Tracheostomies are a common surgical procedure for long-term airway management that involves creating a permanent connection between the anterior neck and trachea.

Indications include upper airway obstruction, prolonged mechanical ventilation, long-term management of secretions, severe obstructive sleep apnea, and head/neck surgery.1 They are placed inferior to the cricothyroid membrane, most commonly between the second and third tracheal rings.2 They can be performed using either a percutaneous dilational or an open surgical approach. For mechanically ventilated patients, tracheostomy is generally performed between day 7 and 21 of ventilation.3 Complications occur in 40-50% of cases, with life-threatening ones in about 1% of cases. Of these severe complications, mortality approaches 50%.4

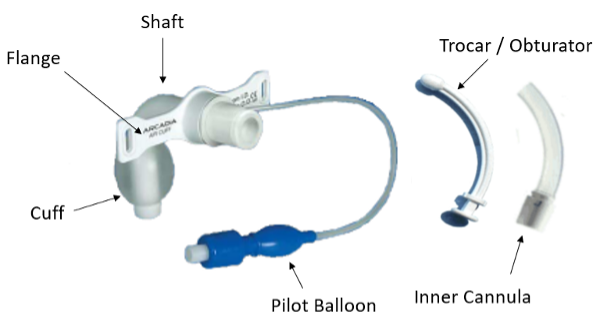

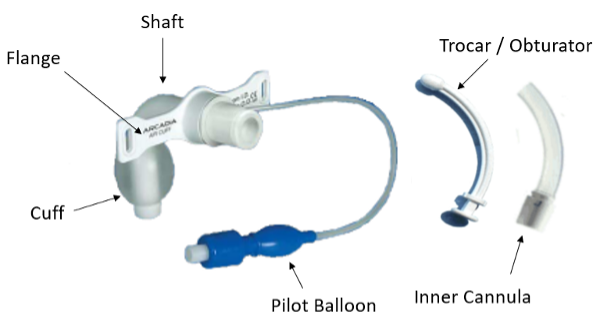

Device Components

Components of a tracheostomy tube5

- Connector/adaptor: connects the tracheostomy tube to the ventilator if needed. May be part of the inner cannula.

- Flange: used to secure the tracheostomy tube to the neck via the two neck strap openings along either side. Typically between the connector and the shaft.

- Shaft: the portion from the connector to the distal tip. Angled to accommodate its position in the proximal neck/trachea. The distal tip is usually tapered for easy insertion.

- Inner cannula: a narrower hollow cannula of the same length and shape as the tracheostomy itself and lies inside the main lumen of the tracheostomy tube. The key advantage is that it can be removed and cleaned regularly without removing the tracheostomy tube from its stoma, so the airway remains intact and stable. Not present in some models.

- Cuff: inflated using a pilot balloon to serve as a one-way valve similar to that on an endotracheal tube. Located just superior to the distal tip. Note that some tracheostomy tubes are cuffless by design.

- Trocar/obturator: a smooth, rounded device with a tapered distal end that aids in placement/replacement of the tracheostomy tube. Remove once the tube is secured.

Must-do actions for every patient

Apply supplemental oxygen to the nose and mouth via non-rebreather and to the tracheostomy stoma via a tracheostomy collar or facemask. When performing bag-valve mask ventilation, occlude the stoma for traditional BMV through the naso-oropharynx, or occlude the nose and mouth if ventilating through the stoma.

First, determine the original indication for the tracheostomy and if the patient has had a laryngectomy. Laryngectomy patients have no connection between the oropharynx and airway and thus cannot be oxygenated or intubated from above. Laryngectomies have a larger stoma and, generally, do not have any devices within them. Then determine when the tracheostomy was placed as those placed less than a week prior should not be replaced at bedside (see explanation below). Lastly, have a low threshold for calling expert airway help (eg, ENT, anesthesia, general surgery) as you work through the following differential.

COMPLICATIONS

Decannulation

- Definition: removal of the tracheostomy tube from the trachea. Decannulation can be complete (tube absent from the stoma) or partial (tube tip embedded in the soft tissue of the neck).

