Post-pandemic vacations are picking up steam - and outdoor getaways remain popular. Are you ready to handle bites, stings, and other envenomations?

Rattlesnake

A 50-year-old female is celebrating Labor Day weekend with you and your friends in New Mexico. She is swimming at a lake, and upon walking out of the water feels a sharp pain around her ankle. You notice a snake under a rock near her foot and take a photo with your phone as shown. You see 2 small dots around her ankle, and you’re 3 miles from your car and another 1-hour drive from the nearest hospital. She is neurovascularly intact with a normal exam except for subjective pain.

This woman has sustained a bite from a rattlesnake and possible envenomation. Rattlesnakes are classified as crotalinae, also known as pit vipers.1 The name pit comes from a heat sensing pit behind the nostril used to find prey. When venom is released, local damage is done by metalloproteinases, phospholipase A2, serine proteases, and hyaluronidase which lead to local tissue edema and swelling from capillary damage.2-4 Approximately 25% of bites are “dry bites,” with no venom released. Crotalus scutulatus, also known as Mohave rattlesnakes, are indigenous to the deserts of the western United States and Mexico. They contain a neurotoxic-hemolytic venom, which may lead to vision abnormalities, difficulty with swallowing, and even respiratory failure.5

In the wilderness setting, local care and evacuation must be initiated. Jewelry should be removed from the entirety of the affected limb. If erythema is present, it may be helpful to mark the leading edge and notice of the time for tracking of progression. If possible, immobilize the limb in a neutral position. Though some may have heard to do the following, you should refrain from catching the snake, drinking alcohol, cutting a wound to suck out the venom, applying tourniquets, or attempting to use an electric shock.6 Assessment at a medical facility with labs and monitoring is warranted, and typically will consist of labs to assess coagulopathy as well as consideration of antivenom.3, 4

Scorpion

A 4-year-old girl is brought to an ED in Phoenix, Arizona, with agitation and foot pain. She is tachypneic, restless, and drooling, and on exam you note tongue fasciculations, multidirectional nystagmus, and a small area of erythema on her right foot. What animal is likely responsible for her symptoms?

This child has likely suffered a bark scorpion envenomation. Centruroides sculpturatus is endemic to the American southwest, especially Arizona, Texas, Nevada, California, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.7 Scorpion venom is a complex mix of many substances, but the most clinically important is a heat-stable and protease-resistant neurotoxin.8 This neurotoxin targets axonal sodium channels, increasing the firing of axons by widening and prolonging the action potential and leading to increased release of catecholamines.8 There is a wide spectrum of symptoms including local pain/paresthesia as well as:

- Neuromuscular abnormalities - agitation, skeletal muscle fasciculation, motor hyperactivity (flailing movements, tetanus-like spasms), rhabdomyolysis

- Autonomic dysfunction - tachycardia, hypertension, vomiting, hypersalivation

- Cranial nerve abnormalities - opsoclonus (roving, multidirectional eye movements), blurred vision, tongue fasciculations, dysarthria, stridor, pharyngeal spasm, dysphagia, hyposmia, and dysgeusia.8-11

While adults are stung more often, children are more likely to have more severe symptoms.8, 12 The mainstay of treatment is supportive care, analgesia, and possible benzodiazepines if needed to reduce neuromuscular hyperactivity.8 In severe cases, an FDA-approved antivenom is available for use after consulting with a regional poison control center.13

Gila Monster

A distraught mother and friend of yours video calls to show you her son with an animal latched onto his arm from the backyard. They recently bought a home with a pool in the Southwest United States. You immediately recognize the color pattern is consistent with a Gila Monster. What do you do next?

This is a Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), is a sluggish lizard commonly found in Southwest United States and Northwest Mexico. Typically biting when agitated, they will latch on and chew onto tissue activating the release venom and can be difficult to remove. This may lead to pain, edema, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, weakness, and diaphoresis.14

When bit, it may be difficult to remove. Submersion in water or prying open the mouth may be necessary.15 There have been historical reports of using gasoline in the mouth, flame on the chin or underbelly, and pulling on the tail but these should not be done.16, 17 Irrigation and medical attention is recommended immediately. There is no antivenom available and treatment is supportive. The affected area should be elevated to heart level. Suction or compression for treatment is unproved, and cryotherapy, tourniquet, and excision can be dangerous.15

Black Widow Spider

A 27-year-old woman presents to the ED with muscle pain. She was gathering firewood near her campsite in eastern Texas when she suddenly felt a mild pain on her left arm. About one hour later she developed left arm muscle pain and paresthesia, diffuse abdominal pain, and nausea. On exam she has a tender and rigid abdomen, and you note a small area of erythema with a blanched center and small central punctum on her left volar forearm. What is responsible for her symptoms?

