As providers on the front line in the emergency department, resident physicians need to pause and understand the process of petitioning patients for psychiatric placement, as this is essential to better treat patients with psychiatric diagnoses.

The patient beds are lining the hallway; another code is underway. The list of patients to be seen is growing. The next patient is a 20-year-old male, a first-time patient, presenting with hand pain. He is disheveled and while talking under his breath, he paces back and forth. Initially, he is oblivious to anyone else’s presence but upon approach, he turns and says the FBI is following him, and that he came here so they could not find him. He is unwilling to answer medical history questions and continues to be internally preoccupied. The patient complains of no pain or recent head trauma. He is oriented to self, time, and place but is uncooperative with the remainder of the mental exam. The musculoskeletal and neurological exams are unremarkable. His urine drug screen is negative and TSH, B12, CMP, and CBC are within normal limits. While reviewing his chart, he becomes agitated, begins screaming at the wall, and says the FBI is present in his room. He receives 5 mg IM Haldol and begins to relax. The differential diagnosis includes but is not limited to ingestion, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder with psychosis, schizophreniform disorder, and brief psychotic disorder.

Other patients are seen and workups and treatment plans pursued. Weighing the options for disposition, it is determined that he must be petitioned for an involuntary inpatient psychiatry hospitalization.

As providers on the front line in the emergency department, resident physicians need to pause and understand this process of petitioning patients as this is essential to better treat patients with psychiatric diagnoses. It is also vital to keep patients and staff safe, all while pursuing best practice when treating psychiatric patients in the ED.

Prevalence in the ED

Throughout the United States, for every 100,000 people, there are 10.5 psychiatrists.1 This lack of psychiatrists and subsequent difficulty accessing care leads those suffering from psychiatric disorders to present to the emergency department. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 1 in 5 adults in the U.S. experience mental illness and one in every 25 from serious mental illness.2 Many patients with mental health symptoms will be seen by their primary care doctor, but many will be seen with decompensated psychiatric illness in the emergency department. The challenge of disposition presents with lack of psychiatric beds and facilities across the nation leading to psychiatric holding in the ED, an issue that has national attention with novel solutions pursued. Along with the lack of trained mental health staff, these patients fill our emergency department beds, leading to limited flow and efficiency.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality states that 1 in 8 ED visits involves a psychiatric emergency.3 Assuming a physician works a 12-hour shift, she or he is highly likely to see at least one patient per shift for a psychiatric emergency. Residents across the country likely can think no further than their last shift where they treated a patient with a psychiatric complaint. Due to the shortage of inpatient and outpatient mental health treatment options, the ED often becomes the only resort for these patients to obtain some intervention. A 2016 online survey of 1,700 ED physicians showed that less than 17 percent of those providers surveyed had a psychiatrist on call to respond to psychiatric emergencies.4 Regardless of whether the patient is held in the ED or transferred to a psychiatric facility, the ability of the ED provider to know and understand the petition process for an involuntary patient for care is paramount. Telemedicine is beginning to fill this role as well as emergency departments opting to use their observation areas to have a psychiatrist evaluate these patients.

Petitioning the Patient

Each state has different policies for petitioning patients for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Being aware of these procedures can improve the quality of care for these patients and decreases stress for the provider and staff. Petitioning patients who meet the criteria allows for the initiation of care either in the ED or in a psychiatric facility. Arizona was ranked the second-highest of all states for the prevalence of mental illness in 2017 by Mental Health American, yet has some of the most liberal involuntary commitment statutes in the U.S. Arizona laws will be used as an example of the petitioning process.5 We encourage each resident to review his or her state for more information on the petition process. More information can be found here: https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org.

