Reading Between the Lines in Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Mastering point-of-care ultrasound image interpretation takes not only knowledge of anatomy and pathology, but also knowledge of basic physics, including sonographic artifacts. Artifacts are parts of the image that do not really exist. Often artifacts are thought of as nuisances that are in the way of the anatomy we are attempting to visualize. However, identifying artifacts and understanding why they exist can at times rule out pathology or point towards important diagnoses.

Reverberation artifacts occur when two interfaces with high acoustic impedance bounce the ultrasound waves between them. A common example is the “A-lines” visualized on thoracic ultrasound. A-lines are the reverberated ultrasound waves that have bounced between the parietal and visceral pleura. Comet tail artifacts are another type of reverberation artifact originating from the pleural surface. Another example of reverberation artifact is known as ring-down artifact and typically originates from small metal objects or air bubbles.1

A-lines are part of the normal sonographic thoracic exam, but reverberation artifacts in other anatomic regions can be pathologic and point toward life-threatening diagnoses.

Case 1

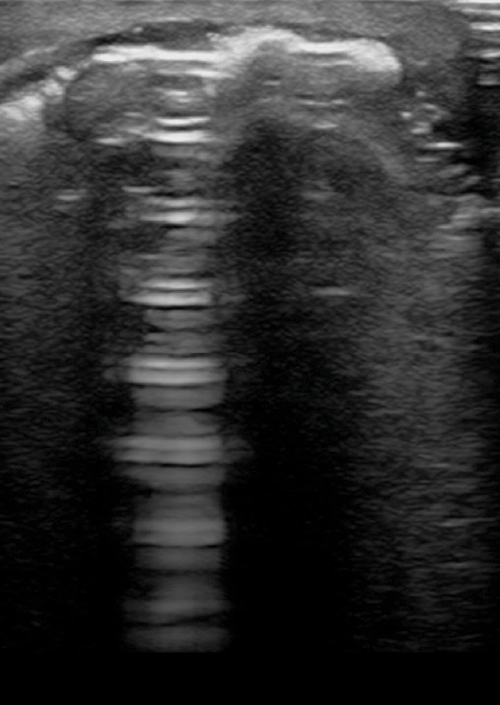

A 38-year-old male presents with worsening arm pain and swelling. You suspect the patient is intoxicated from methamphetamines. He denies IV drug abuse. His right arm demonstrates evidence of significant cellulitis and possible abscess near the antecubital fossa. A bedside ultrasound is performed, followed by a plain radiograph.

The ultrasound (Image 1) demonstrates an impressive reverberation, ring-down artifact, concerning for a retained metal foreign body versus free air. The radiograph confirms free air without retained foreign body. A diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is made, and the patient is taken to the operating room for debridement.

Case 2

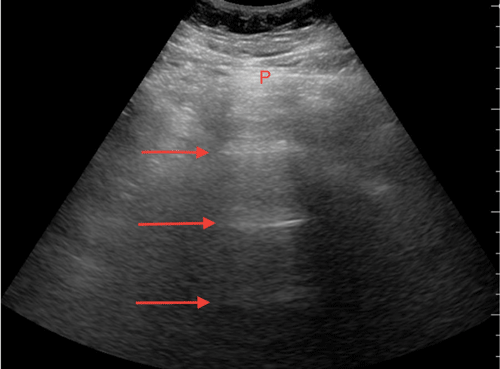

A 45-year-old homeless male with history of alcohol abuse presents for abdominal pain and altered level of consciousness. He quickly becomes unstable and requires both intubation and inotropes before his evaluation can be completed. His abdomen appears soft and mildly distended. A bedside ultrasound is completed to assist in his abdominal pain evaluation. A CT scan was completed after initial stabilization of his vital signs.

This patient demonstrates diffuse abdominal A-lines in all abdominal quadrants. His CT scan demonstrates intestinal pneumatosis of unclear etiology (Image 2). Emergent laparotomy is performed, further demonstrating ischemic gut requiring resection.

