With levels of COVID increasing globally, the full impact of the pandemic on the mental health of frontline workers is still to be determined.

This study sought to assess emergency medicine (EM) physicians and residents in a NY hospital, an area hard-hit by the virus, for COVID-related anxiety during and after the peak of the pandemic.

Methods: An anxiety survey was emailed to all EM physicians and residents at the participating hospital with a total of 50 possible participants. Data was then collected and analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a 95% confidence level and mean comparison.

Results: The mean anxiety score for all participants (n=36) during the pandemic peak was 32.4 compared to 30.9 after the peak (p=0.198). Female (mean=37.1, n=11) versus male (mean=30.4, n=25) anxiety scores during the COVID peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a significant p-value of 0.002. Those participants who reported three or more of the DSM V anxiety symptoms (mean=40.0, n=7) during the pandemic peak had statistically significant higher anxiety scores during the pandemic peak compared to those with less than three symptoms (mean=30.6, n=29) (p=0.0002). Those participants who reported three or more anxiety symptoms after the pandemic peak (n=5) had statistically significantly higher anxiety scores during (p=0.0005) and after (0.0000) the pandemic peak compared to those with less than three symptoms (n=31). 77.8% (n=28) versus 47.2% (n=17) of participants, respectively, reported showing less physical affection (hugging, kissing, hand-holding, etc.) toward their loved ones during and after the COVID peak, and 58.3% (n=21) and 44.4% (n=16) of participants, respectively, reported being treated differently by friends and family as a result of working in a hospital during and after the pandemic. During the pandemic peak, 94.4% (n=34) worried about exposing their loved ones to COVID, while 69.4% (n=25) still worry about exposing their loved ones to COVID.

Conclusions: Participants are experiencing major changes in their home life as a result of the pandemic, including showing less affection to loved ones. While overall participant anxiety levels were not increased, females and those individuals who reported a higher number of anxiety symptoms were found to have higher anxiety scores. More studies are needed to fully assess if these findings are consistent on a larger scale.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, we watched as China began to experience spikes of cases towards the end of December 2019 into early January 2020 and then saw the virus spread rapidly in the early spring of 2020 throughout the world to become the first major pandemic since the flu pandemic of the early 1900s. As of October 2020, globally, an estimated 40 million people have been infected with COVID-19, while an estimated 1.1 million people have lost their lives to the virus. Although the pandemic’s peak may have passed, we are unfortunately starting to see spikes in COVID cases worldwide in countries including the United States, Russia, France, Spain, Iran, Germany, Indonesia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. An increase has not followed these spikes in cases in deaths, but it is difficult to predict what is to come over the next several months and even years as we continue to battle COVID-19.1,2 Now potentially facing another increase in cases, how did the pandemic affect the mental state of our frontline medical workers?

Working in what became the epicenter of the COVID outbreak, New York (NY) emergency department (ED) staff battled against what seemed like endless waves of COVID cases and, for some, even battled the virus themselves. Just like assessing the damage of the aftermath of a war, our frontline workers have emerged on the other side but in what condition? A study by Rodriguez et al.3 was the first study of its kind in the U.S. that sought to assess anxiety and burnout levels as well as homelife changes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in academic emergency medicine (EM) physicians and residents via an emailed survey. The study specifically looked at seven EM residencies and their affiliated institutions in California (5), New Jersey (1), and Louisiana (1) during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (February to April 2020). Their study found that the COVID-19 pandemic induced moderate to severe anxiety with a substantial impact on home life, including worries about exposing family and friends to the virus. Our study sought to assess for COVID-related anxiety experienced by ED physicians and residents in a NY hospital 80 miles north of New York City that was significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It utilized a similar method to the above study by using an emailed survey to assess EM physicians and residents for the signs and symptoms of anxiety. This survey also assessed and evaluated for changes in home life via a series of questions targeting changes in behavior at home due to a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