This patient was likely bitten by a black widow spider. Spiders in the Latrodectus species are found in warm climates worldwide, with the most common in the United States being the southern black widow (L. mactans) and the western black widow (L. hesperus). These spiders collectively range throughout the southern and western United States and are easily recognizable by their black bodies with red, hourglass-shaped abdominal markings.18 Black widow venom contains excitatory neurotoxins which stimulate massive exocytosis of multiple neurotransmitters from presynaptic nerve terminals.19 Symptoms can include muscle pain and intermittent rigidity, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and autonomic dysfunction. The typical appearance of the bite is a blanched circular patch with surrounding red perimeter and central punctum. Local diaphoresis and lymphadenopathy may also be present. Treatment is generally supportive, consisting of oral analgesia, benzodiazepines, antiemetics, local wound care, and tetanus prophylaxis if indicated. Antivenoms are available and may be used in moderate to severe envenomations after consulting with a regional poison control center.20

Asian Giant Hornet

A 38-year-old man presents to the ED after 3 days of progressively decreased urination. He was in Northern India 3 days ago when he was attacked by a group of insects, and since returning to the US yesterday has also developed ankle swelling, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. He has approximately 8-10 small, tender areas of erythema and edema on his trunk and upper extremities. What animal is responsible for his symptoms?

This patient was likely stung multiple times by the Asian giant hornet, colloquially called the “murder hornet.” Vespa mandarinia is native to China, India, Japan, Russia, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Nepal, and other South and East Asian countries, but there have been a number of reports of these wasps in British Columbia and Washington State in 2019 and 2020.21-23 Wasp venom contains several active components and can result in conditions ranging from local type I hypersensitivity reactions to anaphylaxis.24, 25 Systemic reactions such as shock, rhabdomyolysis, coagulopathies, respiratory distress, hepatitis, and acute kidney injury are possible especially with multiple stings.24, 26, 27 Treatment is symptomatic and supportive (often including glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and IV fluids), as there is no anti-venom available.24, 26, 27

Coral Snake

"Red on yellow? Red on black? Jack?" Your friend sustained a bite from a snake yesterday while visiting a friend in Florida. He couldn’t remember the riddle but started feeling paraesthesias, nausea, and vomiting after 12 hours. He sends you this picture and asks if he should anticipate staying in the hospital.

The Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius) as described here with red adjacent to yellow, commonly confused with the Scarlet King Snake or the Milk Snake, which has red adjacent to black. The “Red on Yellow, Kill a Fellow, Red on Black, Friend to Jack” rhyme is generally true but there are morphology variants of coral snakes that do not follow this pattern. They possess small, fixed front fangs and may chew to envenomate. Coral snakes have a venom that binds to acetylcholine receptors and is neurotoxic. Around 20-25% of the time, the bite may be a dry bite.28, 29

Typically after envenomation, there are minimal local symptoms, and symptoms may develop up to 12 after the exposure.30 Symptoms can include swelling, paresthesias, nausea, vomiting, euphoria, weakness, dizziness, diaphoresis, muscle tenderness, fasciculations, confusion. In worst case scenarios, bulbar paralytic symptoms, extremity paralysis, and possible respiratory failure.28

Treatment involves immobilizing the extremity, marking the erythema, and removing any jewelry. Do not to suck the venom, submerge in warm water, use tourniquets, take NSAIDs, or splint the affected extremity. Some suggest that all need to be admitted to the hospital due to delayed symptoms, and some may need antivenom.31 Some may advocate for a 8-12 hour monitoring period in the ED with assessments for compartment syndrome and coagulopathies, and if discharged, with strict return precautions.32

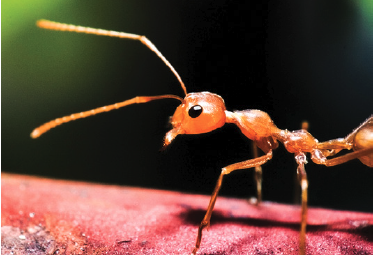

Fire Ant

A 72-year-old man with a history of dementia presents to an ED in Mississippi with painful, pruritic lesions on his feet. He was found 20 minutes prior to arrival sitting on a bench outside his assisted living facility. On both of his feet there are numerous wheals with surrounding erythema, which developed into pustules the next day. What animal is responsible for these findings?

