A 2015 study showed that when patients with opioid use disorder were started on buprenorphine with a behavioral intervention in the ED, they were 80% more likely to remain in treatment at 30 days.

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old male presents to the ED, triaged as “social work.” Vital signs are within normal limits. When you walk into the room you see an uncomfortable appearing man with the blankets pulled over his head. He is complaining of stomach cramps and that he “feels sick.” On exam, you notice gooseflesh, rhinorrhea, and dilated pupils. He states he has hit “rock bottom” and wants help. He reports he last used heroin yesterday morning and has been using 10 bags daily for the past 2 weeks. Before that, he was in a recovery house, where he was opioid-free for 1 month. The patient asks if there is anything you can do to help him quit heroin for good.

In addition to connecting this patient to treatment resources for his opioid use, what can you do to help this patient while they are in the ED under your care? What should physicians know about this patient population?

Epidemiology

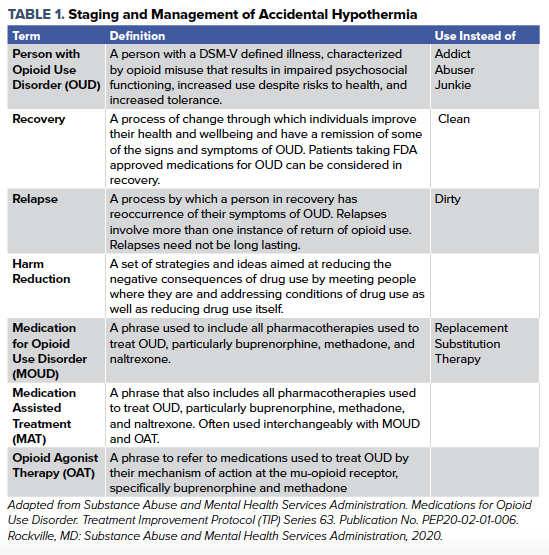

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) as a chronic treatable illness characterized by opioid misuse, impaired social functioning, risky use, and opioid tolerance.1 The language around OUD has evolved over the last several years to be less stigmatizing towards patients and more precise in describing diseases and treatments. Commonly used terminology is included in Table 1. An estimated 2.2 million Americans suffer from OUD, the majority related to prescription opioid misuse, although a significant proportion have heroin and fentanyl related OUD.1 Opioid overdose resulted in more than 46,000 deaths in 2018, exceeding the number of fatalities from motor vehicle collisions.1 Because people with OUD are often socioeconomically disadvantaged and may lack the resources to maintain a primary care provider, and the episodic nature of relapses, many people with OUD will present to the emergency departments as a primary source of health care. Every ED visit by a person with OUD represents a chance to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. One study estimated that after an ED visit for nonfatal opioid overdose, the 1-month mortality risk was 1.1% and the 1-year mortality was as high as 5.5%.2 There has been an increased recognition within EM that starting a medication for OUD can improve survival in these patients. In fact, a 2015 study showed that when patients with OUD were started on buprenorphine with a behavioral intervention in the ED, they were 80% more likely to remain in treatment at 30 days, compared to behavioral intervention or referral to treatment alone.3 It is important that ED physicians know how to use these medications in properly selected patients. This article will focus primarily on buprenorphine, which, although not the only medication for OUD, is one of the most accessible and easiest to initiate for an ED patient population.

Opioid Withdrawal Signs and Symptoms

Opioid withdrawal first begins with opioid dependence. Frequent exposure to opioid agonists will lead to opioid tolerance and neurobiological changes at the mu-opioid receptor.1 As patients become more tolerant of opioids they no longer have the same clinical response at the same dose and will need higher doses to achieve the same response.4 A subset of patients who develop tolerance will become dependent on opioids, meaning that they will go through withdrawal symptoms if they stop using the drug.4 Opioid addiction is further defined by aberrant behaviors and increased use despite negative health consequences, and is a chronic and often relapsing disorder.4 Cessation of agonist activity at the opioid receptor leads to the clinical syndrome of opioid withdrawal.1 One way to evaluate for opioid withdrawal is the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS), which is a score from 0-36 based on a combination of subjective and objective findings.1,5 Tachycardia, piloerection, mydriasis, myalgias, GI distress, and restlessness are all key findings that contribute to a high score.5 Generally, scores greater than 8-12 are used to define withdrawal for the purpose of buprenorphine administration.5