- Risk factors: mental status change, traumatic brain injury, increased secretions, recent tracheostomy change, and increased neck thickness.6 Tracheostomies placed using a percutaneous technique are at higher risk for decannulation than those placed using an open surgical approach.1

- Management

- For tracheostomies placed within the past 7 days, proceed with oral intubation with cuff placement beyond the stoma or facial ambu bag ventilation if intubation is not possible. Decannulation within the first week of placement is more concerning due to the lack of mature stoma formation and a narrow tracheocutaneous tract, increasing the risk of airway loss. As such, do not attempt to replace a tracheostomy tube in the first 7 days as this is at high risk of creating a false tract. For tracheostomies placed > 7 days ago, place a new tracheostomy tube through the stoma, preferably via fiberoptic endoscopy.4

- If replacing the tracheostomy tube, do so as soon as possible as stomas may narrow significantly over hours. If any resistance is met, attempt again with a smaller tube size. If no other tracheostomy tube is available, consider a similarly sized endotracheal tube.

- Following successful recannulation, confirm placement by fiber-optic visualization. Apply low-volume, gentle bag-valve ventilation while setting up continuous capnometry to monitor ventilation.

Obstruction

- Definition: inability to oxygenate or ventilate through the tracheostomy tube. Often due to dried secretions, mucus plugs, clotted blood, or partial tube displacement onto the posterior tracheal wall or into a false lumen.

- Risk factors: small trach tube size, single cannula tracheostomy tube, poor trach care1.

- Management:

- Remove external devices such as speaking valves, obturators, decannulation cap, bandages, or humidifying devices.

- Remove the inner cannula if present.

- Suction through a flexible suction catheter. If the device cannot be passed into the trachea, a complete obstruction is present. Do not use stiff instruments to assess patency as this may create a false lumen7.

- Deflate cuff (if present). This allows for oxygenation/ventilation around the tracheostomy tube since the tube lumen is occluded.

- Remove the tracheostomy tube. Ensure the patient is receiving high-flow oxygen to both the face (naso-oropharynx) and stoma afterwards. When ventilating, close the other opening with gauze.

Hemorrhage

- Definition: If within the first 48 hours of placement, bleeding is often related to operative issues such as accidental vein puncture, suctioning, and infection.8 After 48 hours, the most life-threatening complication is a tracheo-innominate artery (TIAF) fistula, a direct communication between the trachea and innominate artery branch of the aorta. Up to half of these will present with a sentinel bleed, such as tracheostomy site bleeding, hemoptysis, or blood seen with tracheal suctioning. This is most often seen within three weeks of placement.8 As such, even minor bleeds or bleeding that has stopped warrant further evaluation with CT angiogram, fiberoptic tracheal visualization, or operative exploration.

- Risk factors: cuffed tracheostomy tube, low trach placement, high cuff pressure, high-riding innominate artery, excessive neck movement, and tracheostomy infection.9

- Management:

- Overinflate the trach balloon with up to 50 mL of air10

- If the tracheostomy tube is uncuffed, remove it and re-intubate the oropharynx or stoma with an endotracheal tube with a cuff that can be overinflated to 50 mL of air.

- If bleeding is not controlled, insert a finger into the trach stoma for digital compression of the artery anteriorly against the sternum until definitive surgical repair is performed (Utley maneuver). The finger should not be removed until in the OR and directed by the surgeon. If possible, perform oropharyngeal intubation to ventilate the patient.

