitivity (97-100%) and specificity (83-97%) for detection of retinal detachment.5-7 However, there is minimal evidence in the literature using bedside ultrasound to diagnose posterior vitreous detachment or vitreous hemorrhage. One retrospective study of 130 pre-operative ocular ultrasounds performed by a single operator reported 92.3% sensitivity and 98.3% specificity for identifying retinal detachment, 96.2% and 100% for posterior vitreous detachment, and 100% and 100% for vitreous hemorrhage.8 The study has limitations, but results suggest that with proper training, ultrasound can be both sensitive and specific for identifying ocular pathology.

Bottom Line

Bedside ocular ultrasound is useful in identifying pathology in the posterior segment. Three closely related conditions include vitreous hemorrhage, posterior vitreous detachment and retinal detachment (Table 1). Correct identification is important given the different management strategies. Studies support accurate diagnosis of retinal detachment in the ED. Further research and training to accurately identify additional pathology is needed.

References

- De La Hoz PM, Torramilans LA, Pozuelo SO, Anguera BA, Esmerado AC, Caminal Mitjana JM. Ocular ultrasonography focused on the posterior eye segment: what radiologists should know. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(3):351-364.

- Tham E. Ocular Ultrasound. In: Carmody KA, Moore CL, Feller-Kopman D, eds. Handbook of Critical Care & Emergency Ultrasound. 2011, McGraw Hill Medical: New York; 2011:185-192.

- Kilker BA, Holst JM, Hoffmann B. Bedside ocular ultrasound in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):246-253.

- Roque PJ, Hatch N, Barr L, Wu TS. Bedside Ocular Ultrasound. Crit Care Clin. 2014;30(2):227-241.

- Bavias M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski P. A study of bedside ocular ultrasonopgraphy in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(8):791-799.

- Shinar Z, Chan L, Orlinsky M. Use of ocular ultrasound for the evaluation of retinal detachment. J Emerg Med. 2011 Jan;40(1):53-57.

- Yoonessi R, Hussain A, Jang TB. Bedside ocular ultrasound for the detection of retinal detachment in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Sep;17(9):913-917.

- Parchard S, Singh R, Bhalekar. Reliability of Ocular Ultrasonography Findings for Pre-surgical Evaluation in Various Vitreo-retinal Disorders. Semin Ophthalmol. 2014;29(4):236-241.