This patient was bitten by fire ants. The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta), black imported fire ant (Solenopsis richteri), and a hybrid species are found in many states in the southern and southeast US, and as far west as California.33 They are generally aggressive, swarming and stinging even without provocation. Ant bites are more common in children, but less mobile patients are at higher risk; there have been several recent reports of attacks on nursing home residents.34

The venom is 95% water-insoluble alkaloid which is cytotoxic and hemolytic, and 5% allergenic aqueous protein solution. The immediate response (IgE-mediated) is a dermal flare and wheal, with papules forming within 2 hours, vesicles within 4 hours, and pustules within 24 hours. There can be large local reactions of pain, erythema, and edema, and they can also cause systemic anaphylaxis. Interestingly, anaphylaxis more commonly occurs in those with prior ant or yellow jacket stings due to venom cross-reactivity.

Fire ant stings can rarely cause serum sickness, nephrotic syndrome, seizures, and exacerbation of pre-existing cardiopulmonary disease. Treatment is firstly to remove any remaining ants, as they can sting repeatedly. Topical antihistamines and corticosteroid creams are sufficient for local reactions, and anaphylaxis should be treated appropriately. The sterile pustules should be left alone but should be cleaned with soap, water, and an antibiotic cream if broken.33

Stingray

You are walking along the beach and you see a couple taking wedding photos with their feet in the water at a Louisiana beach. The bride shouts and looks down and sees a stingray next to her leg. The photographer catches this photo before it swims away.

Stingrays are found in coastal tropical and subtropical marine waters around the world, with 24 different species found in the US.35, 36 When envenomated, the stinger punctures the skin and introduces a heat labile venom. This commonly occurs when stingrays are stepped on in shallow water and shuffling your feet may decrease your likelihood of getting stung. Effects are typically limited to just local effects including pain, irritation, erythema out of proportion to the wound but vary by species. Maximal pain is usually experienced at 30-90 minutes.37 If systemic effects occur, they may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, diaphoresis, weakness, headache, vertigo, abdominal pain, syncope, cramping, and in worst case scenarios, seizures, respiratory distress, hypotension, convulsions, paralysis, cardiac arrest.38, 39

Management should start with rinsing in tap water, or if unavailable, salt water. Warm and hot soaks, ideally as hot as tolerated should be applied. Oral narcotics or local anesthesia may be used. The affected individual be evaluated by a medical professional to ensure their tetanus is up to date, evaluated for retained foreign bodies, and supportive care.37 Prophylactic antibiotics are controversial. Since the venom is heat labile, the wound should be immersed in hot water as soon after the injury as possible, be careful as to not cause further injury by scalding: 45° for 30-90 minutes is recommended. Removal of the barb may be attempted and tetanus should be updated.40, 41 Urine, as well as other historically suggested treatments such as application of numerous substances: macerated cockroaches, fish liver, tobacco juice, cactus juice, gasoline, wine, and cryotherapy are not recommended.40, 41

Box Jellyfish

You and your friends walk across the street to the beach in Florida after eating at a seafood restaurant. Your friend walks out of the water with a jellyfish wrapped around his leg. You immediately run over to provide aid, and you’re being asked what can be done to aid the victim, and if urine can be used to “neutralize” the venom.