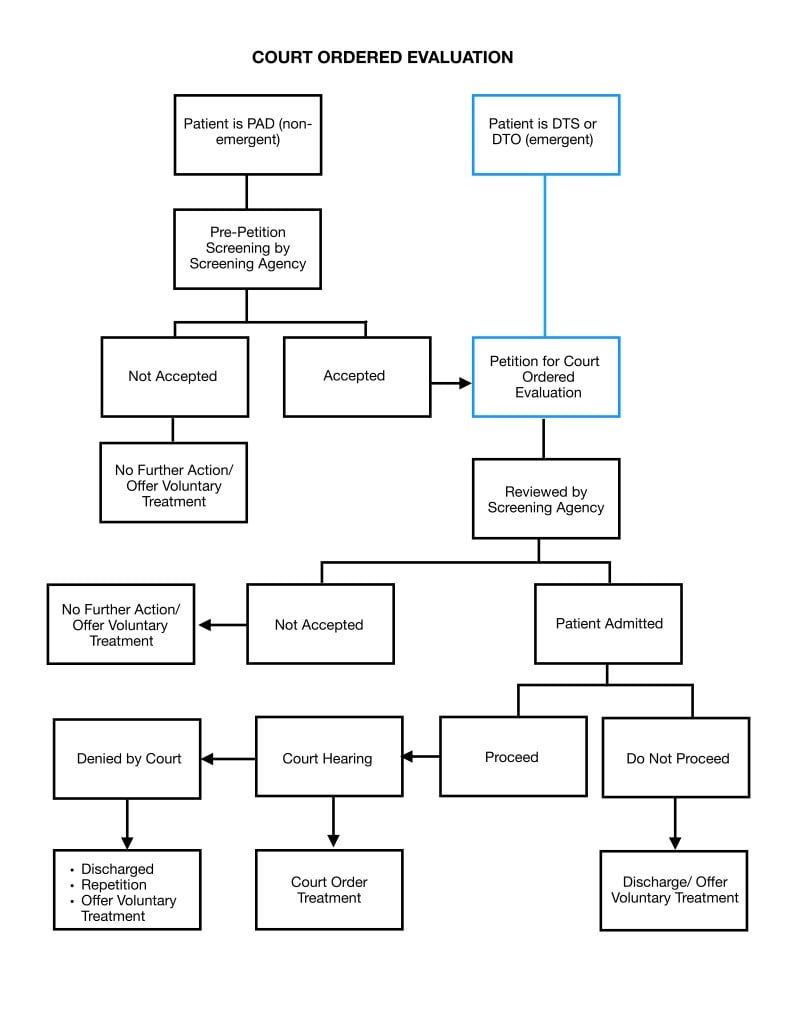

If a patient is deemed to require inpatient psychiatry treatment due to a mental disorder and is unwilling or incapable of consent, is a Danger to Self (DTS), Danger to Others (DTO), Persistently or Acutely Disabled (PAD), or Gravely Disabled (GD), then he or she has met the criteria for Court Ordered Evaluation (COE), also known as a petition.6 (See key terms list for definitions.) COE allows for an involuntary evaluation by psychiatrists within 72 hours, excluding holidays and weekends. If the patient meets the aforementioned criteria, then the recommendation of Court Ordered Treatment (COT) will be made to the probate court. COT lasts a minimum of one year with both a period of inpatient and outpatient treatment. If a patient is DTS or DTO the petition is considered "emergent" and he/she will be taken to a designated psychiatric facility within a prescribed time frame (in Arizona that is 72 hours). If the patient falls under the other two categories (called standards), the patient is considered "non-emergent" and authorities (ie, local police) have up to 14 days, in Arizona, to be transferred.

Figure 1: Schematic of Court Ordered Evaluation in Arizona. Blue boxes show steps likely to be completed by EM providers.

Take-Home Points

With the growing prevalence of mental health illnesses, finding solutions to more effectively handle the burden placed on providers in the ED is a necessity. Many proposed solutions have been offered by the American College of Emergency Physicians, including additional inpatient psychiatric beds, psychiatric education training to ED personnel, increasing availability of outpatient mental health services, creating tele–psychiatry services, and incorporating EmPath units (hospital rooms with home settings including a recliner instead of a hospital bed) in the ED. 7

With continued collaboration between specialties on an inpatient and outpatient basis, mental health crises might be mitigated and patients will receive the appropriate care outside of the ED. Being educated on and advocating for proper petitioning and placement is one important tool to understand in able to assist patients.

Key Words and Legal Definitions6

Mental Disorder: A substantial disorder of emotional processes, thought, cognition or memory distinguished from

- Conditions which are primarily those of drug abuse, alcoholism or intellectual disability, unless, in addition to one or more of these conditions, the person has a mental disorder.

- The declining mental abilities that directly accompany impending death.

- Character and personality disorders characterized by lifelong and deeply ingrained antisocial behavior patterns, including sexual behaviors that are abnormal and prohibited by statute unless the behavior results from a mental disorder.

Danger to Self (DTS): Behavior that, as a result of a mental disorder, constitutes a danger of inflicting serious physical harm upon oneself, including attempted suicide or the serious threat thereof and is substantially supportive of an expectation that the threat will be carried out. Behavior that will, without hospitalization, result in serious physical harm or serious illness to the person, except that this definition shall not include behavior which establishes only the condition of gravely disabled.

Danger to Others (DTO): The judgment of a person who has a mental disorder is so impaired that he/she is unable to understand his/her need for treatment and, as a result of his mental disorder , his/her continued behavior can reasonably be expected, on the basis of competent medical opinion, to result in serious physical harm to others.

Persistently or Acutely Disabled (PAD): A severe mental disorder that meets all the following criteria: If not treated has a substantial probability of causing the person to suffer or continue to suffer severe and abnormal mental, emotional or physical harm that significantly impairs judgment, reason, behavior or capacity to recognize reality.

Gravely Disabled (GD): A condition evidenced by behavior in which a person, as a result of a mental disorder, is likely to come to serious physical harm or serious illness because he/she is unable to provide for his/her basic physical needs.

References

- Psychiatrists and nurse working in mental health sector (per 100000 population), 2014-2016. who.org. http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/mental_health/psychiatrists_nurses/atlas.html. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Mental health by the numbers. Nami.org. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers. Updated September 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Heslin KC, Stocks C. Trends in emergency department visits involving mental and substance use disorders, 2006–2013. AHRQ.gov. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb216-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorder-ED-Visit-Trends.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Nutt AE. Psychiatric patients wait the longest in emergency rooms, survey shows. Washingtonpost.com. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/10/18/sickest-psychiatric-patients-wait-the-longest-in-emergency-rooms-survey-shows/. Published October 18, 2016. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- 2017 State of mental health in America – ranking the states. Mhanational.org. https://www.mhanational.org/issues/2017-state-mental-health-america-ranking-states. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Levitt G. Rule 11 to Title 36 COE/COT and Title 14 Guardians/Conservators. Powerpoint presentation at: Valleywise Hospital, March 18, 2020.

- Should mental illness be treated in the ER? Genesight.com. https://genesight.com/should-mental-illness-be-treated-in-the-er/. Accessed March18, 2020.