Although spider bite is a common complaint in the ED, systemic loxoscelism is a rare and deadly consequence of undiagnosed brown recluse bites. Use the NOT RECLUSE mnemonic to keep from missing it.

A 20-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with a painful ulcer to her proximal thigh that she says has grown in size and become necrotic over the past 3 days. She also reports fever, malaise, and dark urine for the past day. She has been helping her parents renovate their old house in the countryside and believes she may have been bitten by a spider.

"Is this a spider bite?"

The ED chief complaint of spider bite is a common one, and as most residents will realize, the majority (as high as 84% in one study) of these will have a final diagnosis of a skin and soft tissue infection like abscess or cellulitis.1 Even in actual cases of spider bites, the spider will rarely be available for definitive identification, so the treating physician must be aware at least of the clinical presentation of the two most common venomous spiders in North America: those of the genus Loxosceles and Lactrodectus, frequently referred to as brown recluses and black widows, though there are other relevant species within each genus. In this article, we will cover Loxosceles specifically, but would encourage readers to familiarize themselves with Lactrodectus as well.

The Elusive Recluse

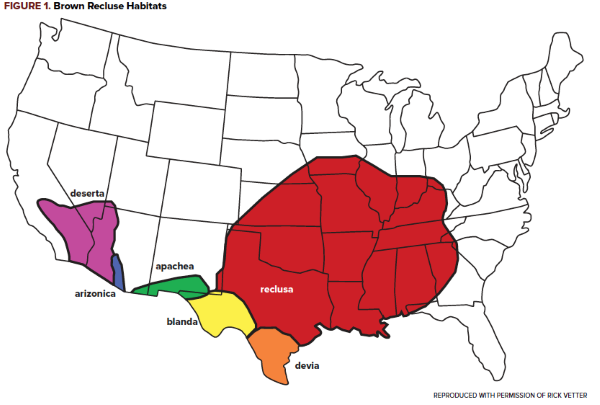

Loxosceles spiders are found in certain endemic areas in North and South America, especially the South, Southeast, and Southwest United States (Figure 1).

Location in an endemic area is a strong predictor of a spider belonging to the Loxosceles genus, as these spiders are rare outside of these described regions.2,3 These spiders are nocturnal hunters who are not aggressive but will bite if threatened, typically found inside homes in dark, quiet areas such as basements and attics. Outside, they can be commonly found underneath rocks and the bark of dead trees. They have 6 eyes arranged in dyads, while most other spiders have 8, and the markings on their torso are said to resemble a violin or fiddle, though the markings are less reliable and have led to the misidentification of harmless spiders in non-endemic areas as brown recluses.

While definitive epidemiological data is lacking due to the difficulty in confirming a bite, retrospective data of 359 patients over 11 years from Brazil, where Loxosceles envenomation is a significant public health concern,4 demonstrates bites in children and adults up to 59 years of age, with males and females equally represented, and the most common sites of injuries being the thigh and the trunk.5 A similar study from Chile demonstrated that 73.6% of bites occurred during the summer months of the year.6

Local Toxicity

The stereotypical cutaneous lesion in Loxosceles bites is characterized by central necrosis, a middle ring of blanched skin, and an outer ring of surrounding erythema. This pattern is known as the “red, white, and blue” lesion and is highly suggestive of envenomation. The likely pathophysiology for this necrosis involves the cytotoxic effects of sphingomyelinase D found in Loxosceles venom.7

Over the 14 days following the bite, an eschar will develop over the site and then slough off spontaneously. The rate of healing past these first 2 weeks often depends on the location and size of the wound, but most patients recover from the cutaneous effects of envenomation and do not progress to systemic toxicity.

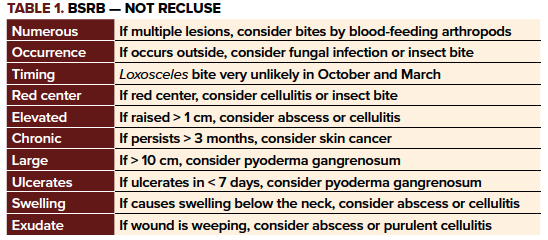

As mentioned previously, appropriate identification of an offending spider is unlikely to be of much use to ED physicians treating patients with possible spider bites. Because the differential for a necrotic wound is large and the diagnosis is often a clinical one, dermatologists and entomologists have published a memory aid for when to consider a diagnosis other than brown recluse spider bite (BRSB): NOT RECLUSE (Table 1).8

Systemic Illness

In addition to localized necrosis, some patients will develop systemic effects of Loxosceles envenomation, collectively referred to as "loxoscelism." The most well-described elements of loxoscelism include fever and chills, nausea and vomiting, arthralgias, intravascular hemolysis with hemoglobinuria, rhabdomyolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and acute kidney injury.9 Sphingomyelinase D has also been implicated in systemic loxoscelism, damaging the erythrocyte cell membrane and recruiting inflammatory mediators leading to a systemic inflammatory reaction.10

Again due to the difficulty of confirming cases of BRSB, the true rate of loxoscelism is unknown; while it appears to be rare in North America, the condition is potentially life-threatening and can affect otherwise healthy individuals,7 so it must be on the differential when appropriate. In particular there are reports of children developing severe systemic loxoscelism prior to the appearance of the classic skin findings.11,12 While there are lab tests that can differentiate Loxosceles bites from the necrotic wounds of several other spider species, these tests are not readily available to most ED physicians.13 Instead the best way to diagnose loxoscelism is to be aware of and monitor for the feared systemic complications themselves.

