Although commonly thought of only as a health issue, disability is more accurately defined as a complex interaction between physical, intellectual, or emotional impairment with environmental and societal challenges. Individuals with disabilities encounter a variety of daily barriers, including the physical environment (such as wheelchair access), as well as institutional and organizational barriers that hinder access to services.

These patients constitute a marginalized population who experience significant disparities related to health care.1,2 Specifically, those with disabilities experience health disparities and greater unmet needs in comparison to the general population when looking at access to preventative care, interpreter services, and prevalence of certain disease processes (arthritis, asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, oral disease, and stroke).3-8

Traditional beliefs generally associate disability with negative images and experiences. This negativity hinders acceptance, devalues the lives of disabled persons, and undermines possibilities or opportunities for the person who has a disability.

At its extreme, stigmatization may result in abuse, neglect, and exploitation. There is literature to demonstrate that the quality of life and quality of care in those with disabilities are negatively influenced by severity of the patients’ self-perception, poor quality nursing care, negative provider attitudes, and provider disability severity perception.3 This becomes important to remember to help providers refrain from objectifying a patient with a disability.

As health care providers, we should acknowledge and treat the person in his/her entirety and not merely as a disease process. Focusing on the severity of disability or ignoring the true presenting complaint may only perpetuate a lower quality of care and has a negative impact on quality of life. There is also literature to support that improving quality of care may have an even greater impact on improving quality of life than solely changing provider attitudes toward those with disabilities.3

A common source of bias or misunderstanding between health care providers and patients with disabilities relates to differing understandings regarding quality of life. Studies have demonstrated that health care providers overestimate the impact of physical disability on the patient’s quality of life when compared to the patient’s own estimation.9 In one study, 54% of patients with moderate to severe disabilities reported having a good or excellent quality of life.10

So what determines quality of life? Quality of life is an individual construct that is highly dependent on a person’s perceptions, hopes, experiences, and ambitions, as well as their culture and social interactions.

As health care professionals, we interact with and see patients with disabilities in one tiny microcosm of their world, in the hospital or the clinic, where they are the patient who may be ill or suffering. In this brief interaction and with limited information, we may make negative assumptions about their quality of life. In reality, people with disabilities will often tell you that disability and health are not the same thing, and quality of life is not determined in the hospital. We need to be aware of our tendency toward this bias in our approach to patients with disabilities, to ensure that this vulnerable population receives the same treatment as all other populations.

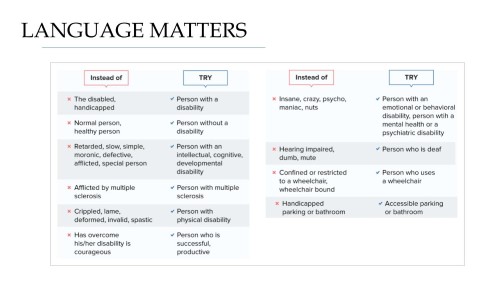

Another source of bias and misunderstanding is language. The language that physicians use when speaking with patients with disabilities is critical in establishing rapport and developing a therapeutic alliance based on mutual respect. In general, person-first language is recommended when speaking to or about persons with disabilities. This means that they are persons WITH disabilities, not disabled persons. A child has Down syndrome; he/she is not a “Down’s child.” This structure recognizes them as a person first, rather than a disability first.

In addition, there are many other commonly used terms that should be eliminated in favor of more appropriate alternatives. For example, instead of “wheelchair-bound,” say “wheelchair-user.” Wheelchairs are tools of mobility and freedom, and we have never seen a patient bound to one. Instead of “handicapped” in reference to parking spaces or bathroom stalls, use “accessible.” Other inappropriate words include crippled, lame, spastic, slow, retarded, crazy, dumb, or mute. Do not refer to persons without disabilities as “normal.” And finally, when speaking to patients with disabilities, whether they be physical, intellectual, psychiatric, or developmental, speak directly to them and do not infantilize them. Make eye contact and presume competence unless you have evidence or data to the contrary.

We can also contribute to establishing rapport by respecting our patients’ expertise. Patients with disabilities possess a lifetime of lived experience with their own disease or condition. Treating a patient (or a family member) as an expert-by-experience allows the person to be viewed before the disability and shows that you, as the physician, respect that experience and insight.11 Some tools to communicate respectfully with your patient include: establishing how they best communicate; speaking directly to the patient; asking if they want their caregiver present; focusing on the patient’s abilities (not their disabilities); and, as always, showing warmth and positive regard.

We encourage everyone to take a moment to reflect on past encounters with patients with disabilities and to think on how future interactions can be improved.

A version of this article was previously published and first appeared in the August 2018 issue of SAEM Pulse, the official membership publication of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

References

- Sterkenburg P, Vacaru V. The effectiveness of a serious game to enhance empathy for care workers for people with disabilities: a parallel randomized controlled trial. Disability and health journal. 2018;11(4):576-582.

- Kang Q, Chen G, Lu J, Yu H. Health disparities by type of disability: health examination results of adults (18-64 years) with disabilities in Shanghai, China. PloS one. 2016;11(5):e0155700.

- Zheng Q-L, Tian Q, Hao C, et al. The role of quality of care and attitude towards disability in the relationship between severity of disability and quality of life: findings from a cross-sectional survey among people with physical disability in China. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2014;12(1):1-10.

- Kersten P, George S, McLellan L, Smith JA, Mullee MA. Met and unmet needs reported by severely disabled people in southern England. Disability and rehabilitation. 2000;22(16):737-744.

- Drum CE, Krahn G, Culley C, Hammond L. Recognizing and responding to the health disparities of people with disabilities. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;3(3):29-42.

- Armour BS, Swanson M, Waldman HB, Perlman SP. A profile of state-level differences in the oral health of people with and without disabilities, in the US, in 2004. Public health reports. 2008;123(1):67-75.

- Reichard A, Stolzle H, Fox MH. Health disparities among adults with physical disabilities or cognitive limitations compared to individuals with no disabilities in the United States. Disability and health journal. 2011;4(2):59-67.

- Froehlich-Grobe K, Lollar D. Obesity and disability: time to act. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;41(5):541-545.

- Rothwell P, McDowell Z, Wong C, Dorman P. Doctors and patients don't agree: cross sectional study of patients' and doctors' perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. Bmj. 1997;314(7094):1580.

- Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Social science & medicine. 1999;48(8):977-988.

- Gona JK, Newton CR, Hartley S, Bunning K. Persons with disabilities as experts-by experience: using personal narratives to affect community attitudes in Kilifi, Kenya. BMC international health and human rights. 2018;18(1):1-12.