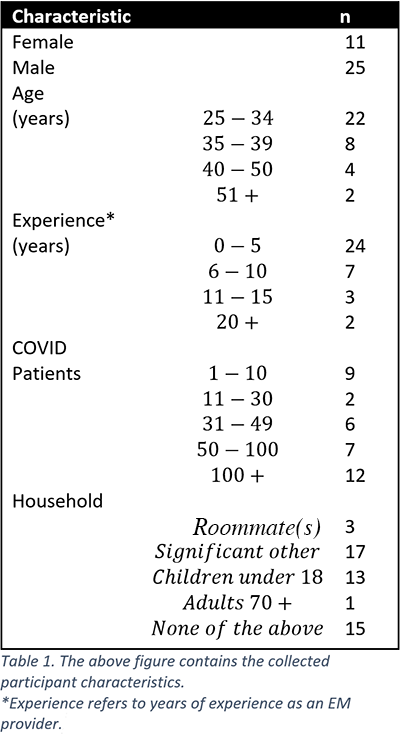

Our study was conducted at Garnet Health Medical Center (GHMC) in Middletown, NY. It included all EM physicians (32) and residents (18), regardless of age, gender, years of experience, etc., who work within the GHMC ED for a total of 50 estimated participants. An anxiety survey was created using the DSM V generalized anxiety disorder symptoms criteria,4 and the Zung self-rating anxiety scale.5 The survey also included ten questions related to home life changes during and after the pandemic's peak and the collection of general variables including participant gender, age, years of experience as an EM provider, estimated COVID positive patient exposure, and household make-up. The general variables collected are as noted in Table 1. Survey questions consisted of yes/no, multiple-choice, and open-ended responses.

Table 1.

To collect the data, the anxiety survey was sent out weekly via email over a month to participants' work email addresses to assure that as many participants as possible were included in the study with the goal of gaining 90% participation. Given that the desired number of participants was not met after a month, the study was extended by 1.5 weeks over which four additional opportunities to fill out the survey were provided via email. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous unless participants revealed their identity for further discussion. This study was deemed IRB exempt prior to the emailing of the survey. Inclusion criteria for participants consisted of EM physicians and residents with the degree of DO or MD currently employed in the ED at GHMC. The study did not include other ED staff such as nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or ER technicians. After the survey was closed for submissions, the data was then summarized and analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a 95% confidence level and mean analysis. Raw anxiety scores were calculated using the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale5 instructions and then converted into the anxiety index scores which then enabled the sorting of anxiety levels into a normal range of 20-44, mild to moderate of 45-59, marked to severe of 60-74 and extreme of 75 and above. Anxiety index scores were compared between various groupings and analyzed for significance.

Results

A total of 36 participants, or 72% of all possible participants, completed the survey. Three out of the 36 participants had anxiety scores that showed mild to moderate anxiety levels (scores of 45-59), while one of 36 participants had an anxiety score in the marked to severe anxiety level (scores of 60-74). All other participants (n=32) had anxiety scores within a normal range, as defined by the Zung Anxiety Scale,5 during and after the pandemic peak. The mean anxiety score for all participants (n=36) during the pandemic peak was 32.4 compared to 30.9 after the peak (p=0.198). Females (mean=37.1, n=11) versus males (mean=30.4, n=25) during the COVID peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a significant p-value of 0.002. Those with <3 anxiety symptoms during the peak (mean=30.6, n=29) versus those with ≥3 anxiety symptoms during the peak (mean=40.0, n=7) both during the pandemic peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a significant p-value of 0.0002. Those with <3 anxiety symptoms after the peak (mean=31.0, n=31) versus those with ≥3 anxiety symptoms after the peak (mean=41.2, n=5) both during the pandemic peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a significant p-value of 0.0005. Those with <3 anxiety symptoms after the peak (mean=31.0, n=31) versus those with 3≤ anxiety symptoms after the peak (mean=41.2, n=5) both after the pandemic peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a significant p-value of 0.0000. All other values were analyzed with an unpaired t-test but were not found to be significant.