Classically, jellyfish stings cause local pain up to 8 hours with linear welts which can progress to blistering and necrotic areas. The specific venom components and mechanisms are unclear, but it’s thought to affect sodium, potassium, and calcium channels at cell membranes. Classically, it causes local pain up to 8 hours with linear welts that can progress to blistering and necrotic areas. Sometimes, if involving > 10% body surface area, systemic effects may take place, including cardiac arrhythmia, hypotension, shock, tachycardia, respiratory dysfunction, death. These usually manifest within 5 minutes of the sting.42

There are many different species of box jellyfish depending on location so following local guidelines are recommended. The American Heart Association–American Red Cross International Consensus on First Aid Science currently advocates vinegar or baking soda slurry followed by the application of heat (or an ice pack if heat is not available) for all jellyfish stings in North America and Hawaii.43 Be wary of using vinegar because some studies suggests it may worsen symptoms.44 Try to control the pain with oral agents if available, and hot or cold packs or water may help.43, 45 Topical lidocaine and how water has shown to help in multiple studies.46 Pressure bandages should not be used.47 Other potential options with unclear benefit for treating symptoms include commercial products with aluminum sulfate48, papain49, lidocaine hydrochloride44, baking soda50, deionized water, seawater, meat tenderizer.48 In some hospital settings, antivenom has been administered, which is a bovine IgG Fab.51

Fire Coral

A 16-year-old boy just got a job at a fish aquarium and comes in with intense forearm pain after cleaning a fish tank with coral. Other than local pain, he has no other symptoms and has normal vital signs.

Fire coral (Millepora alcicornis) has a white to yellow or green exoskeleton and exists around the world. It contains dactylozooids, which are small tentacles, in the exoskeleton. Envenomation occurs via nematocysts, similar to jellyfish. The venom has hemolytic, dermonecrotic, and cytotoxic effects. Since they are rigid, many injuries occur after abrading the structure.52, 53 The envenomation is immediate and painful, and also is associated with pruritus, urticaria, blistering.54 In severe cases, pulmonary edema, hypotension, fever, and renal failure may occur.55, 56

Pain and sensitivity may last months but systemic symptoms are rare. Treatment is mostly extrapolated from nematocysts of other Cnidarians such as jellyfish. Like jellyfish, both hot and cold water are beneficial, as are oral agents, topical lidocaine, and steroids.52 Lacerations are common, and should be irrigated and closed loosely. Antibiotics are recommended to cover skin and aquatic flora and tetanus should be updated. If no systemic symptoms present, patients may be discharged.

References

- Western Diamond Backed Rattlesnake. Encyclopedia of Life https://eol.org/pages/795269

- Bjarnason JB, Hamilton D, Fox JW. Studies on the mechanism of hemorrhage production by five proteolytic hemorrhagic toxins from Crotalus atrox venom. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. May 1988;369 Suppl:121-9.

- Swenson S, Markland FS. Snake venom fibrin(ogen)olytic enzymes. Toxicon. Jun 2005;45(8):1021-39. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.027

- Teixeira C, Cury Y, Moreira V, Picolob G, Chaves F. Inflammation induced by Bothrops asper venom. Toxicon. Dec 2009;54(7):988-97. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.05.026

- Gold BS, Wingert WA. Snake venom poisoning in the United States: a review of therapeutic practice. South Med J. Jun 1994;87(6):579-89. doi:10.1097/00007611-199406000-00001

- Venomous Snakes - Symptoms and First Aid. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 5 January 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/snakes/symptoms.html

- Kang AM, Brooks DE. Geographic Distribution of Scorpion Exposures in the United States, 2010-2015. Am J Public Health. 12 2017;107(12):1958-1963. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304094

- Skolnik AB, Ewald MB. Pediatric scorpion envenomation in the United States: morbidity, mortality, and therapeutic innovations. Pediatr Emerg Care. Jan 2013;29(1):98-103; quiz 104-5. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31827b5733

- O'Connor A, Ruha AM. Clinical course of bark scorpion envenomation managed without antivenom. J Med Toxicol. Sep 2012;8(3):258-62. doi:10.1007/s13181-012-0233-3

- O'Connor AD, Padilla-Jones A, Ruha AM. Severe bark scorpion envenomation in adults<sup/>. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 03 2018;56(3):170-174. doi:10.1080/15563650.2017.1353095

- Hurst NB, Lipe DN, Karpen SR, et al. Centruroides sculpturatus envenomation in three adult patients requiring treatment with antivenom. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 04 2018;56(4):294-296. doi:10.1080/15563650.2017.1371310

- Curry SC, Vance MV, Ryan PJ, Kunkel DB, Northey WT. Envenomation by the scorpion Centruroides sculpturatus. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1983-1984 1983;21(4-5):417-49. doi:10.3109/15563658308990433

