A 69-year-old female with a history of hypertension and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) presents to the emergency department (ED) with syncope, altered mental status, and chest pain. A family member heard a thump in an adjacent room and discovered her unresponsive on the floor. Upon EMS arrival, she is initially hypotensive with systolic blood pressure around 70 mmHg that responds to fluids en route. Initial ED vitals show HR 58, RR 24, BP 110/37, T 37.5. She is somnolent but able to awaken, answer questions, and follow commands. An inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is confirmed on ECG. Given her unusual constitution of signs and symptoms a point-of-care ultrasound is performed to further investigate.

A type A aortic dissection is quickly confirmed with a bedside echocardiogram, displaying a dilated aortic root with dissection flap extending proximally and distally with severe aortic insufficiency. CT surgery and cardiology are urgently consulted, and the patient is taken directly to the operating room for definitive repair.

Background

Thoracic aortic dissection is an uncommon though catastrophic condition that classically presents with chest pain and hemodynamic compromise. The pathophysiology involves a tear in the aortic intima, usually proceeding degeneration of the aortic media. A false lumen is created that may extend proximally, distally, or both, as blood passes into the aortic media through the tear. Rupture of the dissection into the pericardium, dissection into the aortic valvular annulus, coronary artery dissection leading to acute myocardial infarction, or organ failure due to abdominal aortic branch obstruction usually result in death.

Risk factors for aortic dissection include hypertension, collagen disorders, pre-existing aortic aneurysm, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic instrumentation or surgery, coarctation of the aorta, and pregnancy.

Several different classification systems have been used to describe aortic dissections; however, the Stanford classification is the one most frequently used by emergency physicians. A thoracic aortic dissection is labeled a Stanford type A dissection if there is any involvement of the ascending aorta, or a Stanford type B if the dissection is restricted to the descending aorta.

Signs and symptoms are dependent on the extent and location of dissection and can include chest or back pain, hypertension or hypotension, peripheral pulse deficit, new murmur, focal neurologic deficit, and syncope. Mental status changes and hypotension are much more likely to occur in a type A dissection.

Diagnosis

While type B aortic dissections are classically managed medically, type A dissections are considered a surgical emergency, with mortality rapidly increasing 1-2% per hour for the first 48 hours — leading to a 50% mortality rate after 48 hours.1 Therefore, rapid diagnosis is paramount. CT angiography is the gold standard and most utilized imaging modality. In an unstable patient, however, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is recommended at bedside. (See The UtiliTEE of Ultrasound in Cardiac Arrest. EM Resident. 2016;43(5):16-17.) This of course is not without its downsides, including the need for procedural sedation during a potentially tenuous clinical condition as well as the availability of the specialized equipment and staff necessary to perform the procedure.

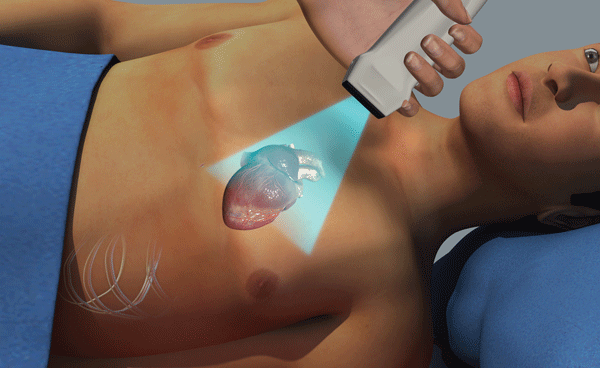

Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is a valuable and underutilized bedside tool that can provide immediate information in patients presenting with suspected aortic dissection. It is safe, portable, rapid, and readily available, making it an ideal screening tool to evaluate for the presence or absence of features that need timely and definitive intervention. TTE is especially useful in identifying pericardial effusion from proximal dissection, severe aortic root dilatation, regional wall motion abnormality, aortic regurgitation, or intimal aortic flap.

TTE images of the ascending aorta may detect an intimal flap that would appear as a hyperechoic linear structure within aortic lumen that moves with each heartbeat (Figure 1). Ascending aortic images can be obtained in parasternal long axis (PSLA) and suprasternal notch (SSN) views (Figures 2,3). Despite a low sensitivity, TTE carries a high specificity for ruling in the diagnosis.

One commonly used measurement that helps stratify a patient's risk for aortic dissection in the case that the intimal flap is not detected is the aortic root measurement (Figure 4). Patients with thoracic aortic root aneurysms carry a much higher risk for dissection. The parasternal long axis is the preferred view for aortic root measurement and generally correlates with measurements on CTA. The aortic root should be measured from outside wall to inside wall at it's the widest point visible during diastole, usually across the sinuses of Valsalva. Measurements less than 4 cm are considered normal, 4.0 to 4.5 cm borderline, and greater than 4.5 cm aneurysmal.2

The Evidence

The sensitivity of TTE is higher in proximal (versus distal) aortic dissections, which are generally the most emergent, high-risk cases and therefore the ones in need of a prompt bedside imaging modality.3 A recent retrospective study including 178 patients referred to cardiac surgery for type A dissection showed that TTE was an equally reliable method for measuring the aortic arch when compared to CT for diagnosis, with the advantage of providing other clinically important information including cardiac tamponade, severe aortic dilatation, and aortic regurgitation.4

Unfortunately, despite a high number of case reports in the literature citing anecdotal diagnosis of dissection with point-of-care TTE, few high-quality studies within the emergency department population currently exist.5,6 The increasing number of emergency medicine physicians trained in point of care ultrasound, combined with its increased availability as a diagnostic modality, makes this an area ripe for future exploration and research.

Bottom Line

While TTE does not replace TEE, CT, or MR angiography, it is a safe and effective early adjunct for timely diagnosis and management of acute aortic dissection.

References

- Meredith L, Masani N. Echocardiography in the emergency assessment of acute aortic syndromes. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(1):i31-39.

- Kennedy Hall M, Coffey EC, Herbst M, et al. The “5Es” of emergency physician-performed focused cardiac ultrasound: a protocol for rapid identification of effusion, ejection, equality, exit, and entrance. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(5):583-593.

- Barman M. Acute Aortic Dissection. e-journal of Cardiology Practice. 2014;12(25). https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines-&-Education/Journals-and-publications/ESC-journals-family/E-journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-12/Acute-aortic-dissection

- Sobczyk D, Nycz K. Feasibility and accuracy of beside transthoracic echocardiography in diagnosis of acute proximal aortic dissection. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2015;13:15.

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et all. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease; a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiology, Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation. 2010;121(13):e266.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Aortic Dissection, Diercks DB, Promes SB, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients with Suspected Acute Nontraumatic Thoracic Aortic Dissection. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(1).