Medical residents in the United States have the opportunity to learn and practice procedures on simulators before ever attempting them on a real patient. An emergency medicine resident may, for example, utilize a mannequin model in learning to place ultrasound-guided internal jugular (IJ) central venous catheters (CVC) and receive feedback from teachers in a low-stress environment, so that when the resident ultimately performs the procedure on a patient, he or she already has some degree of facility with both the use of ultrasound for vascular access and the performance of the procedure itself.

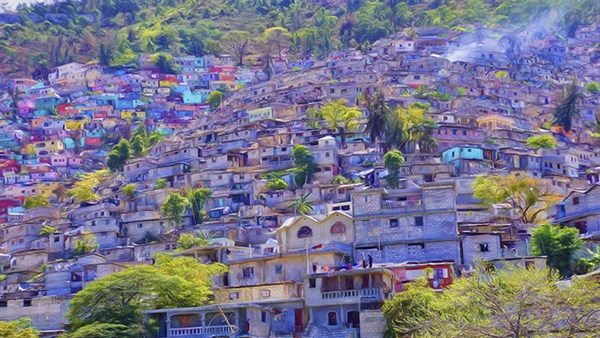

In resource-limited countries like Haiti, however, a lack of physician training in central line placement results in these procedures rarely being done at all. The femoral vein is the site of choice, but these lines are typically placed only by surgeons — when one is available. Subclavian lines are infrequently placed because there's a lack of training in this approach, and IJ lines are virtually unheard of. If a patient lacks peripheral access or needs vasopressor infusion, they are often left without any acceptable alternative, at times limiting therapeutic options. At Bernard Mevs Hospital in Port-au-Prince, where we have volunteered for several years, we saw this health disparity firsthand and strove to find a solution.

After recently renovating the hospital's intensive care unit — now the larger of the two in the country — hospital leadership sent a request for a central line training mannequin and personnel to host a week-long teaching session. This presented an opportunity for us to apply the "train the trainer" model and introduce a potentially valuable clinical intervention modality in a resource-limited setting.

Before agreeing to the request, our group carefully discussed its risk-benefit ratio. With this new modality, we weighed the potential complications (and the learners' abilities to deal with them) versus the potential patient benefits. We ultimately concluded that we would apply a similar assessment to the trainees as would be done in a high-resource setting, to ensure procedural competence while also highlighting potential pitfalls of CVC insertion and management of such complications.

Our week-long training session welcomed 28 physicians from multiple specialties, including emergency medicine, anesthesia, surgery, pediatrics, critical care medicine, and internal medicine, at multiple levels of training, including interns, senior residents, and attending physicians. Our tools included a mannequin from Simulab, with clinically relevant landmarks such as the clavicle and sternal notch, in addition to vascular anatomy that included the internal jugular vein, subclavian vein, and internal carotid artery. Thanks to another recent donation, learners had access to a Sonosite ultrasound machine with a high-frequency linear probe. Additionally, various sized catheters and central line kits were available.

Our sessions were developed to focus on performing ultrasound-guided IJ CVC insertion, as well as landmark-based subclavian CVC insertion. At the beginning of the session, the participants were asked to complete an 8-question pretest, which was designed to assess the pre-course comfort level and knowledge base regarding CVC placement and its complications. We decided to use the checklist assessment model, as opposed to the global rating scale, to evaluate procedural competence. This is because the steps in CVC insertion are usually successive and uniform, making checklists, which are more objective than global ratings scales, better suited for assessment.[1]

Our pretest included two questions designed to gauge the comfort level performing an ultrasound guided IJ CVC or landmark subclavian CVC insertion. Of the participants, all 28 felt uncomfortable with the ultrasound-guided IJ approach. Attitudes about subclavian CVC placement were more varied, with 82 percent of participants not comfortable with its placement and 14 percent comfortable.

The remaining questions tested knowledge of potential complications of CVC insertion and their management, basic knowledge of procedure steps, and specific indications. We found most participants were knowledgeable regarding indications and complications. There was some knowledge deficiency in regard to obstacles that may be encountered during the procedure. For example, one specific question asked about meeting resistance when inserting the guidewire. Only 30 percent of the participants correctly selected to remove the guidewire and recheck blood flow. Another 50 percent of the participants selected to guide the wire past the site of obstruction under sonographic visualization. The prevalence of this incorrect response was thought to be related to poor access to ultrasound machines, limiting the learners' understanding of how they are incorporated into CVC placement and troubleshooting.

The sessions were each 2 hours long, divided over two periods. Extra time was spent with one of the emergency physicians, who had already completed an ultrasound course. This person was designated the lead person for future training sessions after our departure, and would serve as "chief trainer." For the post-course assessment, we used an 18-point checklist that included seven themes that had been previously identified as vitally important for procedures in general.[2] These included procedural competence, preparation, safety, patient communication, infection control, post-procedure care, and teamwork.

After the sessions, the participants were given an opportunity to complete the procedure in its entirety on the mannequin. We found that most of participants were able to hit multiple marks in each theme, including procedural competence with use of ultrasound for IJ and anatomic landmarks for the subclavian approach.

At the end of the week, we found the feedback for the course was extremely positive. As a team, we again revisited the initial concerns regarding possible complications. We felt that we had dedicated a significant proportion of class time to discuss these concerns with the participants. It was concluded that the use of CVC insertion would only be applied in specific situations, only when necessary, and that the utmost care would be taken to prevent complications.

References

[1] Lammers RL, Davenport M, Korley F, et al. Teaching and Assessing Procedural Skills Using Simulation: Metrics and Methodology. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1079–1087.

[2] McKinley RK, Strand J, Ward L, Gray T, Alun-Jones T, Miller H. Checklists for assessment and certification of clinical procedural skills omit essential competencies: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2008;42(4):338–349.