Article

Watts S, Smith JE, Gwyther R, Kirkman E. Closed chest compressions reduce survival in an animal model of haemorrhage-induced traumatic cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. May 2019. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.04.048

OBJECTIVE

To examine the effect of closed chest compressions on cardiac arrest due to hemorrhagic shock versus whole blood resuscitation.

Background

There have been remarkable advancements in trauma resuscitation in the past few decades. From the introduction of the massive transfusion protocol to REBOA we have been making tremendous strides. However, unfortunately, many times we treat a traumatic arrest similar to a medical arrest. This includes performing chest compressions. From a theoretical and pathophysiological perspective, this doesn’t make sense. Performing compressions to circulate the blood doesn’t matter if there is no blood to circulate. In a traumatic arrest then we need to focus on reversible causes that we can fix, e.g. hemorrhage, hypoxia, and obstructive physiology.

Design

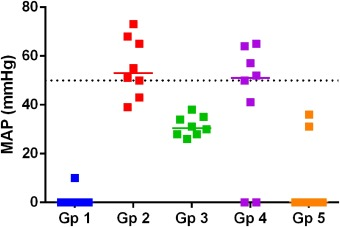

Study Design: Thirty-nine pigs were endotracheally intubated and sedated. After which the pigs received three shots to the thigh from a captive bolt and underwent a controlled hemorrhage (30% of their blood volume). They were kept at a MAP of 45mmHg for 60 minutes. The hemorrhage was collected and preserved for later autotransfusion. The pigs were then further bleed to achieve a MAP of 20mmHg. The decision to initiate resuscitation was performed by a blinded researcher or at the five-minute mark.

Intervention: The animals underwent three cycles of resuscitation. They were randomized into five groups: Group 1 closed chest compressions only, group 2 whole blood, group 3 saline, group 4 whole blood plus compressions, group 5 saline plus compressions. Fluid was given at 10ml/kg and compressions were performed by a LUCAS device. Calcium chloride was administered to keep arterial ionized calcium >1mM. The animals in groups 1,4 and 5 continued with compressions after the third cycle if the MAP <20mmHg. If the MAP >20mmHg then the animals were observed for 15 minutes.

Primary Outcome: Return of Spontaneous Circulation defined as a MAP >50mmHg.

Secondary Outcome:

- Differences in survival and attainment and maintenance of ROSC during the Resuscitation and Post-Resuscitation Phases

- Comparison of the different groups cardiovascular and physiological parameters.

Results

- Primary Outcome: Significant increase in ROSC when whole blood was provided. No significant difference between Group 2 WB only, and Group 4 WB +compressions.

- Secondary Outcomes: Significant improvement in cardiovascular and physiological parameters when whole blood was given over just compressions or saline/saline plus compressions.

Strengths

- Multiple intervention groups.

- Extensively examined a wide range of parameters.

Limitations

- Porcine study.

- Only 39 pigs in the study.

- The endpoint was ROSC as opposed to long-term neurological recovery

- The pigs were not brought to asystole.

- Used whole blood, not component therapy.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that fluid resuscitation with whole blood is significantly better than resuscitation with compressions alone or with normal saline. It further showed that there was no difference between whole blood only resuscitation versus compressions plus whole blood resuscitation.

ED Take Away Points

Traumatic arrests are some of the most challenging cases that EM providers experience. They require multiple procedures and interventions that have to occur almost immediately and simultaneously. This study provides further supports that hemorrhagic shock must be treated by the rapid infusion of blood, which for most of us occurs in the form of a massive transfusion protocol and a rapid infuser. Compressions should not get in the way of critical procedures that can reverse the cause of a traumatic arrest e.g. cordis placement, IO, bilateral thorocostomies or a thoracotomy for obstructive physiology. Compressions do not work if there is no blood to pump or if the blood is being obstructed. Thus, the focus should be on the rapid reversal of causes of traumatic arrest. Compressions should be performed if they do not interfere with these critical procedures or if there is a concern that a medical cause preceded the arrest (eg, a massive MI causing a car accident).