Case 3

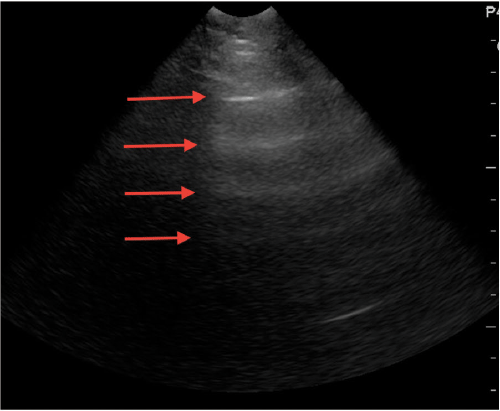

A 54-year-old female with a history of gastric cancer presents for diffuse abdominal pain and worsening distention over the past six hours. The patient is stable, but uncomfortable. Her abdomen is diffusely tender, distended, and tympanic on exam. A bedside ultrasound of the patient is shown (Image 3).

The ultrasound demonstrates diffuse reverberation artifacts in all quadrants. This diffuse abdominal A-line pattern is concerning for intra-abdominal free air, and is confirmed by plain radiograph. It is confirmed that this patient's gastric malignancy had eroded through her bowel wall, and after discussions with the oncologic and surgical services she opts for comfort care measures.

Case 4

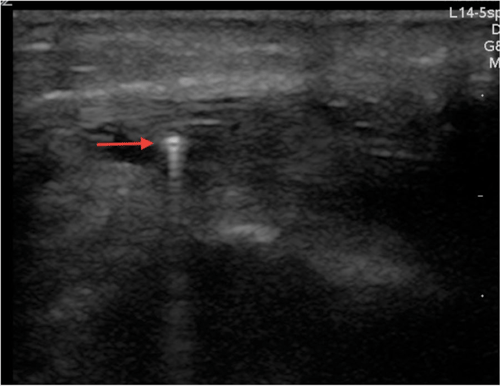

A 10-year-old male was “accidentally” shot in the foot with a BB gun by his older brother. You can visualize the entry wound, but cannot palpate the BB. A bedside ultrasound is performed and shown (Image 4).

A clear reverberation artifact (ring-down artifact) is seen originating from the BB. Locating the foreign body is essential for its extraction.

Case 5

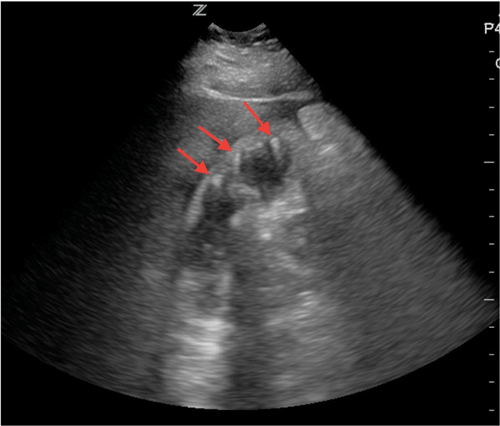

A 48-year-old female presents for right upper quadrant abdominal pain. She appears well, without jaundice, but has a fever and a positive Murphy's sign. A bedside ultrasound is completed as shown (Image 5).

The patient is diagnosed with emphysemtaous cholecystitis and subsequently undergoes an uncomplicated cholecystectomy.

Conclusion

Point-of-care ultrasound is not the test of choice to rule out necrotizing fasciitis, all foreign bodies, or bowel perforation. The sensitivity of ultrasound for these diagnoses will likely never be adequate to be used as a screening tool. However, explicit knowledge of sonographic artifacts such as the reverberation artifact can identify unexpected emergent diagnoses.

It is unclear what role the identification of abdominal A-lines can play in patient management, as this can be a normal finding when loops of gas-filled bowel are adherent to the abdominal peritoneum. However, visualizing abdominal A-lines in every quadrant is concerning for bowel perforation in the cases presented. More research is needed to know whether this finding is clinically relevant, but the prospects are looking bright.

References

- Dawson, Mallin. Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound. 8.6;163-166.