- Coorg V, Levitan RD, Gerkin RD, Muenzer J, Ruha AM. Clinical Presentation and Outcomes Associated with Different Treatment Modalities for Pediatric Bark Scorpion Envenomation. J Med Toxicol. 03 2017;13(1):66-70. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0575-3

- Hooker KR, Caravati EM, Hartsell SC. Gila monster envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. Oct 1994;24(4):731-5. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70285-3

- Strimple PD, Tomassoni AJ, Otten EJ, Bahner D. Report on envenomation by a Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) with a discussion of venom apparatus, clinical findings, and treatment. Wilderness Environ Med. May 1997;8(2):111-6. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(1997)008[0111:roebag]2.3.co;2

- LOWE CH, LIMBACHER HP. The treatment of poisonous bites and stings. II. Arizona coral snake and Gila monster bite. Ariz Med. May 1961;18:128-31.

- Stahnke HL, Heffron WA, Lewis DL. Bite of the Gila monster. Rocky Mt Med J. Sep 1970;67(9):25-30.

- Garb JE, González A, Gillespie RG. The black widow spider genus Latrodectus (Araneae: Theridiidae): phylogeny, biogeography, and invasion history. Mol Phylogenet Evol. Jun 2004;31(3):1127-42. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.012

- Südhof TC. alpha-Latrotoxin and its receptors: neurexins and CIRL/latrophilins. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:933-62. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.933

- Clark RF, Wethern-Kestner S, Vance MV, Gerkin R. Clinical presentation and treatment of black widow spider envenomation: a review of 163 cases. Ann Emerg Med. Jul 1992;21(7):782-7. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81021-2

- Smith-Pardo AH, Carpenter JM, Kimsey L. The Diversity of Hornets in the Genus Vespa (Hymenoptera: Vespidae; Vespinae), Their Importance and Interceptions in the United States. Insect Systematics and Diversity. 9 May 2020 2020;4(3)doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isd/ixaa006

- 2020 Asian Giant Hornet Public Dashboard. Washington State Department of Agriculture. Accessed 28 December 2020, https://agr.wa.gov/departments/insects-pests-and-weeds/insects/hornets/data

- WSDA Entomologists Eradicate First Asian Giant Hornet Nest. Washington State Department of Agriculture; 26 October 2020, 2020. Accessed 27 December 2020. https://agr.wa.gov/about-wsda/news-and-media-relations/news-releases?article=31892

- Gong J, Yuan H, Gao Z, Hu F. Wasp venom and acute kidney injury: The mechanisms and therapeutic role of renal replacement therapy. Toxicon. May 2019;163:1-7. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.03.008

- Vikrant S, Parashar A. Two Cases of Acute Kidney Injury Due to Multiple Wasp Stings. Wilderness Environ Med. Sep 2017;28(3):249-252. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2017.05.007

- Vikrant S, Parashar A. Wasp venom-induced acute kidney injury: a serious health hazard. Kidney Int. 11 2017;92(5):1288. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.035

- Dhanapriya J, Dineshkumar T, Sakthirajan R, Shankar P, Gopalakrishnan N, Balasubramaniyan T. Wasp sting-induced acute kidney injury. Clin Kidney J. Apr 2016;9(2):201-4. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfw004

- Kitchens CS, Van Mierop LH. Envenomation by the Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius). A study of 39 victims. JAMA. Sep 1987;258(12):1615-8.

- Parrish HM, Goldner JC, Silberg SL. Poisonous snakebites causing no venenation. Postgrad Med. Mar 1966;39(3):265-9. doi:10.1080/00325481.1966.11695723

- Parrish HM, Khan MS. Bites by coral snakes: report of 11 representative cases. Am J Med Sci. May 1967;253(5):561-8.

- Antivenin (Micrurus fulvius) (Equine Origin) North American Coral Snake Antivenin. Marietta, PA1983.

- Lavonas EJ, Ruha AM, Banner W, et al. Unified treatment algorithm for the management of crotaline snakebite in the United States: results of an evidence-informed consensus workshop. BMC Emerg Med. Feb 2011;11:2. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-11-2

- StatPearls. 2020.