Treatment with Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu-opioid receptor, meaning that at low doses it will act in many ways like a full agonist with some analgesic and decreased craving effect.1 At high doses it has a ceiling effect and, although it has a very high affinity for the mu-opioid receptor, it does not cause the respiratory depression and euphoria that full agonists do.4 Buprenorphine has the highest affinity for the mu-opioid receptor, and will thus displace other agonists from the receptor. This is important as it can precipitate opioid withdrawal by displacing the full agonist from the receptor if taken too close in time to a full agonist.5,6 It also suggests that a patient on buprenorphine will require higher doses of a full agonist such as fentanyl, if you are treating an acutely painful condition like a fracture and need to provide analgesia. Preparations of buprenorphine often include naloxone (brand name Suboxone), an opioid receptor antagonist. Naloxone undergoes extensive 1st pass metabolism and has low bioavailability when taken by mouth.6 It is included in buprenorphine preparations in order to deter IV misuse of prescribed buprenorphine. Protocols have been developed for initiating buprenorphine in the ED. Most protocols call for starting buprenorphine when the COWS score is greater than 8 to avoid precipitated withdrawal, although a more conservative approach might wait until COWS >12.5,6 Patients taking short-acting oral opioids, heroin, or fentanyl will typically require 6-12 hours since last use, longer acting oral opioids will require 12-24 hours and methadone will require >72 hours since last use before buprenorphine can be started without precipitating withdrawal.5,6 Additionally, most protocols call for starting with either a 4mg or 8mg sublingual (SL) buprenorphine dose and observing the patient for 30-60 minutes for resolution of withdrawal symptoms.3,5,6 If symptoms persist, another dose of buprenorphine can be administered. At doses of 8 mg to 16 mg of SL buprenorphine a patient’s mu-opioid receptors will be almost entirely saturated, and this dose should treat withdrawal symptoms in most OUD patients if taken once daily.1,3,6 The most common adverse reaction to buprenorphine is nausea.1 Although higher doses are likely safe, there is concern for respiratory depression particularly if co-ingested with other medications that are respiratory depressants such as benzodiazepines. If a patient is not in withdrawal but wishes to initiate buprenorphine, home initiation can be considered.1 Patients who are initiated on buprenorphine should be referred to an outpatient prescriber of buprenorphine. Rapid follow up with an outpatient provider is important, and warm handoffs (i.e. face to face discussions with outpatient providers) or bridge clinics out of the ED can be ways of ensuring continuity of care in a patient population that historically has faced many hurdles to accessing healthcare.5,6 A peer recovery specialist, if available, can provide guidance and help engage the patient in treatment.7 A peer recovery specialist is someone who is in remission and trained to mentor and advocate for patients with substance use disorder.7 Through their shared lived experience they can provide effective support for patients who may struggle to navigate in a complex medical system, and peer recovery specialists have been shown to improve engagement in therapy and reduce use of substances.7 ED physicians who have obtained a DEA X-waiver can prescribe sufficient days of buprenorphine until the next outpatient appointment; however, even non X-waivered physicians can initiate buprenorphine and have patients return to the ED for up to 3 consecutive days to receive doses of buprenorphine.

Special Considerations

Concomitant Substance Use Disorders (SUD)

Patients should be counseled about the risk of respiratory depression if using other substances like benzodiazepines; however. other SUDs are not an absolute contraindication to buprenorphine. Overdose and respiratory depression from concomitant substance use is far more likely to be seen in untreated OUD than in a patient on buprenorphine.1

Chronic Pain

Buprenorphine has an analgesic effect, although it is shorter than its effect on reducing craving in OUD. BID or TID dosing is sometimes employed in patients with chronic pain who also need treatment for OUD.1,6 Treatment of acute pain in patients with OUD on buprenorphine is beyond the scope of this article, but, briefly: full opioid agonists can be used, however, this should be a shared decision with the patient, and consultation with an acute pain service should be considered.

Diversion

Diversion of buprenorphine is a concern of some clinicians, likely due to the concern of prescribing a multiple day course of an opioid receptor agonist to someone with a substance use disorder and reports of buprenorphine having a street value. Surveys of patients with opioid use disorder do show that patients will use diverted buprenorphine.8 However, studies have shown that diverted buprenorphine is most often used to treat withdrawal symptoms.8 As noted above, because of the pharmacologic properties of buprenorphine, it is less likely to cause respiratory depression than other opioids and thus diversion should be considered an acceptable risk.

