A 22-year-old female arrives in your trauma bay in respiratory distress. She appears slightly anxious and is mildly tachypneic. Vital signs are as follows: heart rate of 129 beats per minute, blood pressure of 149/96, respiratory rate 23, and pulse oximetry of 87% on room air. She reports that she has been frequently coughing over the past few weeks but became acutely short of breath since this morning, and has since experienced significant chest comfort. She has no past medical history and takes no medications.

Unfortunately, supplemental oxygen and albuterol do not provide significant improvement. ECG confirms sinus tachycardia without signs of ischemia. A portable chest x-ray looks clear with no suggestion of pneumonia. The decision is made to obtain a computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest for the suspected diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE).

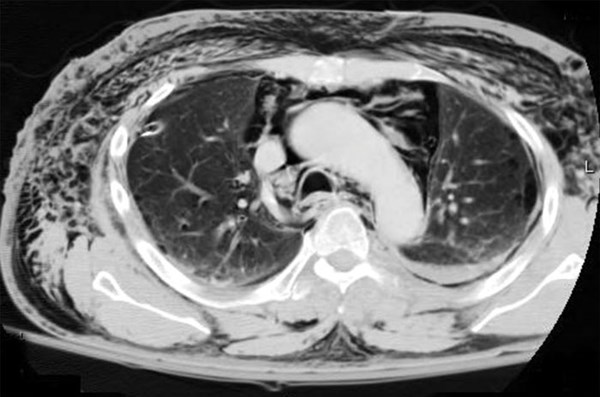

The CT is negative for PE but instead shows “mild-moderate pneumomediastinum of unclear etiology.” Now what?

Pathophysiology

Pneumomediastinum is a rare disease that is defined by air in the mediastinal space. It can be classified as either spontaneous or secondary in nature. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is usually the result of a sudden increase in intrathoracic pressure that causes a subsequent increase in intra-alveolar pressure, leading to alveolar rupture and leakage of air throughout the interstitium, bronchovascular tissue sheath, and mediastinum.1

Studies show that the preceding event is often a sustained valsalva maneuver, such as what occurs with coughing, emesis, forceful defecation, prolonged expiratory phase (asthma), sneezing, or inhalation drug use.1 Secondary pneumomediastinum often is the result of blunt or penetrating trauma, complications from surgical interventions in the esophagus or tracheobronchial tree, intubation, or invasion by gas-forming bacterial organisms.1

Presentation

The presentation of SPM resembles many common complaints seen on an average shift in the emergency department. One study found that in patients with SPM, 54% have chest pain, 39% have dyspnea, and 32% have a cough. The trigger event is emesis 36% of the time, asthma exacerbation in 21%, and unknown 21% of the time.1 The typical patient will most likely be male, with an average age ranging from 20 to 27 years old.1-3 On exam, 32% of these patients will have subcutaneous emphysema.1

Diagnosis and Treatment

The gold standard for diagnosis is CT scan, because up to one-third of cases are not visualized on x-ray.1-3 Once identified, secondary causes must be ruled out. For example, Boerhaave syndrome, a longitudinal tear of the esophagus secondary to an increase in intraesophageal pressure, must be considered as a potential source given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with this disease.4 Accumulation of corrosive gastric contents and gastric flora within the mediastinal and pleural spaces may result in fulminant mediastinitis and septic shock.5 Contrast esophagogram is the study of choice to visualize esophageal rupture.2

Unrecognized SPM could lead to tension pneumomediastinum due to air entering the mediastinum through a valve-like mechanism that is then unable to exit, similar in physiology to a tension pneumothorax.6 Retained air may result in reduced lung capacity and secondary atelectasis as well as compression of the right atrium and vena cava.7

Fortunately, SPM is an exceedingly rare and self-limiting disease. When diagnosed in the emergency department, ABCs must always be prioritized. Often, no significant interventions are required. While the course of treatment is not standardized, admission is generally recommended along with cardiothoracic or general surgery consultation. This is because of the need to rule out secondary causes that may require operative washout or repair of the aerodigestive tract. Bed rest and analgesia are often all the patient needs for recovery, with prophylactic antibiotics as a debated subject in the treatment algorithm.3

Complications are rare, and these patients often have an uneventful recovery course.

Case Resolution

The patient was admitted to the general medicine team with cardiothoracic surgery consulting. An esophagogram was obtained and was normal. The patient improved with supportive care and was discharged on hospital day three in good condition.

In conclusion, while SPM is a rare disorder, it is worth considering on the differential for a young patient presenting to the emergency department with chest pain or shortness of breath. Treatment is often supportive, but life-threatening causes and complications must be ruled out. Proper imaging is essential for diagnosis, and consultation with surgery is generally recommended.

Editor's Note: For a fascinating related case report, see "Post-Intubation Tracheal Tear Leading to Abdominal Compartment Syndrome."

References

- Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Weiman D, Garret Jr HE. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: A comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(3):962-966.

- Jougon JB, Ballester M, Delcambre F, MacBride T, Dromer CEH, Velly JF. Assessment of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: Experience with 12 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(6):1711-1714.

- Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102(9):1329-1334.

- Korn O, Onate JC, Lopez R. Anatomy of the Boerhaave Syndrome. Surgery. 2007;141(2):222-228.

- Curci JJ, Horman MJ. Boerhaave's syndrome: The importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Surg. 1976;183(4):401.

- Gabor SE, Renner H, Maier, A, Juttner FMS. Tension pneumomediastinum after severe vomiting in a 21-year-old female. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28(3):502-503.

- Paluszkiewicz P, Bartosinski J, Rajewska-Durda K, Krupinska-Paluszkiewicz K. Cardiac arrest caused by tension pneumomediastinum in a Berhaave Syndrome patient. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(4):1257-8.