ED physicians should turn their attention initially toward the airway, breathing, circulation, and mental status of the patient. Once any needed resuscitation is complete and the patient is determined to be at risk for loxoscelism, relevant labs include serum creatinine, hemoglobin/hematocrit, platelets, Coombs test, prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, D-dimer, fibrinogen, and creatine kinase, with additional testing dictated by the patient’s presentation. Urinalysis is also indicated, as hematuria is an ominous predictor of intravascular hemolysis.

Patients with diagnostic testing concerning for loxoscelism, including hematuria, should be admitted to the hospital and closely monitored, likely in the ICU.14 Severe hemolysis should be transfused as necessary, and coagulopathy/DIC may need to be reversed in the setting of life-threatening bleeding. Those experiencing rhabdomyolysis, hemoglobinuria, or acute kidney injury require intravenous fluid hydration.5 Antivenom is currently not available in the United States, so treatment is aimed at supportive care of the complications as they arrive.

Case Conclusion

In the setting of a necrotic lesion concerning for BRSB, the ED team identified the dark urine as concerning for hemoglobinuria from loxoscelism. Urinalysis was positive for blood, confirming suspicion for hemoglobinuria and intravascular hemolysis. The patient’s hematocrit was 35%, platelets were 163,000/mcL, her Coombs test was positive, and her creatine kinase, PT, PTT, D dimer, and fibrinogen were within normal limits. She was admitted to the medical ICU and although she required a single transfusion of packed red blood cells during her admission, she recovered over the next 5 days and was discharged home with wound care for her necrotic ulcer.

Take-Home Points

- The diagnosis of BRSB is a clinical one, as spider identification is often not possible and definitive lab testing is not widely available.

- BRSB are extremely uncommon outside of endemic areas.

- Using the NOT RECLUSE mnemonic, consider a broad differential diagnosis.

- Systemic loxoscelism is rare but deadly – screen suspected patients for hemolysis, rhabdomyolysis, and acute kidney injury.

- As antivenom is unavailable in the United States, treatment for systemic loxoscelism is ICU admission and supportive care.

References

- Suchard JR. “Spider bite” lesions are usually diagnosed as skin and soft-tissue infections. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:473–481.

- Vetter RS. Arachnids submitted as suspected brown recluse spiders (Araneae: Sicariidae): Loxosceles spiders are virtually restricted to their known distributions but are perceived to exist throughout the United States. J Med Entomol. 2005;42(4): 512–521.

- Rhoads J. Epidemiology of the brown recluse spider bite. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(2):79-85.

- Chippaux JP. Epidemiology of envenomations by terrestrial venomous animals in Brazil based on case reporting: from obvious facts to contingencies. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:13.

- Malaque CM, Castro-Valencia JE, Costa Cardoso JL, de Siqueira Francca FO, Barbaro KC, Fan HW. Clinical and epidemiological features of definitive and presumed loxoscelism in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2002;44:139–143.

- Schenone H, Saavedra T, Rojas A, Villarroel F. Loxoscelism in Chile. Epidemiologic, clinical and experimental studies. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1989;31:403–415

- Sams HH, Dunnick CA, Smith ML, King LE. Necrotic arachnidism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(4):561-576.

- Stoecker WV, Vetter RS, Dyer JA. NOT RECLUSE – a mnenmonic device to avoid false diagnosis of brown recluse spider bites. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153: 377-378.

- Repplinger DJ, Hahn I. Arthropods. In: Nelson LS, Howland M, Lewin NA, Smith SW, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RS. eds. Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies, 11e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Kurpiewski G, Forrester LJ, Barrett JT, Campbell BJ. Platelet aggregation and sphingomyelinase D activity of a purified toxin from the venom of Loxosceles reclusa. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;678:467–476.

- Said A, Hmiel P et al. Successful use of plasma exchange for profound hemolysis in a child with loxoscelism. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1464-7.

- Futrell JM. Loxoscelism. Am J Med Sc 1992;304(4):261.

- Stoecker WV, Green JA, Gomez HF. Diagnosis of loxoscelism in a child confirmed with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and noninvasive tissue sampling. J Am Acad Dermatol.2006;55(5):888–890

- Gehrie EA, Nian H, Young PP. Brown recluse spider bite mediated hemolysis: clinical features, a possible role f or complement inhibitor therapy, and reduced RBC surface glycophorin A as a potential biomarker of venom exposure. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76558.