Table 2.

| GROUP | AVERAGE ANXIETY SCORE | n | P Value | ||

| COVID Peak | Post Peak | COVID Peak | Post Peak | ||

| Total | 32.4 | 30.9 | 36 | Total p=0.198 | |

| Female | 37.1 | 32.6 | 11 | 0.002++ | 0.210 |

| Male | 30.4 | 30.2 | 25 | ||

| With Children | 34.6 | 31.1 | 13 | 0.075 | 0.371 |

| Without Children | 31.2 | 30.8 | 23 | ||

| With significant other | 33.5 | 30.7 | 17 | 0.198 | 0.444 |

| Without significant other | 31.5 | 31.1 | 19 | ||

| < 30 COVID Patients | 30.4 | 28.4 | 11 | 0.112 | 0.114 |

| > 30 COVID Patients | 33.4 | 32.0 | 25 | ||

| < 10 Years of Experience* | 32.1 | 31.0 | 31 | 0.204 | 0.468 |

| > 10 Years of Experience | 34.8 | 31.2 | 5 | ||

| < 5 Years of Experience* | 31.9 | 31.5 | 24 | 0.241 | 0.266 |

| > 5 Years of Experience | 33.6 | 29.7 | 12 | ||

| Age < 40 | 32.7 | 31.4 | 30 | 0.310 | 0.238 |

| Age 40+ | 31.2 | 28.7 | 6 | ||

| Age < 35 | 31.7 | 29.9 | 22 | 0.216 | 0.185 |

| Age 35+ | 33.6 | 32.5 | 14 | ||

| < 3 Anxiety Symptoms (AS) During Peak | 30.6 | 30.2 | 29 | 0.0002++ | 0.141 |

| ≥ 3 AS During Peak | 40.0 | 34.0 | 7 | ||

| < 3 AS After Peak | 31.0 | 29.0 | 31 | 0.0005++ | 0.0000++ |

| ≥ 3 After Peak | 41.2 | 44.2 | 5 | ||

Table 2. The figure provides the comparison of means between groups of interest along with their associated p values during and after the peak of the pandemic. Females (mean=37.1, n=11) versus males (mean=30.4, n=25) during the COVID peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a p-value of 0.002. Those with < 3 anxiety symptoms during peak (mean=30.6, n=29) versus those with ≥3 anxiety symptoms during the peak (mean=40.0, n=7) both during the pandemic peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a p-value of 0.0002. Those with < 3 anxiety symptoms after the peak (mean=31.0, n=31) versus those with ≥3 anxiety symptoms after the peak (mean=41.2, n=5) both after the pandemic peak were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with a p-value of 0.0000. All other values were analyzed with an unpaired t-test but were not found to be significant.

*Experience refers to years of experience as an EM provider

++ Significant p-value

Participants with children (n=13) had a higher mean anxiety score during the COVID peak compared to those without children (n=23) (34.6 vs 31.2, p=0.075) but had a similar mean anxiety score to those without children after the pandemic peak (31.1 vs 30.8, p=0.371). There was no significant difference in anxiety scores during (33.5 vs 31.5, p=0.198) or after (30.7 vs 31.1, p=0.444) the pandemic peak between those with a significant other (n=17) compared to those without a significant other (n=19). Individuals who treated less than 30 COVID patients (n=11) had a lower mean anxiety score compared to those who treated more than 30 COVID patients (n=25) during (30.4 vs 33.4, p=0.112) and after (28.4 vs 32.0, p=0.114) the pandemic peak, while both groups had similar anxiety score means within their own groups, respectively, during and after the pandemic peak. Participants with more years of experience as an EM provider, defined as 0-5 years of experience compared to 5+ versus 10+ years, had a higher average anxiety score compared to those with less experience during the peak of the pandemic (0 to 5 [n=24] vs 5+ years [n=12]: 31.9 vs 33.6, p=0.214) (0-10 [n=31] vs 10+ years [n=5]: 32.1 vs 34.8, p=0.204) but did not have statistically significant higher anxiety scores. All participants regardless of years of experience had similar anxiety scores after the pandemic peak. Age did not play a major factor in predicting anxiety scores as those under age 35 (n= 22) versus 35+ (n=14) and those under age 40 (n=30) versus 40+ (n=6) had similar levels of anxiety during (31.7 vs 33.6, p=0.216; 32.7 vs 31.2, p=0.310) and after (29.9 vs 32.5, p=0.185; 31.4 vs 28.7, p=0.238) the pandemic peak. Please see Table 2 for more details.