- deShazo RD, Kemp SF, deShazo MD, Goddard J. Fire ant attacks on patients in nursing homes: an increasing problem. Am J Med. Jun 2004;116(12):843-6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.026

- Robins CR, Ray GC, Douglass J. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. 1986.

- Eschmeyer WN, Herald ES, Hammann H. A Field Guide to Pacific Fishes of North America. Houghton Mifflin; 1983.

- Bitseff EL, Garoni WJ, Hardison CD, Thompson JM. The management of stingray injuries of the extremities. South Med J. Apr 1970;63(4):417-8. doi:10.1097/00007611-197004000-00017

- Auerbach PS. Hazardous marine animals. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Aug 1984;2(3):531-44.

- Ikeda T. Supraventricular bigeminy following a stingray envenomation: a case report. Hawaii Med J. May 1989;48(5):162, 164.

- Atkinson PR, Boyle A, Hartin D, McAuley D. Is hot water immersion an effective treatment for marine envenomation? Emerg Med J. Jul 2006;23(7):503-8. doi:10.1136/emj.2005.028456

- Russell F, Lewis R. Evaluation of the current status of therapy for stingray injuries. Venoms. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci Washington, DC; 1956:43.

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Burnett HW. Jellyfish envenomation syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. Jan 1986;14(1):100-6. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70013-3

- Markenson D, Ferguson JD, Chameides L, et al. Part 13: First aid: 2010 American Heart Association and American Red Cross International Consensus on First Aid Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. Oct 2010;122(16 Suppl 2):S582-605. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971168

- Birsa LM, Verity PG, Lee RF. Evaluation of the effects of various chemicals on discharge of and pain caused by jellyfish nematocysts. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. May 2010;151(4):426-30. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.01.007

- Isbister GK, Palmer DJ, Weir RL, Currie BJ. Hot water immersion v icepacks for treating the pain of Chironex fleckeri stings: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. Apr 2017;206(6):258-261. doi:10.5694/mja16.00990

- Ward NT, Darracq MA, Tomaszewski C, Clark RF. Evidence-based treatment of jellyfish stings in North America and Hawaii. Ann Emerg Med. Oct 2012;60(4):399-414. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.04.010

- Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J. Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri. Med J Aust. Jan 1980;1(1):15-20.

- Thomas CS, Scott SA, Galanis DJ, Goto RS. Box jellyfish (Carybdea alata) in Waikiki. The analgesic effect of sting-aid, Adolph's meat tenderizer and fresh water on their stings: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hawaii Med J. Aug 2001;60(8):205-7, 210.

- Nomura JT, Sato RL, Ahern RM, Snow JL, Kuwaye TT, Yamamoto LG. A randomized paired comparison trial of cutaneous treatments for acute jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings. Am J Emerg Med. Nov 2002;20(7):624-6. doi:10.1053/ajem.2002.35710

- Burnett JW, Rubinstein H, Calton GJ. First aid for jellyfish envenomation. South Med J. Jul 1983;76(7):870-2. doi:10.1097/00007611-198307000-00013

- Winter KL, Isbister GK, Jacoby T, Seymour JE, Hodgson WC. An in vivo comparison of the efficacy of CSL box jellyfish antivenom with antibodies raised against nematocyst-derived Chironex fleckeri venom. Toxicol Lett. Jun 2009;187(2):94-8. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.02.008

- Kropp LM, Parsley CB, Burnett OL. Millepora species (Fire Coral) Sting: A Case Report and Review of Recommended Management. Wilderness Environ Med. Dec 2018;29(4):521-526. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2018.06.012

- Nelson L, Goldfrank LR. Marine Envenomations. Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. Eleventh Edition ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Addy JH. Red sea coral contact dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. Apr 1991;30(4):271-3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04636.x

- Hernández-Matehuala R, Rojas-Molina A, Vuelvas-Solórzano AA, et al. Cytolytic and systemic toxic effects induced by the aqueous extract of the fire coral Millepora alcicornis collected in the Mexican Caribbean and detection of two types of cytolisins. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:36. doi:10.1186/s40409-015-0035-6

- Prasad GV, Vincent L, Hamilton R, Lim K. Minimal change disease in association with fire coral (Millepora species) exposure. Am J Kidney Dis. Jan 2006;47(1):e15-6. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.025