- Activate surgery, ENT, and/or IR for definitive management

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF)

- Definition: communication between the posterior wall of the trachea and the anterior wall of the esophagus. Often from prolonged pressure from the trach balloon which causes ischemic necrosis and tissue breakdown.11

- Risk factors: high airway pressures, prolonged presence of a cuffed trach tube, steroid use, type 1 diabetes mellitus, chronic hypoxia, poor nutritional status.11

- Presentation: may present as persistent air leaks, abdominal distension (air in the digestive tract), pulmonary aspiration injury, cough with swallowing, copious bronchopulmonary secretions, and respiratory distress.4

- Management: suctioning, discontinue oral feeding, elevate head of bed to 45 degrees. Remove any naso- or oro-gastric tubes to prevent pressure necrosis and worsening of the fistula. If a G-tube is present, drain the contents of the stomach.11

Tracheal Stenosis

- Definition: tracheal narrowing due to fibrosis of peristomal and tracheal tissues, with symptoms not developing until the tracheal lumen is reduced by more than 50%.12

- Risk factors: trauma to the trachea from injury during the procedure itself, ischemia from balloon overinflation, infection, GERD, obesity, and hypotension.12

- Presentation: difficulty clearing secretions, cough, and exertional dyspnea. Often presents within 2 months of decannulation.1

- Management: less of a role in the ED. Can be treated with dilation, excision with end-to-end anastomosis, or laser excision of fibrous tissue.4

Infection

- Common early infections include mild cellulitis at the stoma site and tracheitis, more often after tracheostomies performed by the open surgical approach versus the percutaneous tracheostomy approach. These cases can be managed with regular cleaning of the stoma site, tracheal suctioning, and appropriate daily dressing changes. Antibiotics are not generally needed.10

- More severe but less common infections that require antibiotics are stoma abscess formation, mediastinitis, necrotizing fasciitis, or osteomyelitis/septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint.4

- In general, the presence of trach tubes disrupts swallowing which can increase the risk of aspiration. This is especially true with cuffed tubes which can compress the esophagus. Aspiration of secretions can lead to pneumonia or lung abscesses.12

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Have a stepwise approach for tracheostomy patients who present to the ED. Consider the life-threatening complications such as decannulation, obstruction, and hemorrhage, which are rare but require immediate intervention. Subacute complications such as tracheoesophageal fistula formation, tracheal stenosis, and infections may also occur.

- If a tracheostomy becomes dislodged within 7 days of placement, do not replace the tracheostomy. Instead, intubate from the oropharynx.

- Familiarize yourself with the tracheostomy tube components and what equipment is available for troubleshooting in your ED.

- While working through the differential for tracheostomy patients, always apply supplemental oxygen to both the naso-oropharynx and stoma and consider when the tracheostomy was placed and the patency of the upper airway.

- If available, consider early consult with ENT, Surgery, or Pulmonary to assist with troubleshooting.

REFERENCES

- Fernandez-Bussy S, Mahajan B, Folch E, Caviedes I, Guerrero J, Majid A. Tracheostomy tube placement: early and late complications. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2015; 22(4):357-364.

- Cipriano A, Mao ML, Hon HH, et al. An overview of complications associated with open and percutaneous tracheostomy procedures. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2015;5(3):179-188.

- Hyzy R, McSparron J. Tracheostomy: Rationale, indications, and contraindications. UpToDate. Retrieved June, 14, 2022.

- Bontempo LJ, Manning SL. Tracheostomy Emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019;37(1):109-119.

- National Tracheostomy Safety Project Manual 2013. Tracheostomies & Laryngectomies. (2022). Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- Goldenberg D, Ari EG, Golz A, et al. Tracheotomy complications: a retrospective study of 1130 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000; 123(4):495-500.

- McGrath B, Bates L, Atkinson D, Moore JA, National Tracheostomy Safety Project. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia. 2012; 67(9):1025-1041.

- Bradley P. Bleeding around a tracheostomy wound: what to consider and what to do? J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123(9):952-956.

- Wang RC, Perlman PW, Parnes SM. Near-fatal complications of tracheotomy infections and their prevention. Head Neck. 1989;11(6):528-533.

- Hyzy R, McSparron J. Tracheostomy: Postoperative care, maintenance, and complications in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- Pool C, Goyal N. Operative management of catastrophic bleeding in the head and neck. Head Neck. [Online] 28 (4), 220–228.

- Epstein SK. Late complications of tracheostomy. Respir Care. 2005;50(4):542-549.