During the pandemic peak, 27.8% of participants (n=10) reporting “feeling restless or keyed up or on edge,” while 11.1% (n=4) reported this symptom after the peak. 19.4% (n=7) and 30.6% (n=11), respectively, reported being easily fatigued during and after the pandemic peak. 5.6% (n=2) and 11.1% (n=4), respectively, reported difficulty concentrating or mind going blank during and after the pandemic peak. Irritability was reported by 30.6% (n=11) and 6.7% (n=6) during and after the pandemic peak, respectively, while muscle tension was reported by 22.2% (n=8) and 19.4% (n=7), respectively. 16.7% (n=6) experienced sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless unsatisfying sleep) during the peak, and 11.1% (n=4) experienced sleep disturbance after the peak. 50% (n=18) did not report any of the above symptoms during the pandemic versus 55.6% (n=20) after the pandemic.

77.8% of participants (n=28) reported showing less physical affection (hugging, kissing, hand-holding, etc.) towards their loved ones during the COVID peak compared to 47.2% of participants (n=17) after the peak. Three individuals reported living separately from others who normally reside in their home during the COVID peak, while only one individual reported continuing to live separately from others who normally reside in their home after the peak. 58.3% of participants (n=21) reported being treated differently by friends and family as a result of working in a hospital during the pandemic, while 44.4% (n=16) reported still being treated differently after the peak. 88.9% of participants (n=32) discussed their excess COVID exposure risk with their family and friends during the pandemic, and 80.6% (n=29) still report discussing their excess risk with family and friends. During the pandemic peak, 94.4% of participants (n=34) worried about exposing their loved ones to COVID, while 69.4% (n=25) still worry about exposing their loved ones to COVID.

Discussion

The overall results of the study show that there was no statistically significant difference between the anxiety scores of participants during or after the peak of the pandemic. This remained true for all participants despite having children, having a significant other, being exposed to a lesser or greater number of COVID patients (under vs. above 30 patients), having lesser or greater years of experience, or being younger versus older. Rodriguez et al.3 also found no significant difference between those with or without children or between faculty versus residents/fellows. While our study did not directly measure differences between faculty and residents/fellows, this finding by Rodriguez et al can be interpreted as the responses of those with less experience did not differ from those with more experience. However, Rodriguez et al. did find that the COVID pandemic induced moderate to severe levels of anxiety in EM providers. Barello et al.6 also found that health professionals in Italy who cared for COVID patients felt significant work-related psychological pressure and had frequent associated somatic symptoms which included change in food habits, difficulty falling asleep, irritability, and muscle tension, which were also experienced by our participants. Two studies in Pakistan7 and Spain8 also found increased levels of anxiety/depression in doctors during the COVID peak at prevalence rates of 43% and 21.6%, respectively. While our study did not find that the pandemic led to increased anxiety levels, this difference in results could be explained by 1) our study having a small sample size, 2) participants being from a smaller hospital (fewer patients and/or less overwhelmed compared to larger hospitals), 3) participants having adequate access to personal protective equipment (PPE) throughout the pandemic, 4) participants having a greater sense of community within the ED due to its smaller size providing increased peer support, 5) and/or sampling of the population too far away from the peak of the pandemic leading to recall bias. Despite not seeing a difference in anxiety levels between most groups, our study did show that females had statistically higher anxiety scores during the pandemic compared to males but that they did not demonstrate this difference after the pandemic peak. Several other studies conducted in Italy,6 Spain,8 China,9 Israel,10 and the United States3 also noted this finding of higher anxiety levels in females, which is consistent with the generally higher rates of depression and anxiety in females versus males.11