Pregnancy

There is theoretical concern that the naloxone present in many buprenorphine formulations may precipitate neonatal abstinence syndrome, and it has been recommended that pregnant women should use the buprenorphine monoproduct.1,5

Harm Reduction

Not all patients with OUD will be ready to start MOUD and/or participate in psychosocial-based therapy. It is important to help patients with OUD reduce the morbidity and mortality from opioid misuse even if they aren’t ready to stop misusing opioids, just as we would want a patient with diabetes to prevent a lower extremity amputation even if they aren’t compliant with a low carbohydrate diet. Harm Reduction is a set of techniques and strategies to reduce the negative health consequences of drug use, such as skin and soft tissue infections, hepatitis C, and opioid overdose.6 For patients that use IV opioids there may be barriers to safe injection drug use such as fear of arrest because they are carrying drug paraphernalia or lack of access to clean water. If there are syringe exchange services in your community, they can provide resources for safer injection drug use. Because of an increase in high potency opioids in the drug supply, like fentanyl, it is important to advise patients to not use alone, or to do a tester shot, in order to decrease the risk of overdose. Fentanyl testing strips, if available, can also be used to identify fentanyl in the drug supply so that patients with OUD can take the appropriate precautions. Finally, naloxone should be prescribed and made widely available for patients with OUD or for all patients in communities with high rates of OUD. Although prescribing naloxone is a logical intervention to reduce overdose death, one study found that of patients with an ICD-10 diagnosis of opioid misuse, dependence, or overdose, only 4.6% of insured patients received a prescription for naloxone.9

- Summary

Many patients with OUD will visit your emergency department. These patients have a chronic illness that carries serious morbidity and mortality. For patients who are interested, buprenorphine is an effective and evidence-based treatment for OUD. - Buprenorphine is safe, and starting a patient on buprenorphine is within the scope of practice of ED physicians. Start 4-8 mg of buprenorphine once daily in patients with OUD who are experiencing withdrawal and ensure prompt follow up with an outpatient provider who can prescribe buprenorphine. Recognize that some patients may need high doses or split doses.

- Some patients will not want to start buprenorphine, but there are still ways to help these patients based on resources that are available in your community for harm reduction. Consider drafting harm reduction discharge instructions.

- Finally, patients with OUD face a lot of stigma in society; they shouldn't have to in an ED. Treat these patients with the respect they deserve.

Case Conclusion

The patient's COWS score is 11. You start the patient on 8 mg buprenorphine. He reports improvement in his cravings and stomach cramps. A peer recovery specialist connects with the patient while still in the ED and makes a plan to accompany the patient to a residential addiction treatment center, with an open bed, during normal business hours. The treatment center will continue his buprenorphine prescription.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63. Publication No. PEP20-02-01-006. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020.

- Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, Schuur JD. One-Year Mortality of Patients After Emergency Department Treatment for Nonfatal Opioid Overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):13-17. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020

- D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3474

- Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid Dependence vs Addiction: A Distinction Without a Difference? Arch Intern Med.2012;172(17):1342–1343. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3212

- Herring AA, Perrone J, Nelson LS. Managing Opioid Withdrawal in the Emergency Department With Buprenorphine. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(5):481-487. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.032

- AAEM EM Pain and Procedural Sedation Interest Group. Management of Opioid Use Disorder in the Emergency Department: A White Paper Prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Published 9/22/2019. https://www.aaem.org/UserFiles/file/AAEMOUDWhitePaperManuscript.pdf

- Cos TA, LaPollo AB, Aussendorf M, Williams JM, Malayter K, Festinger DS. Do Peer Recovery Specialists Improve Outcomes for Individuals with Substance Use Disorder in an Integrative Primary Care Setting? A Program Evaluation [published online ahead of print, 2019 Sep 13]. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;10.1007/s10880-019-09661-z. doi:10.1007/s10880-019-09661-z

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Chilcoat HD. Understanding the use of diverted buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;193:117-123. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.007

- Follman S, Arora VM, Lyttle C, Moore PQ, Pho MT. Naloxone Prescriptions Among Commercially Insured Individuals at High Risk of Opioid Overdose. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193209. Published 2019 May 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3209