In contrast to our findings, Amin et al.7 who studied factors associated with anxiety and depression in 389 Pakistani frontline physicians via an online survey found that having young children at home and being in contact with a higher number of COVID patients per day was associated with having anxiety and depression in physicians. They hypothesized that having children at home led to higher levels of anxiety and depression given increased concerns for causing loved ones to become sick at home with COVID. Increased anxiety and depression in relation to seeing more COVID patients could be explained by the reported poor availability of PPE in Pakistani hospitals in combination with greater COVID exposure as 94% of participating physicians reported feeling either completely or to some extent unprotected from COVID. Their study also found that there was no significant difference in anxiety/depression between male and female participants, which is unique in that few studies agree with this finding, and no significant difference between trainees and consultants, again suggesting that years of experience was not a major factor for predicting anxiety levels.

Conclusion

While our study did not show increased anxiety levels among EM providers during or after the COVID pandemic peak, it did show that participants are still experiencing major changes in their home life as a result of the pandemic and that females and those who report a higher number of anxiety symptoms are at higher risk for developing anxiety. With levels of COVID increasing globally, the full impact of the pandemic on the mental health of frontline workers is still to be determined, and more studies will be essential to make sure that we are meeting the mental and emotional needs of our health care workers to better support them in the battle against COVID-19.

Limitations

The primary limitation of the study was the small sample size. Future studies would seek to include a larger population of physicians ideally from multiple hospitals both within and outside of the state of New York. While 72% of possible participants completed the survey (n=36), it was very challenging to get physicians to participate in the study. The survey was sent to each physician’s work email which many reported that they either 1) do not check frequently or at all, 2) receive too many emails to see the survey, 3) don't have time to check their email at work, and/or 4) tend to automatically delete surveys. Many of the survey responses were obtained by personally speaking with physicians about the survey and asking them to complete it. For future surveys, it will be important to assure that either a large enough study group is obtained and/or that the researchers can directly speak with possible survey participants about filling out the survey to help assure adequate participation.

Future studies

Future studies should include continued evaluation of EM physicians on a broader level including sampling from a greater number of hospitals and increasing the sample size to assess if the findings are consistent with our study's findings. Other studies should be conducted to evaluate physicians in both EM and other specialties for depression as well as emotional exhaustion, as increased levels of depression and emotional exhaustion were a common finding among physicians in the studies noted in the discussion. Additional studies should also seek to evaluate other medical professionals including nursing staff who were noted by Barello et al.6 to experience emotional exhaustion more frequently than doctors, which could be linked to nursing staff spending significantly more time with individual patients compared to doctors. Finally, the impact of the pandemic on the loved ones of patients as patient visitation is very restricted in many health care settings should be studied given its possible impact on patient recovery.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Eleonora Feketeova, MD, who provided advice on the development of my research idea and provided guidance throughout the research process including helping with the final editing of this article.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. New Cases of COVID-19 In World Countries. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, et al. Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians Anxiety Levels, Stressors, and Potential Stress Mitigation Measures During the Acceleration Phase of the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(8):700-707.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Table 3.15, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Generalized Anxiety Disorder Comparison - Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Published June 2016. Accessed August 20, 2020.

- Zung WWK. A Rating Instrument For Anxiety Disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371-379.

- Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113-129.

- Amin F, Sharif S, Saeed R, Durrani N, Jilani D. COVID-19 Pandemic- Knowledge, Perception, Anxiety and Depression Among Frontline Doctors of Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20.

- González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:172-176.

- Chen B, Li Q-X, Zhang H, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on medical staff and the general public. Curr Psychol. October 2020.

- Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, et al. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Translational Psy. 2020;10.

- Albert P. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(4):219-221.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, eds. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. 3rd ed. The Scarecrow Press; 1997:191-218. Accessed October 30, 2020.